(Press-News.org) LOS ANGELES (Feb. 3, 2021) -- For the first time in humans, investigators at Cedars-Sinai have identified the neurons responsible for canceling planned behaviors or actions--a highly adaptive skill that when lost, can lead to unwanted movements.

Known as "stop signal neurons," these neurons are critical in powering someone to stop or abort an action they have already put in process.

"We have all had the experience of sitting at a traffic stop and starting to press the gas pedal but then realizing that the light is still red and quickly pressing the brake again," said Ueli Rutishauser, PhD, professor of Neurosurgery, Neurology and Biomedical Sciences at Cedars-Sinai and senior author of the study published online in the peer-reviewed journal Neuron. "This first-in-human study of its kind identifies the underlying brain process for stopping actions, which remains poorly understood."

The findings, Rutishauser said, reveals that such neurons exist in an area of the brain called the subthalamic nucleus, which is a routine target for treating Parkinson's disease with deep brain stimulation.

Patients with Parkinson's disease, a motor system disorder affecting nearly 1 million people in the U.S., suffer simultaneously from both the inability to move and the inability to control excessive movements. This paradoxical mix of symptoms has long been attributed to disordered function in regions of the brain that regulate the initiation and halting of movements. How this process occurs and what regions of the brain are responsible have remained elusive to define despite years of intensive research.

Now, a clearer understanding has emerged.

Jim Gnadt, PhD, program director for the NIH Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Technologies® (BRAIN) Initiative, which funded this project, explained that this study helps us understand how the human brain is wired to accomplish rapid movements.

"It is equally important for motor systems designed for quick, fast movements to have a 'stop control' available at a moment's notice--like a cognitive change in plan--and also to keep the body still as one begins to think about moving but has yet to do so."

To make their discovery, the Cedars-Sinai research team studied patients with Parkinson's disease who were undergoing brain surgery to implant a deep brain stimulator--a relatively common procedure to treat the condition. Electrodes were lowered into the basal ganglia, the part of the brain responsible for motor control, to precisely target the device while the patients were awake.

The researchers discovered that neurons in one part of the basal ganglia region--the subthalamic nucleus--indicated the need to "stop" an already initiated action. These neurons responded very quickly after the appearance of the stop signal.

"This discovery provides the ability to more accurately target deep brain stimulation electrodes, and in return, target motor function and avoid stop signal neurons," said Adam Mamelak, MD, professor of Neurosurgery and co-first author of the study.

Mamelak notes that many patients with Parkinson's disease have issues with impulsiveness and the inability to stop inappropriate actions. As a next step, Mamelak and the research team will build on this discovery to investigate whether these neurons also play a role in these more cognitive forms of stopping.

"There is strong reason to believe that they do, based on significant literature linking inability to stop to impulsiveness," said Mamelak. "This discovery will enable investigating whether the neurons we discovered are the common mechanisms that link the two phenomena."

Clayton Mosher, PhD, co-first author of the study and a project scientist in the Rutishauser lab, says while it has long been hypothesized that such neurons exist in a particular brain area, such neurons had never been observed "in action" in humans.

"Stop neurons responded very quickly following the onset of the stop cue on the screen, a key requirement to be able to suppress an impending action," said Mosher. "Our result is the first single-neuron demonstration in humans of signals that are likely carried by this particular pathway."

INFORMATION:

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the NIH Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Technologies® (BRAIN) Initiative Awards U01NS098961 and U01NS103792.

DOI: Distinct roles of dorsal and ventral subthalamic neurons in action selection and cancellation

Read more on the Cedars-Sinai Blog: Parkinson's Disease May Begin Before Birth

Contact the Media

NEW YORK and LA JOLLA, CA--A phase 1 clinical trial testing a novel vaccine approach to prevent HIV has produced promising results, IAVI and Scripps Research announced today. The vaccine showed success in stimulating production of rare immune cells needed to start the process of generating antibodies against the fast-mutating virus; the targeted response was detected in 97 percent of participants who received the vaccine.

"This study demonstrates proof of principle for a new vaccine concept for HIV, a concept that could be applied to other pathogens, as well," says William Schief, Ph.D., a professor and immunologist at Scripps Research and executive director of vaccine design at IAVI's Neutralizing Antibody Center, whose laboratory developed the vaccine. "With our many collaborators ...

CHARLOTTE, N.C. - Feb. 3, 2021 - New research on gender inequality indicates that fewer leadership prospects in the workplace apply even to women who show the most promise early on in their academic careers.

Jill Yavorsky, an assistant professor of sociology at UNC Charlotte, co-led the study, "The Under-Utilization of Women's Talent: Academic Achievement and Future Leadership Positions," with Yue Qian, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of British Columbia.

In their paper, published in a leading social science journal, Social Forces, the social scientists discovered that men supervise more individuals ...

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- A study by Mayo Clinic researchers published in Kidney International Reports finds that immune checkpoint inhibitors, may have negative consequences in some patients, including acute kidney inflammation, known as interstitial nephritis. Immune checkpoint inhibitors are used to treat cancer by stimulating the immune system to attack cancerous cells.

"Immune checkpoint inhibitors have improved the prognosis for patients with a wide range of malignancies including melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer and renal cancer," says Sandra Herrmann, M.D., ...

URBANA, Ill. - For decades, kibble has been our go-to diet for dogs. But the dog food marketplace has exploded in recent years, with grain-free, fresh, and now human-grade offerings crowding the shelves. All commercial dog foods must meet standards for complete and balanced nutrition, so how do consumers know what to choose?

A new University of Illinois comparison study shows diets made with human-grade ingredients are not only highly palatable, they're extremely digestible. And that means less poop to scoop. Up to 66% less.

"Based on past research we've conducted I'm not surprised with the results when feeding human-grade compared to an extruded dry diet," says Kelly Swanson, the Kraft Heinz Company Endowed Professor in Human Nutrition in the ...

Like weeds sprouting from cracks in the pavement, cancer often forms in sites of tissue damage. That damage could be an infection, a physical wound, or some type of inflammation. Common examples include stomach cancer caused by H. pylori infection, Barrett's esophagus caused by acid reflux, and even smoking-induced lung cancer.

Exactly how tissue damage colludes with genetic changes to promote cancer isn't fully understood. Most of what scientists know about cancer concerns advanced stages of the disease. That's especially true for cancers such as pancreatic cancer that are usually diagnosed very late.

Researchers ...

Researchers at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) led by Professor Francisco Sánchez-Madrid have found that dendritic cells, which initiate specific immune responses, can reprogram their genes to improve their immune response. The results of the study, funded by Fundación 'la Caixa' and published today in Science Advances, could have important applications in the development of new vaccination and immunotherapy strategies.

Dendritic cells are professional antigen-presenting cells that initiate adaptive or specific immune responses. As described by the research team, "dendritic cells capture possible pathogenic agents in different tissues and entry sites, process their components, and transport them to lymph nodes. Here, they ...

Captive marmosets that listened in on recorded vocal interactions between other monkeys appeared to understand what they overheard - and formed judgements about one of the interlocutors as a result, according to behavioral analyses and thermal measurements that corresponded with the marmosets' emotional states. The findings suggest that the eavesdropping monkeys perceived these vocalizations as "conversations" rather than isolated elements and indicate that, on the whole, they prefer to interact with cooperative rather than noncooperative individuals. However, the researchers observed notable differences in how male or female and breeder or helper animals (those without their own offspring) reacted after eavesdropping. While behavioral ...

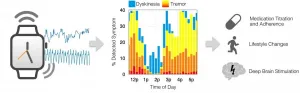

Scientists have developed a monitoring system based on commercial smartwatches that can detect movement issues and tremors in patients with Parkinson's disease. The system was tested in a study involving 343 patients - including 225 who the researchers followed for 6 months. The system gave evaluations that matched a clinician's estimates in 94% of the subjects. The findings suggest the platform could allow clinicians to remotely monitor the progression of a patient's condition and adjust medication plans accordingly to improve outcomes. Parkinson's disease is marked by a breakdown in voluntary movement ...

Participants in an international survey study reported greater willingness to reshare a call for social distancing if the message was endorsed by well-known immunology expert Anthony Fauci, rather than a government spokesperson or celebrity. Ahmad Abu-Akel of the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, and colleagues Andreas Spitz and Robert West of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, report these findings in the open-access journal PLOS ONE on February 3.

Previous research has extensively explored how to maximize the effectiveness of public health messages by altering their style and content. However, relatively few studies have examined the impact of spokesperson identity on the effectiveness of health messages, especially during crises like the ongoing COVID-19 ...

DALLAS - Feb. 3, 2021 - Inactivating a gene in young songbirds that's closely linked with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) prevents the birds from forming memories necessary to accurately reproduce their fathers' songs, a new study led by UT Southwestern shows.

The findings, published online today in Science Advances, may help explain the deficits in speech and language that often accompany ASD and could eventually lead to new treatments specifically targeting this aspect of the disorder.

Study leader Todd Roberts, Ph.D., associate professor of neuroscience and a member of the Peter O'Donnell Jr. Brain Institute at UT Southwestern, explains that the vocalizations that comprise a central part of human communication are relatively unique among ...