A team of researchers at UC Santa Barbara and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution investigated this previously neglected area of oceanography for signs of an overlooked global cycle. They also tested how its existence might impact the ocean's response to oil spills.

"We demonstrated that there is a massive and rapid hydrocarbon cycle that occurs in the ocean, and that it is distinct from the ocean's capacity to respond to petroleum input," said Professor David Valentine(link is external), who holds the Norris Presidential Chair in the Department of Earth Science at UCSB. The research, led by his graduate students Eleanor Arrington(link is external) and Connor Love(link is external), appears in Nature Microbiology(link is external).

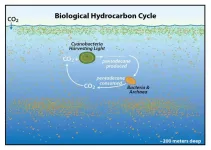

In 2015, an international team led by scientists at the University of Cambridge published a study demonstrating that the hydrocarbon pentadecane was produced by marine cyanobacteria in laboratory cultures. The researchers extrapolated that this compound might be important in the ocean. The molecule appears to relieve stress in curved membranes, so it's found in things like chloroplasts, wherein tightly packed membranes require extreme curvature, Valentine explained. Certain cyanobacteria still synthesize the compound, while other ocean microbes readily consume it for energy.

Valentine authored a two-page commentary on the paper, along with Chris Reddy from Woods Hole, and decided to pursue the topic further with Arrington and Love. They visited the Gulf of Mexico in 2015, then the west Atlantic in 2017, to collect samples and run experiments.

The team sampled seawater from a nutrient-poor region of the Atlantic known as the Sargasso Sea, named for the floating sargassum seaweed swept in from the Gulf of Mexico. This is beautiful, clear, blue water with Bermuda smack in the middle, Valentine said.

Obtaining the samples was apparently a rather tricky endeavor. Because pentadecane is a common hydrocarbon in diesel fuel, the team had to take extra precautions to avoid contamination from the ship itself. They had the captain turn the ship into the wind so the exhaust wouldn't taint the samples and they analyzed the chemical signature of the diesel to ensure it wasn't the source of any pentadecane they found.

What's more, no one could smoke, cook or paint on deck while the researchers were collecting seawater. "That was a big deal," Valentine said, "I don't know if you've ever been on a ship for an extended period of time, but you paint every day. It's like the Golden Gate Bridge: You start at one end and by the time you get to the other end it's time to start over."

The precautions worked, and the team recovered pristine seawater samples. "Standing in front of the gas chromatograph in Woods Hole after the 2017 expedition, it was clear the samples were clean with no sign of diesel," said co-lead author Love. "Pentadecane was unmistakable and was already showing clear oceanographic patterns even in the first couple of samples that [we] ran."

Due to their vast numbers in the world's ocean, Love continued, "just two types of marine cyanobacteria are adding up to 500 times more hydrocarbons to the ocean per year than the sum of all other types of petroleum inputs to the ocean, including natural oil seeps, oil spills, fuel dumping and run-off from land." These microbes collectively produce 300-600 million metric tons of pentadecane per year, an amount that dwarfs the 1.3 million metric tons of hydrocarbons released from all other sources.

While these quantities are impressive, they're a bit misleading. The authors point out that the pentadecane cycle spans 40% or more of the Earth's surface, and more than one trillion quadrillion pentadecane-laden cyanobacterial cells are suspended in the sunlit region of the world's ocean. However, the life cycle of those cells is typically less than two days. As a result, the researchers estimate that the ocean contains only around 2 million metric tons of pentadecane at any given time.

It's a fast spinning wheel, Valentine explained, so the actual amount present at any point in time is not particularly large. "Every two days you produce and consume all the pentadecane in the ocean," he said.

In the future, the researchers hope to link microbes' genomics to their physiology and ecology. The team already has genome sequences for dozens of organisms that multiplied to consume the pentadecane in their samples. "The amount of information that's there is incredible," said Valentine, "and I think reveals just how much we don't know about the ecology of a lot of hydrocarbon-consuming organisms."

Having confirmed the existence and magnitude of this biohydrocarbon cycle, the team sought to tackle the question of whether its presence might prime the ocean to break down spilled petroleum. The key question, Arrington explained, is whether these abundant pentadecane-consuming microorganisms serve as an asset during oil spill cleanups. To investigate this, they added pentane -- a petroleum hydrocarbon similar to pentadecane -- to seawater sampled at various distances from natural oil seeps in the Gulf of Mexico.

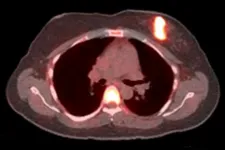

They measured the overall respiration in each sample to see how long it took pentane-eating microbes to multiply. The researchers hypothesized that, if the pentadecane cycle truly primed microbes to consume other hydrocarbons as well, then all the samples should develop blooms at similar rates.

But this was not the case. Samples from near the oil seeps quickly developed blooms. "Within about a week of adding pentane, we saw an abundant population develop," Valentine said. "And that gets slower and slower the further away you get, until, when you're out in the North Atlantic, you can wait months and never see a bloom." In fact, Arrington had to stay behind after the expedition at the facility in Woods Hole, Massachusetts to continue the experiment on the samples from the Atlantic because those blooms took so long to appear.

Interestingly, the team also found evidence that microbes belonging to another domain of life, Archaea, may also play a role in the pentadecane cycle. "We learned that a group of mysterious, globally abundant microbes -- which have yet to be domesticated in the laboratory -- may be fueled by pentadecane in the surface ocean," said co-lead author Arrington.

The results beg the question why the presence of an enormous pentadecane cycle appeared to have no effect on the breakdown of the petrochemical pentane. "Oil is different from pentadecane," Valentine said, "and you need to understand what the differences are, and what compounds actually make up oil, to understand how the ocean's microbes are going to respond to it."

Ultimately, the genes commonly used by microbes to consume the pentane are different than those used for pentadecane. "A microbe living in the clear waters offshore Bermuda is much less likely to encounter the petrochemical pentane compared to pentadecane produced by cyanobacteria, and therefore is less likely to carry the genes for pentane consumption," said Arrington.

Loads of different microbial species can consume pentadecane, but this doesn't imply that they can also consume other hydrocarbons, Valentine continued, especially given the diversity of hydrocarbon structures that exist in petroleum. There are less than a dozen common hydrocarbons that marine organisms produce, including pentadecane and methane. Meanwhile, petroleum comprises tens of thousands of different hydrocarbons. What's more, we are now seeing that organisms able to break down complex petroleum products tend to live in greater abundance near natural oil seeps.

Valentine calls this phenomenon "biogeographic priming" - when the ocean's microbial population is conditioned to a particular energy source in a specific geographic area. "And what we see with this work is a distinction between pentadecane and petroleum," he said, "that is important for understanding how different ocean regions will respond to oil spills."

Nutrient-poor gyres like the Sargasso Sea account for an impressive 40% of the Earth's surface. But, ignoring the land, that still leaves 30% of the planet to explore for other biohydrocarbon cycles. Valentine thinks the processes in regions of higher productivity will be more complex, and perhaps will provide more priming for oil consumption. He also pointed out that nature's blueprint for biological hydrocarbon production holds promise for efforts to develop the next generation of green energy.

INFORMATION: