(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Muscle wasting, or the loss of muscle tissue, is a common problem for people with cancer, but the precise mechanisms have long eluded doctors and scientists. Now, a new study led by Penn State researchers gives new clues to how muscle wasting happens on a cellular level.

Using a mouse model of ovarian cancer, the researchers found that cancer progression led to fewer skeletal muscle ribosomes -- particles in the cell that make proteins. Because muscle mass is mainly determined by protein synthesis, having less ribosomes likely explains why muscles waste away in cancer.

Gustavo Nader, associate professor of kinesiology and physiology at Penn State, said the findings suggest a mechanism for muscle wasting that could be relevant not just for people with cancer, but other conditions as well.

"Loss of muscle mass is also associated with the aging process, malnutrition, and people with COVID-19 and HIV-AIDS, among others," Nader said. "Not only is muscle wasting a common problem, but there's currently no cure or treatment, either. But now that we understand the mechanism better, we can move forward with trying to find ways to reverse that mechanism."

According to the researchers, significant muscle wasting -- or "cachexia" -- occurs in about 80% of people with cancer and is responsible for about 30% of cancer deaths. It's also associated with a reduced quality of life, problems tolerating chemotherapy and lower survival rates. According to Nader, "cachexia is often the killer, not the tumor."

Nader said that because there is no current cure or treatment for cachexia, it is vital for scientists to understand precisely how and why it happens. But while there has been a lot of research trying to understand and prevent the mechanism that causes muscles to waste, Nader and his team wanted to tackle the problem from a new angle.

"Most of the focus has been on protein degradation, where people have tried to block proteins from being chopped up, or degraded, in order to prevent the loss of muscle mass," Nader said. "But many of those efforts have failed, and one reason may be because people forgot about the protein synthesis aspect of it, which is the process of creating new proteins. That's what we tackled in this study."

For the study, the team used a pre-clinical mouse model of ovarian cancer with significant muscle loss. By using mice, the researchers were able to study the progression of cancer cachexia over time which would be difficult to do with human patients.

After analyzing their results, the researchers found that mice with tumors experienced a rapid loss of muscle mass and a dramatic reduction in the ability to synthesize new proteins, which can be explained by a drop in the amount of ribosomes in their muscles.

"So we cracked the first layer of this problem, because we showed that there are less ribosomes and less protein synthesis," Nader said.

Then, the researchers set out to explain why the number of ribosomes was decreased. After examining the ribosomal genes, they found that once a tumor was present, the expression of the ribosomal genes started to decrease until it reached a level that made it impossible for the muscles to produce enough ribosomes to maintain enough protein synthesis to prevent muscle loss.

Nader said that while more research is needed, he hopes the findings -- recently published in the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology Journal -- can eventually contribute to prevent people from losing muscle mass and function.

"If we can better understand how muscles make ribosomes, we will be able to find new treatments to both stimulate muscle growth and prevent muscle wasting," Nader said. "This is especially important considering that current approaches to block tumor progression target the ribosomal production machinery, and because these drugs are given systemically, they will likely affect all tissues in the body and will also impair muscle building."

INFORMATION:

Hyo-Gun Kim, Penn State; Joshua R. Huot, Indiana University School of Medicine; Fabrizio Pin, Indiana University School of Medicine; Bin Guo, Penn State; and Andrea Bonetto, Indiana University School of Medicine, also participated in this work.

The National Institutes of Health helped support this research.

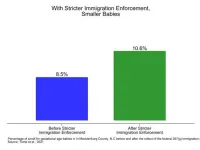

DURHAM, N.C. -- Harsher immigration law enforcement by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement leads to decreased use of prenatal care for immigrant mothers and declines in birth weight, according to new Duke University research.

In the study, published in PLOS ONE, researchers examine the effects of the federal 287(g) immigration program after it was introduced in North Carolina in 2006. Under 287(g) programs, which are still in effect, local law officers are deputized to act as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents, with authority to question individuals about immigration status, detain them, and if necessary, begin deportation proceedings.

According to the study findings, the 2006 policy change reduced birth weight ...

BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Hypoxia -- where a tissue is deprived of an adequate supply of oxygen -- is a feature inside solid cancer tumors that renders them highly invasive and resistant to treatment. Study of how cells adapt to this critical stressor, by altering their metabolism to survive in a low-oxygen environment, is important to better understand tumor growth and spread.

Researchers led by Rajeev Samant, Ph.D., professor of pathology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, now report that chronic hypoxia, surprisingly, upregulates RNA polymerase I activity and alters the methylation patterns on ribosomal RNAs. These altered epigenetic marks on the ribosomal RNAs appear to create a pool of specialized ribosomes that can differentially ...

As a native animal, kangaroos aren't typically considered a threat to Australian vegetation.

While seen as a pest on farmland - for example, when competing with livestock for resources - they usually aren't widely seen as a pest in conservation areas.

But a new collaborative study led by UNSW Sydney found that conservation reserves are showing signs of kangaroo overgrazing - that is, intensive grazing that negatively impacts the health and biodiversity of the land.

Surprisingly, the kangaroos' grazing impacts appeared to be more damaging to the land than rabbits, an introduced species.

"The kangaroos had severe impacts on soils and vegetation that were symptomatic of overgrazing," says Professor Michael Letnic, senior author of the paper and ...

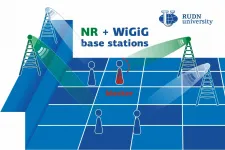

Mathematicians from RUDN University suggested and tested a new method to assess the productivity of fifth-generation (5G) base stations. The new technology would help get rid of mobile access stations and even out traffic fluctuations. The results of the study were published in the IEEE Conference Publication.

Stations of the new 5G New Radio (NR) communication standard developed by the 3GPP consortium are expected to shortly be installed in large quantities all over the world. First of all, the stations will be deployed in places with high traffic ...

ITHACA, N.Y. -Wind energy scientists at Cornell University have released a new global wind atlas - a digital compendium filled with documented extreme wind speeds for all parts of the world - to help engineers select the turbines in any given region and accelerate the development of sustainable energy.

This wind atlas is the first publicly available, uniform and geospatially explicit (datasets tied to locations) description of extreme wind speeds, according to the research, "A Global Assessment of Extreme Wind Speeds For Wind Energy Applications," published in Nature Energy.

"Cost-efficient expansion of the wind-energy industry is enabled by access ...

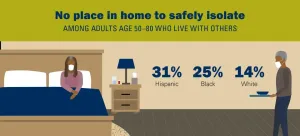

One of the most important ways to stop the spread of COVID-19 is for people who have tested positive, or have symptoms, to isolate themselves from the other people they live with.

But a new University of Michigan poll suggests that nearly one in five older adults don't have the ability to do this - and that those who are Hispanic or Black, or who have lower incomes or poor health to begin with, are more likely to lack a safe isolation place in their home.

The poll also shows significant inequality in another key aspect of staying safe and healthy during the pandemic: the ability to get outside for fresh air and exercise, and to engage safely with friends, ...

Despite worldwide use of lithium batteries, the exact dynamics of their operation has remained elusive. X-rays have proven to be a powerful tool for peering inside of these batteries to see the changes that occur in real time.

Using the ultrabright X-rays of the Advanced Photon Source (APS), a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility at the DOE's Argonne National Laboratory, a research team recently observed the internal evolution of the materials inside solid-state lithium batteries as they were charged and discharged. This detailed 3D ...

The speed of light has come to 3D printing. Northwestern University engineers have developed a new method that uses light to improve 3D printing speed and precision while also, in combination with a high-precision robot arm, providing the freedom to move, rotate or dilate each layer as the structure is being built.

Most conventional 3D printing processes rely on replicating a digital design model that is sliced into layers with the layers printed and assembled upwards like a cake. The Northwestern method introduces the ability to manipulate the original design layer by layer and pivot the printing direction without recreating the model. This "on-the-fly" ...

How do the normal pains of everyday life, such as headaches and backaches, influence our ability to think? Recent studies suggest that healthy individuals in pain also show deficits in working memory, or the cognitive process of holding and manipulating information over short periods of time. Prior research suggests that pain-related impairments in working memory depend on an individual's level of emotional distress. Yet the specific brain and psychological factors underlying the role of emotional distress in contributing to this relationship are not well understood.

A new study, titled "Modeling neural and self-reported factors of affective distress in the relationship between pain and working memory in healthy individuals," and published in the journal ...

LOS ANGELES - New research from the Center for Cardiac Arrest Prevention in the Smidt Heart Institute has found for the first time that during nighttime hours, women are more likely than men to suffer sudden death due to cardiac arrest. Findings were published in the journal Heart Rhythm.

"Dying suddenly during nighttime hours is a perplexing and devastating phenomenon," said Sumeet Chugh, MD, senior author of the study and director of the Center for Cardiac Arrest Prevention. "We were surprised to discover that being female is an independent predictor of these events."

Medical experts are mystified, Chugh says, because during these late hours, most patients are in a resting state, with reduced metabolism, heart rate and blood pressure.

Sudden cardiac arrest-also called sudden cardiac ...