INFORMATION:

Toward safer steroids: Scientists devise method for improving safety of drug used to treat COVID-19, autoimmune disorders and more

2021-02-02

(Press-News.org) JUPITER, FL - A collaboration led by Scripps Research has developed a way to separate the beneficial anti-inflammatory properties of a group of steroids called glucocorticoids from some of their unwanted side-effects, through an optimization process they named "ligand class analysis."

Their process enabled them to engineer two new, drug-like compounds that show steroidal anti-inflammatory action and other specific traits. One boosts muscle and energy supply, while the other reduces risk of muscle-wasting and bone loss typical of such drugs.

Their report, titled, "Chemical systems biology reveals mechanisms of glucocorticoid receptor signaling," appeared Jan. 28 in the journal Nature Chemical Biology.

Glucocorticoids are steroid hormones, a group that includes cortisone, prednisone and dexamethasone. Among the most frequently prescribed of medications, their anti-inflammatory properties make them useful in an array of forms and doses.

Glucocorticoids are used as injections for hip or back pain, tablets for autoimmune disease, nasal spray for sinus congestion, anti-itch cremes for soothing rashes or insect bites, and more.

Most recently, the glucocorticoid drug dexamethasone has become the standard of care for COVID-19 treatment later in illness, as it can help quiet overaggressive immune attacks in delicate lung tissue and blood vessels.

But glucocorticoids are also among the more problematic of medicines, as prolonged use or high doses can lead to adverse events including high blood pressure, muscle wasting, bone loss, vulnerability to infections, vision problems, anxiety, swelling, weight gain, high blood sugar, insulin resistance, diabetes, and more, while naturally occurring glucocorticoids in the body can contribute to prostate cancer progression.

Pursuing safety

A key goal of the team was to engineer more precise glucocorticoids able to act in tissue-specific or activity-specific way, while limiting specific adverse events, says the study's lead author, Kendall Nettles, PhD, associate professor of Integrative and Structural Biology at the Scripps Research, Florida campus.

"There is a great unmet need to improve glucocorticoids," Nettles says. "We asked, 'Can we develop glucocorticoids that have more selective effects on inflammation and the immune system, instead of hitting the body with a hammer?' This method is showing that we can do that now."

The project pooled the expertise of many collaborators, in areas including chemistry, bioinformatics, structural biology, proteomics, genomics, cell metabolism and more. Contributors included Scripps Research, Florida-based faculty and their scientific staff and students; a researcher from the institute's California-based drug discovery division, Calibr, and scientists from Weill Cornell Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine, the National Cancer Institute and others.

Nettles says their "ligand class analysis" process began with selection of a known corticosteroid compound. Scripps Research chemist Theodore Kamenecka, PhD, modified the compound in many ways to build a collection of new molecules.

One substitution at a time, the scientists created 22 new compounds that showed an ability to actively bind with cell receptors for steroids. They then devised an experimental platform for testing precisely how these compounds affected muscle, bone and lung cells, to indicate each one's risk of causing muscle loss or bone loss, while keeping anti-inflammatory activity.

One of the greatest challenges they encountered was devising a way to accurately test the molecules in cultured cells, Nettles says. At first, they seemed to require 1,000 times more compound than expected to measure impact.

Stress produces results

First author Nelson Bruno had the breakthrough idea of testing only after stress, specifically, fasting followed by brief insulin challenge. That's because stress is the trigger for release of endogenous steroid hormones in real life, Nettles explains.

"It took us two years just to develop the experimental assays to reproduce the effects of what glucocorticoids do in people," Nettles says. "We found we needed realistic physiology."

They also used a machine learning approach to predict how the compounds would affect insulin receptor signaling, gene transcription, protein balance and glucose disposal in the cells, depending on chemical structure.

Through repeated challenges and tests in the cells and in mice, they settled on two compounds, SR11466 and SR16024, as ones with medically useful traits including inflammation control, plus muscle-sparing ability, or mitochondria-building potential. Mitochondria convert cellular nutrients into energy.

The process they developed to refine the compounds has implications well beyond the improvement of glucocorticoids, Nettles adds. It can power more-selective drug-discovery for any number of medicines that work via the cell surface and nuclear receptors to impact signaling and gene transcription in cells, he says.

This project started long before the COVID-19 pandemic began, Nettles says, but it has potential to benefit people sickened with COVID-19. In the context of an infectious disease, the ideal anti-inflammatory would be one that suppressed overly aggressive immune attack without impairing ability to fight off infection, so that's the next goal, he says. More work is needed to address bone loss risk as well, he says.

"These drugs could be used more widely if we could reduce the side-effects profile," Nettles says. "We brought together many recent scientific advances to address a significant problem that affects huge numbers of people. Our findings show that using ligand class analysis, we can potentially improve the safety and specificity of steroids and other needed medicines."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Moffitt researchers identify why CAR T therapy may fail in some lymphoma patients

2021-02-02

TAMPA, Fla. -- Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, or CAR T, has been a breakthrough in the treatment of blood cancers such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Clinical studies have shown overall response rates of more than 80% with an ongoing response of nearly 40% more than two years after therapy. However, the cellular immunotherapy doesn't work for every patient. Moffitt Cancer Center, one of the leading centers for cellular immunotherapy, is researching why some patients have a better CAR T response than others and what can be done to improve the treatment's effectiveness. In a new study ...

Modeling the brain during pain processing

2021-02-02

The many different sensations our bodies experience are accompanied by deeply complex exchanges of information within the brain, and the feeling of pain is no exception. So far, research has shown how pain intensity can be directly related to specific patterns of oscillation in brain activity, which are altered by the activation and deactivation of the 'interneurons' connecting different regions of the brain. However, it remains unclear how the process is affected by 'inhibitory' interneurons, which prevent chemical messages from passing between these regions. Through new research published in EPJ ...

NREL reports sustainability benchmarks for plastics recycling and redesign

2021-02-02

Researchers developing renewable plastics and exploring new processes for plastics upcycling and recycling technologies will now be able to easily baseline their efforts to current manufacturing practices to understand if their efforts will save energy and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Benchmark data calculated and compiled at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) provide a measurement--at the supply chain level--of how much energy is required and the amount of greenhouse gases emitted from the production of a variety of plastics in the United States.

"Today, we employ a predominantly linear economy for many of the materials we use, including plastics," said Gregg Beckham, a senior research fellow at NREL. "Many people ...

Textile sensor patch could detect pressure points for amputees

2021-02-02

A soft, flexible sensor system created with electrically conductive yarns could help map problematic pressure points in the socket of an amputee's prosthetic limb, researchers from North Carolina State University report in a new study.

In IEEE Sensors Journal, researchers from North Carolina State University reported on the lightweight, soft textile-based sensor prototype patch. The device incorporates a lattice of conductive yarns and is connected to a tiny computer. They tested the system on a prosthetic limb and in walking experiments with two human volunteers, finding the system could ...

Hydrogen-producing enzyme protects itself against oxygen

2021-02-02

An international research team from the Photobiotechnology Research Group at Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB) led by Professor Thomas Happe and the Laboratoire de Bioénergétique et Ingénierie des Protéines (CNRS) in Marseille has been able to get to the bottom of this unique feature. They describe the molecular mechanism in Nature Communications on 2 February 2021.

Enzyme repeatedly survives the attack unharmed

Representatives of the [FeFe]-hydrogenase enzyme group combine protons and electrons to form molecular hydrogen at particularly high turnover rates. Some of them even use sunlight as a primary energy source ...

Geisinger-GeneDx research identifies frequent genetic causes of cerebral palsy

2021-02-02

DANVILLE, Pa. and GAITHERSBURG, Md. - Researchers have discovered a strong link between genetic changes known to cause neurodevelopmental disabilities and cerebral palsy.

Cerebral palsy affects movement and posture and often co-occurs with other neurodevelopmental disorders, including intellectual disability, epilepsy and autism spectrum disorder. Individual cases of cerebral palsy are often attributed to birth asphyxia, although recent studies indicate that asphyxia accounts for less than 10% of cases. A growing body of research indicates that cerebral palsy may be caused by genetic changes, ...

New tool facilitates inclusion of people of diverse ancestry in large genetics studies

2021-02-02

BOSTON -- Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have typically excluded diverse and minority individuals in the search for gene variants that confer risk of disease. Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, and other institutions around the world have now developed a free-access software package called Tractor that increases the discovery power of genomics in understudied populations. A study of Tractor's performance and accuracy was published in END ...

Dementia rates higher in men with common genetic disorder haemochromatosis

2021-02-02

New research has found that men who have the Western world's most common genetic disorder are more likely to develop dementia, compared to those without the faulty genes.

Researchers at the University of Exeter and the University of Connecticut have previously found that men with two faulty genes that cause the iron overload condition haemochromatosis are more likely to develop liver cancer, arthritis and frailty, compared to those without the faulty genes.

Now, the team's new analysis of more than 335,000 people of European ancestry in UK Biobank, ...

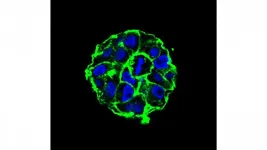

Cancer research expands body's own immune system to kill tumors

2021-02-02

WASHINGTON, February 2, 2021 -- Scientists are hoping advances in cancer research could lead to a day when a patient's own immune system could be used to fight and destroy a wide range of tumors.

Cancer immunotherapy has some remarkable successes, but its effectiveness has been limited to a relatively small handful of cancers. In APL Bioengineering, by AIP Publishing, a team from Stanford University and Genentech describes how advances in engineering models of tumors can greatly expand cancer immunotherapy's effectiveness to a wider range of cancers.

"One of the biggest breakthroughs we've had in cancer research in decades is that we can modify the cells in your own immune system to make them kill cancer cells," said author Joanna Lee.

Using ...

Bile acids may play previously unknown role in Parkinson's

2021-02-02

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich. (Feb. 2, 2021) -- What does bile acid production in the digestive tract have to do with Parkinson's disease?

Quite a lot, according to a sweeping new analysis published in the journal Metabolites. The findings reveal that changes in the gut microbiome -- the rich population of helpful microbes that call the digestive tract home -- may in turn alter bile acid production by favoring synthesis of toxic forms of the acids.

These shifts were seen only in people with Parkinson's and not in healthy controls, a critical difference that suggests bile acids may be a viable biomarker for diagnosing Parkinson's early and tracking its progression. The insights also may provide new avenues for developing therapies ...