(Press-News.org) Competition among sperm cells is fierce - they all want to reach the egg cell first to fertilize it. A research team from Berlin now shows in mice that the ability of sperm to move progressively depends on the protein RAC1. Optimal amounts of active protein improve the competitiveness of individual sperm, whereas aberrant activity can cause male infertility.

It is literally a race for life when millions of sperm swim towards the egg cells to fertilize them. But does pure luck decide which sperm succeeds? As it turns out, there are differences in competitiveness between individual sperm. In mice, a "selfish" and naturally occurring DNA segment breaks the standard rules of genetic inheritance - and awards a success rate of up to 99 percent to sperm cells containing it.

A team of researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics in Berlin describes how the genetic factor called "t-haplotype" promotes the fertilization success of sperm carrying it.

The researchers for the first time showed experimentally that sperm with the t-haplotype are more progressive, i.e., move faster forward than their "normal" peers, and thereby establish their advantage in fertilization. The researchers analyzed individual sperm and revealed that most of the cells that made only little progress on their paths were genetically "normal", whereas straight moving sperm mostly contained the t-haplotype.

Most importantly, they linked the differences in motility to the molecule RAC1. This molecular switch transmits signals from outside the cell to the inside by activating other proteins. The molecule is known to be involved in directing e.g., white blood cells or cancer cells towards cells exuding chemical signals. The new data suggest that RAC1 might also play a role in directing sperm cells towards the egg, "sniffing" their way to their target.

"The competitiveness of individual sperm seems to depend on an optimal level of active RAC1; both reduced or excessive RAC1 activity interferes with effective forward movement," says Alexandra Amaral, scientist at the MPIMG and first author of the study.

t-sperm poison their competitors

"Sperm with the t-haplotype manage to disable sperm without it," says Bernhard Herrmann, Director at the MPIMG and of the Institute of Medical Genetics at Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and corresponding author of the study. "The trick is that the t?haplotype "poisons" all sperm, but at the same time produces an antidote, which acts only in t-sperm and protects them," explains the scientist. "Imagine a marathon, in which all participants get poisoned drinking water, but some runners also take an antidote."

As he and his colleagues found out, the t-haplotype contains certain gene variants that distort regulatory signals. These distorting factors are established in the early phase of spermatogenesis and get distributed to all sperm of a mouse carrying the t-haplotype. These factors are the "poison" that disturbs progressive movement.

The "antidote" comes into action after the set of chromosomes are split evenly between sperm during their maturation - each sperm cell now containing only half of the chromosomes. Only the half of sperm with the t-haplotype produce an additional factor that reverses the negative effect of the distorter factors. And this protective factor is not distributed, but retained in t-sperm.

t-sperm have no advantage when they are on their own

In sperm from male mice with the t-haplotype only on one of their two chromosomes 17, the researchers observed that some cells move forward and some make little progress. They tested single sperm and found that the genetically "normal" sperm are the ones that are mostly not moving straight. When they treated the mixed population of sperm with a substance that inhibits RAC1, they observed that genetically "normal" sperm now also were able to swim progressively. The advantage of t-sperm was gone, demonstrating that aberrant RAC1 activity perturbs progressive motility.

The results explain why male mice with two copies of the t-haplotype, one on each of the two chromosomes 17, are sterile. They produce only sperm that carry the t-haplotype. These cells have much higher levels of active RAC1 than sperm from genetically normal mice, as the researchers now found out, and are almost immotile.

But sperm from normal mice treated with the RAC1 inhibitor also lost their ability to move progressively. Thus, too low RAC1 activity also is disadvantageous. Aberrant RAC1 activity might also be underlying particular forms of male infertility in men, speculate the researchers.

"Our data highlight the fact that sperm cells are ruthless competitors," says Herrmann. Furthermore, the example of the t-haplotype demonstrates how some genes use somewhat dirty tricks to get passed on. "Genetic differences can give individual sperm an advantage in the race for life, thus promoting the transmission of particular gene variants to the next generation," says the scientist.

INFORMATION:

Original publication

Alexandra Amaral and Bernhard G Herrmann (2021)

RAC1 controls progressive movement and competitiveness of mammalian spermatozoa.

PLoS Genetics

Berkeley -- In the arid Mojave Desert, small burrowing mammals like the cactus mouse, the kangaroo rat and the white-tailed antelope squirrel are weathering the hotter, drier conditions triggered by climate change much better than their winged counterparts, finds a new study published today in Science.

Over the past century, climate change has continuously nudged the Mojave's searing summer temperatures ever higher, and the blazing heat has taken its toll on the desert's birds. Researchers have documented a collapse in the region's bird populations, likely resulting ...

Treatment for HIV has improved tremendously over the past 30 years; once a death sentence, the disease is now a manageable lifelong condition in many parts of the world. Life expectancy is about the same as that of individuals without HIV, though patients must adhere to a strict regimen of daily antiretroviral therapy, or the virus will come out of hiding and reactivate. Antiretroviral therapy prevents existing virus from replicating, but it can't eliminate the infection. Many ongoing clinical trials are investigating possible ways to clear HIV infection.

In a study published Feb. 4 in the journal Science, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have identified a potential way to eradicate ...

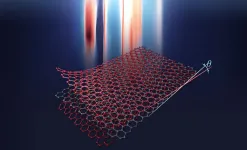

In 2018, the physics world was set ablaze with the discovery that when an ultrathin layer of carbon, called graphene, is stacked and twisted to a "magic angle," that new double layered structure converts into a superconductor, allowing electricity to flow without resistance or energy waste. Now, in a literal twist, Harvard scientists have expanded on that superconducting system by adding a third layer and rotating it, opening the door for continued advancements in graphene-based superconductivity.

The work is described in a new paper in Science and can one day help lead toward superconductors that operate at higher or even close to room temperature. These superconductors are considered the holy grail of condensed matter physics ...

Black children have significantly higher rates of shellfish and fish allergies than White children, in addition to having higher odds of wheat allergy, suggesting that race may play an important role in how children are affected by food allergies, researchers at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, Rush University Medical Center and two other hospitals have found.

Results of the study were published in the February issue of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice.

"Food allergy is a common condition in the U.S., and we know from our previous research that there are important differences between Black and White children with food allergy, but there is so much we need to know to be able to help our patients ...

In a new perspective piece published in the Feb. 5 issue of Science, pharmacologist Namandje Bumpus, Ph.D. -- who recently became the first African American woman to head a Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine department, and is the only African American woman leading a pharmacology department in the country -- outlines the molecular origins for differences in how well certain drugs work among distinct populations. She also lays out a four-part plan to improve the equity of drug development.

"Human beings are more similar than we are different," says Bumpus. "Yet, the slightest variations in our genetic material ...

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected people's behavior everywhere. Fear, apprehensiveness, sadness, anxiety, and other troublesome feelings have become part of the daily lives of many families since the first cases of the disease were officially recorded early last year.

These turbulent feelings are often expressed in dreams reflecting a heavier burden of mental suffering, fear of contamination, stress caused by social distancing, and lack of physical contact with others. In addition, dream narratives in the period include a larger proportion of terms relating to cleanliness and contamination, as well as anger and sadness.

All this is reported in a study published in PLOS ONE. The principal investigator was Natália ...

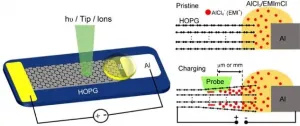

Surface and interface play critical roles in energy storage devices, thus calling for in-situ/operando methods to probe the electrified surface/interface. However, the commonly used in-situ/operando characterization techniques such as X-ray diffraction (XRD), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray spectroscopy and topography, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) are based on the structural, electronic and chemical information in bulk region of the electrodes or electrolytes.

Surface science methodology including electron spectroscopy and scanning probe microscopy can provide rich information about how reactions ...

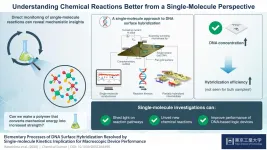

Scientists globally aim to control chemical reactions--an ambitious goal that requires identifying the steps taken by initial reactants to arrive at the final products as the reaction takes place. While this dream remains to be realized, techniques for probing chemical reactions have become sufficiently advanced to render it possible. In fact, chemical reactions can now be monitored based on the change of electronic properties of a single molecule! Thanks to the scanning tunneling microscope (STM), this is also simple to accomplish. Why not then utilize ...

Plastics are among the most successful materials of modern times. However, they also create a huge waste problem. Scientists from the University of Groningen (The Netherlands) and the East China University of Science and Technology (ECUST) in Shanghai produced different polymers from lipoic acid, a natural molecule. These polymers are easily depolymerized under mild conditions. Some 87 per cent of the monomers can be recovered in their pure form and re-used to make new polymers of virgin quality. The process is described in an article that was published in the journal Matter on 4 February.

A problem with recycling plastics is that it usually results in a lower-quality product. The best results are obtained by chemical recycling, in which the polymers are broken ...

A pilot program to offer mental health services offered resident physicians at the University of Colorado School of Medicine provides a model for confidential and affordable help, according to an article published today by the journal Academic Medicine.

For the 2017-2018 class, 80 resident physicians in the internal medicine and in internal medicine-pediatrics programs were enrolled in a mental health program that provided scheduled appointments at the campus mental health center. Residents were allowed to opt-out of the appointments. The cost of the appointments was covered by the residency programs, not charged to residents. Programs received ...