Neural roots/origins of alcoholism identified by British and Chinese researchers

2021-02-08

(Press-News.org) A pathway in the brain where alcohol addiction first develops has been identified by a team of British and Chinese researchers in a new study

Could lead to more effective interventions when tackling compulsive and impulsive drinking

More than 3 million deaths every year are related to alcohol use globally, according to the World Health Organisation

The physical origin of alcohol addiction has been located in a network of the human brain that regulates our response to danger, according to a team of British and Chinese researchers, co-led by the University of Warwick, the University of Cambridge, and Fudan University in Shanghai.

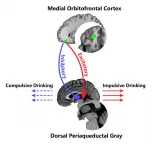

The medial orbitofrontal cortex (mOFC) at the front of the brain senses an unpleasant or emergency situation, and then sends this information to the dorsal periaqueductal gray (dPAG) at the brain's core, the latter area processing whether we need to escape the situation.

A person is at greater risk of developing alcohol use disorders when this information pathway is imbalanced in the following two ways:

Alcohol inhibits the dPAG (the area of the brain that processes adverse situations), so that the brain cannot respond to negative signals, or the need to escape from danger -- leading a person to only feel the benefits of drinking alcohol, and not its harmful side effects. This is a possible cause of compulsive drinking.

A person with alcohol addiction will also generally have an over-excited dPAG, making them feel that they are in an adverse or unpleasant situation they wish to escape, and they will urgently turn to alcohol to do so. This is the cause of impulsive drinking.

Professor Jianfeng Feng, from the Department of Computer Science at the University of Warwick and who also teaches at Fudan University, comments:

"I was invited to comment on a previous study on mice for the similar purpose: to locate the possible origins of alcohol abuse. It is exciting that we can replicate these murine models in humans, and, of course, go a step further to identify a dual-pathway model that links alcohol abuse to a tendency to exhibit impulsive behaviour."

Professor Trevor Robbins from the Dept of Psychology at the University of Cambridge comments: "It is remarkable that these neural systems in the mouse concerned with responding to threat and punishment have been shown to be relevant to our understanding of the factors leading to alcohol abuse in adolescents."

Dr Tianye Jia from the Institute of Science and Technology for Brain-inspired Intelligence at Fudan University, also affiliated with King's College London, comments

"We have found that the same neural top-down regulation could malfunction in two completely different ways, yet leading to similar alcohol abuse behaviour."

Published in the journal Science Advances, the research is led by an international collaboration, co-led by Dr Tianye Jia from Fudan University, Professor Jianfeng Feng from the University of Warwick and Fudan University, and Professor Trevor Robbins from the University of Cambridge and Fudan University.

The research team had noticed that previous rodent models showed that the mPFC and dPAG brain areas could underlie precursors of alcohol dependence.

They then analysed MRI brain scans from the IMAGEN dataset -- a group of 2000 individuals from the UK, Germany, France and Ireland who take part in scientific research to advance knowledge of how biological, psychological and environmental factors during adolescence may influence brain development and mental health.

The participants undertook task-based functional MRI scans, and when they did not receive rewards in the tasks (which produced negative feelings of punishment), regulation between the mOFC and dPAG was inhibited more highly in participants who had exhibited alcohol abuse.

Equally, in a resting state, participants who demonstrated a more overexcited regulation pathway between the mOFC and dPAG, (leading to feelings of needing urgently to escape a situation), also had increased levels of alcohol abuse.

Alcohol use disorder (AUD) is one of the most common and severe mental illnesses. According to a WHO report in 2018, more than 3 million deaths every year are related to alcohol use worldwide, and harmful alcohol use contributes to 5.1% of the global burden of disease. Understanding how alcohol addiction forms in the human brain could lead to more effective interventions to tackle the global problem of alcohol abuse.

INFORMATION:

FEBRUARY 2021

NOTES TO EDITORS

Paper available to view please use the contact details below.

High-res images available at: https://warwick.ac.uk/services/communications/medialibrary/images/february_2021/dorsal_-_jpeg_.jpg

Caption: The Medial Orbitofrontal Cortex - Dorsal Periaqueductal Gray top-down regulations are linked to impulsive and compulsive drinking.

Credit: University of Warwick

For further information please contact:

Alice Scott

Media Relations Manager - Science

University of Warwick

Tel: +44 (0) 7920 531 221

E-mail: alice.j.scott@warwick.ac.uk

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-08

On a brisk November morning in 2018, a fire sparked in a remote stretch of canyon in Butte County, California, a region nestled against the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Fueled by a sea of tinder created by drought, and propelled by powerful gusts, the flames grew and traveled rapidly. In less than 24 hours, the fire had swept through the town of Paradise and other communities, leaving a charred ruin in its wake.

The Camp Fire was the costliest disaster worldwide in 2018 and, having caused 85 deaths and destroyed more than 18,000 buildings, it became both the deadliest and most destructive wildfire ...

2021-02-08

An unusual biologically active porphyrin compound was isolated from seabed dweller Ophiura sarsii. The substance might be used as an affordable light-sensitive drug for innovative photodynamic therapy and for targeted treatment of triple-negative breast cancer and some other cancers. Researchers from the School of Biomedicine of Far Eastern Federal University (FEFU) and the University of Geneva reported the findings in Marine Drugs.

The seabed dweller Ophiura sarsii, the source of the new compound, was isolated at a depth of 15-18 meters in Bogdanovich Bay, Russky Island (Vladivostok, Russia). Ophiuras may resemble ...

2021-02-08

DALLAS - Feb. 8, 2021 - Pregnant women, who are at increased risk of preterm birth or pregnancy loss if they develop a severe case of COVID-19, need the best possible guidance on whether they should receive a COVID-19 vaccine, according to an article by two UT Southwestern obstetricians published today in JAMA. That guidance can take lessons from what is already known about other vaccines given during pregnancy.

In the Viewpoint article, Emily H. Adhikari, M.D., and Catherine Y. Spong, M.D., describe how the available safety and effectiveness data, basic science of mRNA vaccines, and long history ...

2021-02-08

DALLAS - Feb. 8, 2021 - A new nanoparticle-based drug can boost the body's innate immune system and make it more effective at fighting off tumors, researchers at UT Southwestern have shown. Their study, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, is the first to successfully target the immune molecule STING with nanoparticles about one millionth the size of a soccer ball that can switch on/off immune activity in response to their physiological environment.

"Activating STING by these nanoparticles is like exerting perpetual pressure on the accelerator to ramp up the natural innate immune response to a tumor," says study leader Jinming Gao, Ph.D., a professor in UT Southwestern's Harold C. Simmons Comprehensive ...

2021-02-08

AURORA, Colo. (February 8, 2021) - Researchers from the Barbara Davis Center for Childhood Diabetes at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus have found that immune responses to insulin could help identify individuals most at risk for developing Type 1 diabetes.

The study, out recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, measured immune responses from individuals genetically predisposed to developing Type 1 diabetes (T1D) to naturally occurring insulin and hybrid insulin peptides. Since not all genetically predisposed individuals ...

2021-02-08

An international team of scientists has invented the equivalent of body armour for extremely fragile quantum systems, which will make them robust enough to be used as the basis for a new generation of low-energy electronics.

The scientists applied the armour by gently squashing droplets of liquid metal gallium onto the materials, coating them with gallium oxide.

Protection is crucial for thin materials such as graphene, which are only a single atom thick - essentially two-dimensional (2D) - and so are easily damaged by conventional layering technology, said Matthias Wurdack, who is the lead author of the group's publication in Advanced Materials.

"The protective coating ...

2021-02-08

A framework designed to provide detailed information on agricultural groundwater use in arid regions has been developed by KAUST researchers in collaboration with the Saudi Ministry of Environment Water and Agriculture (MEWA).

"Groundwater is a precious resource, but we don't pay for it to grow our food, we just pump it out," says Oliver López, who worked on the project with KAUST's Matthew McCabe and co-workers. "When something is free, we are less likely to keep track of it, but it is critical that we measure groundwater extraction because it impacts both food and water security, not just regionally, but globally."

Saudi Arabia's farmland is often irrigated via center pivots that tap underground aquifer sources. The team has built a powerful tool ...

2021-02-08

Osaka, Japan - Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) has a strong osteogenic (bone forming) ability. BMP has already been clinically applied to spinal fusion and non-union fractures. However, dose-dependent side effects related to BMP use, such as inflammatory reactions at the administration site, prevent widespread use.

For safe use, it was necessary to clarify how the BMP signaling pathway is controlled. In a report published in Bone Research, a group of researchers from Osaka University and Ehime University has recently identified a novel role for the protein Smurf2 in regulating bone formation by BMP.

When BMP transmits its message within cells, it can induce rapid bone formation. Previous studies have shown that Smurf2 can control another similar ...

2021-02-08

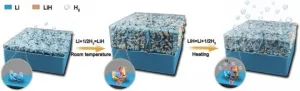

Lithium metal batteries could double the amount of energy held by lithium-ion batteries, if only their anodes didn't break down into small pieces when they were used.

Now, researchers led by Prof. CUI Guanglei from the Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology (QIBEBT) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) have identified what causes lithium metal batteries (LMBs) to "self-destruct" and proposed a way to prevent it. The findings were published in Angewandte Chemie on Jan. 19.

This offers hope of radically enhancing the energy held in batteries without any increase in their size, and at reduced cost.

In fact, LMBs were the original concept for long-lasting ...

2021-02-08

Tiny nanoparticles can be furnished with dyes and could be used for new imaging techniques, as chemists and physicists at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU) show in a recent study. The researchers have also been the first to fully determine the particles' internal structure. Their results were published in the renowned journal Angewandte Chemie.

Single-chain nanoparticles (SCNPs) are an attractive material for chemical and biomedical applications. They are created from just a single chain of molecules that folds into a particle whose circumference measures three to five nanometres. "Because they are so small, they can travel everywhere in the human body and be used for a wide variety of purposes," says Professor Wolfgang ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Neural roots/origins of alcoholism identified by British and Chinese researchers