(Press-News.org) Gels are formed by mixing polymers into fluids to create gooey substances useful for everything from holding hair in place to enabling contact lenses to float over the eye.

Researchers want to develop gels for healthcare applications by mixing in medicinal compounds, and giving patients injections so that the gel releases the active pharmaceutical ingredient over a period of months to avoid weekly or daily needle sticks.

But standing in the way is a problem that's as easily understandable as the difference between using hair gel on a beach versus in a blizzard - heat and cold change the character of the gel.

"We can make gels with the right slow-release properties at room temperature but once we injected them, body heat would rapidly dissolve them and release the medicines too quickly," said Eric Appel, assistant professor of materials science and engineering.

In a paper published Feb. 2 in the journal Nature Communications, Appel and his team detail their successful first step toward making temperature-resistant, injectable gels with a concoction designed to cleverly bend the laws of thermodynamics.

Appel explained the science behind this rule-breaking with an analogy to making Jello: the solid ingredients are poured into water, then heated and stirred to mix well. As the mixture cools, the Jello solidifies as the molecules bond together. But if the Jello is reheated, the solid reliquefies.

The Jello example illustrates the interplay between two thermodynamic concepts - enthalpy, which measures the energy added to or subtracted from a material, and entropy, which describes how energy changes make a material more or less orderly at the molecular level. Appel and his team had to make a medicinal Jello that didn't melt, thus losing its time-release properties, when the cool solid was heated by the body.

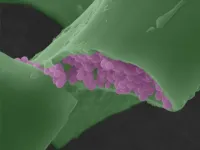

To accomplish this, the Stanford team created a gel made of two solid ingredients - polymers and nanoparticles. The polymers were long, spaghetti-like strands that have a natural propensity to get entangled, and the nanoparticles, only 1/1000th the width of a human hair, encouraged that tendency. The researchers began by separately dissolving the polymers and particles in water and then stirring them together. As the commingling ingredients began to bond, the polymers wrapped tightly around the particles. "We call this our molecular Velcro," said first author Anthony Yu, who did the work as a Stanford graduate student and is now a postdoctoral scholar at MIT.

The powerful affinity between the polymers and particles squeezed out the water molecules that had been caught between them, and as more polymers and particles congealed, the mixture began to gel at room temperature. Crucially, this gelling process was achieved without adding or subtracting energy. When the researchers exposed this gel to the body's temperature (37.5 C) it did not liquefy like ordinary gels because the molecular Velcro effect enabled entropy and enthalpy - orderliness and temperature change, respectively - to remain roughly in balance in accord with thermodynamics.

Appel said it will take more work to make injectable, time-release gels safe for human use. While the polymers in these experiments were biocompatible, the particles were derived from polystyrene, which is commonly used to make disposable cutlery. His lab is already trying to make these thermodynamically-neutral gels with fully biocompatible components.

If they are successful, a time-release gel could prove valuable for providing anti-malarial or anti-HIV treatments in under-resourced areas where it's difficult to administer the short-acting remedies currently available.

"We are trying to make a gel that you could inject with a pin, and then you'd have a little blob that would dissolve away very slowly for three to six months to provide continuous therapy," Appel said. "This would be a game-changer for fighting critical diseases around the world."

INFORMATION:

Assistant Professor of Chemical Engineering Jian Qin, postdoctoral scholars Xian Kong and Hector Lopez Hernandez, and graduate students Huada Lian also co-authored the study.

This work was supported by the Center for Human Systems Immunology with Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Stanford Bio-X Interdisciplinary Initiatives Seed Grants Program, the Kodak Fellowship, and the Stanford Nano Shared Facilities through a National Science Foundation award.

Virtual 'exergaming' has become a popular way to exercise - especially among younger people - since the release of virtual reality (VR) fitness games on consoles such as Nintendo and Playstation.

But while VR is undoubtedly raising fitness games to a whole new level, researchers at the University of South Australia are cautioning players about the potential side effects of VR, particularly in the first hour after playing.

In a new study published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, UniSA researchers investigated the consequences of playing one of the most popular VR exergames - Beat Saber* - finding that one in seven players still ...

Catalysts are key materials in modern society, enabling selective conversion of raw materials into valuable products while reducing waste and saving energy. In case of industrially relevant oxidative dehydrogenation reactions, most known catalyst systems are based on transition metals such as Iron, Vanadium, Molybdenum or Silver. Due to intrinsic drawbacks associated with the use of transition metals, such as rare occurrence, environmentally harmful mining processes, and toxicity, the fact that pure carbon exhibits catalytic activity in this type of reaction and thus has high potential as a sustainable substitution material is of high interest.

To date, the development of carbon-based catalysts for oxidative dehydrogenation reactions may be divided into two ...

UCC palaeontologists have discovered new evidence that the fate of vertebrate animals over the last 400 million years has been shaped by microscopic melanin pigments.

This new twist in the story of animal evolution is based on cutting-edge analyses of melanin granules - melanosomes - in many different fossil and modern vertebrates, including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Melanin and melanosomes have traditionally been linked to outermost body tissues such as skin, hair and feathers, with important roles in UV protection and stiffening of tissues. Analyses of where different animals store melanin in the body, however, show that different vertebrate groups concentrate melanin in different organs, revealing ...

Ultrasound is not only used as an imaging technique but targeted pulses of ultrasound can be used as a highly accurate treatment for a range of brain diseases, for which there were previously only limited treatment options. Over the last few years, several revolutionary techniques of this kind have been developed, primarily in Toronto but also at MedUni Vienna. The Viennese technique improves brain functions by externally activating neurons that are still functional. Improvements can be expected in various neuropsychiatric brain diseases such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, stroke, Multiple Sclerosis, and neuralgia. A review jointly written by ...

Researchers at NUI Galway have identified genomic signatures in women developing the most common type of breast cancer that can be associated with long-term survival. The NUI Galway team analysed the genomes of breast cancer patients to look for associations with survival rates using advanced statistical techniques.

Carried out by Lydia King during her studies in NUI Galway's MSc in Biomedical Genomics programme, the research has been published in the international journal PLOS ONE.

Early detection by national screening programmes and timely treatment for patients diagnosed with "luminal" types of breast cancer have resulted in excellent prognoses with survival rates of over 80% within five years of treatment. The challenge of long-term survival ...

FOOD SCIENCE Sweden takes first, Denmark second and Norway lags at the bottom when it comes to how much organic food is served in canteens, kindergartens and other public sector workplaces across the three Nordic nations. This, according to the results of a new report by the University of Copenhagen. The report details plenty of potential for expanding the conversion to organic food service in the Danish public sector--a topic of discussion across the EU at the moment.

Plate with potatoes and beef

The governments of Denmark, Norway and Sweden are all keen on ramping up the amount of organic food ...

The FinnBrain research of the University of Turku has demonstrated for the first time that the stress the father has experienced in his childhood is connected to the development of the white matter tracts in the child's brain. Whether this connection is transmitted through epigenetic inheritance needs further research.

Evidence from multiple new animal studies demonstrates that the changes in gene function caused by environment can be inherited between generations through gametes. In particular, nutrition and stress have been proven to cause these types of changes. However, these do not alter the nucleic acid sequence of ...

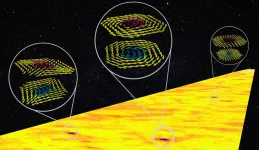

Today's digital world generates vast amounts of data every second. Hence, there is a need for memory chips that can store more data in less space, as well as the ability to read and write that data faster while using less energy.

Researchers from the National University of Singapore (NUS), working with collaborators from the University of Oxford, Diamond Light Source (the United Kingdom's national synchrotron science facility) and University of Wisconsin Madison, have now developed an ultra-thin material with unique properties that could eventually achieve some of these goals. Their ...

A study published in the journal Pediatrics expands validation evidence for a new screening tool that directly engages preschool-age children during clinic visits to assess their early literacy skills. The tool, which is the first of its kind, has the potential to identify reading difficulties as early as possible, target interventions and empower families to help their child at home, according to researchers at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

The Reading House (TRH) is an assessment for ages 3-5 based on a specially designed children's book, which was developed by John Hutton, MD, and his team at Cincinnati Children's. Screening takes five minutes and gauges performance levels ...

An inexpensive, long-lasting and easy-to-administer vaccine against malaria could be a game-changer for millions of people living in countries where the mosquito-borne disease is endemic.

Lucie Jelinkova, a graduate student in the laboratory of Bryce Chackerian, PhD, professor in The University of New Mexico Department of Molecular Genetics & Microbiology, has identified a method that could make that dream into reality.

In research recently published in the journal NPJ Vaccines, Jelinkova and colleagues at Johns Hopkins and Flinders University in Australia report ...