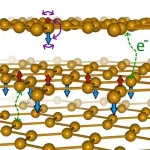

(Press-News.org) Researchers have identified a new form of magnetism in so-called magnetic graphene, which could point the way toward understanding superconductivity in this unusual type of material.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge, were able to control the conductivity and magnetism of iron thiophosphate (FePS3), a two-dimensional material which undergoes a transition from an insulator to a metal when compressed. This class of magnetic materials offers new routes to understanding the physics of new magnetic states and superconductivity.

Using new high-pressure techniques, the researchers have shown what happens to magnetic graphene during the transition from insulator to conductor and into its unconventional metallic state, realised only under ultra-high pressure conditions. When the material becomes metallic, it remains magnetic, which is contrary to previous results and provides clues as to how the electrical conduction in the metallic phase works. The newly discovered high-pressure magnetic phase likely forms a precursor to superconductivity so understanding its mechanisms is vital.

Their results, published in the journal Physical Review X, also suggest a way that new materials could be engineered to have combined conduction and magnetic properties, which could be useful in the development of new technologies such as spintronics, which could transform the way in which computers process information.

Properties of matter can alter dramatically with changing dimensionality. For example, graphene, carbon nanotubes, graphite and diamond are all made of carbon atoms, but have very different properties due to their different structure and dimensionality.

"But imagine if you were also able to change all of these properties by adding magnetism," said first author Dr Matthew Coak, who is jointly based at Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory and the University of Warwick. "A material which could be mechanically flexible and form a new kind of circuit to store information and perform computation. This is why these materials are so interesting, and because they drastically change their properties when put under pressure so we can control their behaviour."

In a previous study by Sebastian Haines of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory and the Department of Earth Sciences, researchers established that the material becomes a metal at high pressure, and outlined how the crystal structure and arrangement of atoms in the layers of this 2D material change through the transition.

"The missing piece has remained however, the magnetism," said Coak. "With no experimental techniques able to probe the signatures of magnetism in this material at pressures this high, our international team had to develop and test our own new techniques to make it possible."

The researchers used new techniques to measure the magnetic structure up to record-breaking high pressures, using specially designed diamond anvils and neutrons to act as the probe of magnetism. They were then able to follow the evolution of the magnetism into the metallic state.

"To our surprise, we found that the magnetism survives and is in some ways strengthened," co-author Dr Siddharth Saxena, group leader at the Cavendish Laboratory. "This is unexpected, as the newly-freely-roaming electrons in a newly conducting material can no longer be locked to their parent iron atoms, generating magnetic moments there - unless the conduction is coming from an unexpected source."

In their previous paper, the researchers showed these electrons were 'frozen' in a sense. But when they made them flow or move, they started interacting more and more. The magnetism survives, but gets modified into new forms, giving rise to new quantum properties in a new type of magnetic metal.

How a material behaves, whether conductor or insulator, is mostly based on how the electrons, or charge, move around. However, the 'spin' of the electrons has been shown to be the source of magnetism. Spin makes electrons behave a bit like tiny bar magnets and point a certain way. Magnetism from the arrangement of electron spins is used in most memory devices: harnessing and controlling it is important for developing new technologies such as spintronics, which could transform the way in which computers process information.

"The combination of the two, the charge and the spin, is key to how this material behaves," said co-author Dr David Jarvis from the Institut Laue-Langevin, France, who carried out this work as the basis of his PhD studies at the Cavendish Laboratory. "Finding this sort of quantum multi-functionality is another leap forward in the study of these materials."

"We don't know exactly what's happening at the quantum level, but at the same time, we can manipulate it," said Saxena. "It's like those famous 'unknown unknowns': we've opened up a new door to properties of quantum information, but we don't yet know what those properties might be."

There are more potential chemical compounds to synthesise than could ever be fully explored and characterised. But by carefully selecting and tuning materials with special properties, it is possible to show the way towards the creation of compounds and systems, but without having to apply huge amounts of pressure.

Additionally, gaining fundamental understanding of phenomena such as low-dimensional magnetism and superconductivity allows researchers to make the next leaps in materials science and engineering, with particular potential in energy efficiency, generation and storage.

As for the case of magnetic graphene, the researchers next plan to continue the search for superconductivity within this unique material. "Now that we have some idea what happens to this material at high pressure, we can make some predictions about what might happen if we try to tune its properties through adding free electrons by compressing it further," said Coak.

"The thing we're chasing is superconductivity," said Saxena. "If we can find a type of superconductivity that's related to magnetism in a two-dimensional material, it could give us a shot at solving a problem that's gone back decades."

INFORMATION:

A Rochester Institute of Technology researcher has validated a tool measuring adherence to a popular child feeding approach used by pediatricians, nutritionists, social workers and child psychologists to assess parents' feeding practices and prevent feeding problems.

The best-practice approach, known as the Satter Division of Responsibility in Feeding, has now been rigorously tested and peer reviewed, resulting in the quantifiable tool sDOR.2-6y. The questionnaire will become a standard parent survey for professionals and researchers working in the early childhood development field, predicts lead researcher ...

Astronomers may have found our galaxy's first example of an unusual kind of stellar explosion. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, adds to the understanding of how some stars shatter and seed the universe with elements critical for life on Earth.

This intriguing object, located near the center of the Milky Way, is a supernova remnant called Sagittarius A East, or Sgr A East for short. Based on Chandra data, astronomers previously classified the object as the remains of a massive star that exploded as a supernova, one of many kinds of exploded stars that scientists have catalogued.

Using longer Chandra observations, a team of astronomers has now instead concluded that the object is left over from a different type of ...

Findings from a new study on Alzheimer's disease (AD), led by researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), could eventually help clinicians identify people at highest risk for developing the irreversible, progressive brain disorder and pave the way for treatments that slow or prevent its onset.

The research, published in the journal Scientific Reports in early January, has demonstrated that a shorter form of the protein peptide believed responsible for causing AD (beta-amyloid 42, or Aβ42) halts the damage-causing mechanism of ...

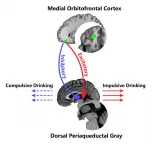

A pathway in the brain where alcohol addiction first develops has been identified by a team of British and Chinese researchers in a new study

Could lead to more effective interventions when tackling compulsive and impulsive drinking

More than 3 million deaths every year are related to alcohol use globally, according to the World Health Organisation

The physical origin of alcohol addiction has been located in a network of the human brain that regulates our response to danger, according to a team of British and Chinese researchers, co-led by the University of Warwick, the University ...

On a brisk November morning in 2018, a fire sparked in a remote stretch of canyon in Butte County, California, a region nestled against the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Fueled by a sea of tinder created by drought, and propelled by powerful gusts, the flames grew and traveled rapidly. In less than 24 hours, the fire had swept through the town of Paradise and other communities, leaving a charred ruin in its wake.

The Camp Fire was the costliest disaster worldwide in 2018 and, having caused 85 deaths and destroyed more than 18,000 buildings, it became both the deadliest and most destructive wildfire ...

An unusual biologically active porphyrin compound was isolated from seabed dweller Ophiura sarsii. The substance might be used as an affordable light-sensitive drug for innovative photodynamic therapy and for targeted treatment of triple-negative breast cancer and some other cancers. Researchers from the School of Biomedicine of Far Eastern Federal University (FEFU) and the University of Geneva reported the findings in Marine Drugs.

The seabed dweller Ophiura sarsii, the source of the new compound, was isolated at a depth of 15-18 meters in Bogdanovich Bay, Russky Island (Vladivostok, Russia). Ophiuras may resemble ...

DALLAS - Feb. 8, 2021 - Pregnant women, who are at increased risk of preterm birth or pregnancy loss if they develop a severe case of COVID-19, need the best possible guidance on whether they should receive a COVID-19 vaccine, according to an article by two UT Southwestern obstetricians published today in JAMA. That guidance can take lessons from what is already known about other vaccines given during pregnancy.

In the Viewpoint article, Emily H. Adhikari, M.D., and Catherine Y. Spong, M.D., describe how the available safety and effectiveness data, basic science of mRNA vaccines, and long history ...

DALLAS - Feb. 8, 2021 - A new nanoparticle-based drug can boost the body's innate immune system and make it more effective at fighting off tumors, researchers at UT Southwestern have shown. Their study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, is the first to successfully target the immune molecule STING with nanoparticles about one millionth the size of a soccer ball that can switch on/off immune activity in response to their physiological environment.

"Activating STING by these nanoparticles is like exerting perpetual pressure on the accelerator to ramp up the natural innate immune response to a tumor," says study leader Jinming Gao, Ph.D., a professor in UT Southwestern's Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive ...

AURORA, Colo. (February 8, 2021) - Researchers from the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have found that immune responses to insulin could help identify individuals most at risk for developing Type 1 diabetes.

The study, out recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, measured immune responses from individuals genetically predisposed to developing Type 1 diabetes (T1D) to naturally occurring insulin and hybrid insulin peptides. Since not all genetically predisposed individuals ...

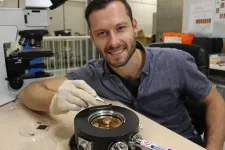

An international team of scientists has invented the equivalent of body armour for extremely fragile quantum systems, which will make them robust enough to be used as the basis for a new generation of low-energy electronics.

The scientists applied the armour by gently squashing droplets of liquid metal gallium onto the materials, coating them with gallium oxide.

Protection is crucial for thin materials such as graphene, which are only a single atom thick - essentially two-dimensional (2D) - and so are easily damaged by conventional layering technology, said Matthias Wurdack, who is the lead author of the group's publication in Advanced Materials.

"The protective coating ...