(Press-News.org) A tiny population of neurons known to be important to appetite appear to also have a significant role in depression that results from unpredictable, chronic stress, scientists say.

These AgRP neurons reside exclusively in the bottom portion of the hypothalamus called the arcuate nucleus, or ARC, and are known to be important to energy homeostasis in the body as well prompting us to pick up a fork when we are hungry and see food.

Now Medical College of Georgia scientists and their colleagues report the first evidence that, not short-term stress, like a series of tough college exams, rather chronic, unpredictable stress like that which erupts in our personal and professional lives, induces changes in the function of AgRP neurons that may contribute to depression, they write.

The small number of AgRP neurons likely are logical treatment targets for depression, says Dr. Xin-Yun Lu, chair of the Department of Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at MCG at Augusta University and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Translational Neuroscience.

While it's too early to say if the shift in neuron activity prompted by chronic stress and associated with depression starts with these neurons, they are a definite and likely key piece of the puzzle, says Lu, corresponding author of the study in the journal Molecular Psychiatry.

"It is clear that when we manipulate these neurons, it changes behavioral reactions," she says, but many questions remain, like how these AgRP neurons in the human brain help us cope with and adapt to unpredictable chronic stress over time.

They have shown this type of stress, which results in an animal model of depression, decreases the activity of AgRP, or agouti-related protein, neurons, decreasing the neurons' ability to spontaneously fire, increasing firing irregularities and otherwise altering the usual firing properties of AgRP neurons in both their male and female mouse model of depression.

Additionally, when they used a small molecule to directly inhibit the neurons, it increased their susceptibility to chronic, unpredictable stress, inducing depression-like behavior in the mice, including reducing usual desires for rewards like consuming palatable sucrose and sex. When they activated the neurons, it reversed classic depressive behaviors like despair and the inability to experience pleasure.

"We can remotely stimulate those neurons and reverse depression," Lu says, using a synthetic small molecule agonist that binds to an also manmade chemogenetic receptor in their target neurons -- a common method for studying the relationship between behavior and particular neurons -- delivered directly to those neurons via a viral vector.

As in life, unpredictability can increase stress' impact, Lu says, so they also used that approach in their studies, with techniques like social isolation and switching light and dark cycles, and found that mice began exhibiting depressive behavior by 10 days.

The scientists found that the stress-related decrease in AgRP neuron activity seems to produce an increase in the activity of other nearby neuron types in the ARC, and are pursuing that observation further. They also are looking at adjustments that may happen to other neurons that respond to stress and reward in other subregions of the hypothalamus as well as other parts of the brain to help define the circuitry involved.

They also already are looking at the more time-consuming process of assessing whether removing the chronic stressors alone will also eventually result in the AgRP neurons resuming more normal activity.

Major depression is one of the most common mental health disorders in the United States, according to the National Institute of Mental Health, with an estimated 17.3 million adults experiencing at least one episode. Prevalence rates are highest among 18-25 year olds, females having about twice the risk of men, and depression can run in families.

Only about one-third of patients achieve full remission with existing treatments and anhedonia, the inability to experience pleasure, which increases suicide risk, typically is the last symptom to resolve. However, mechanisms behind depression's effects remain poorly understood, the scientists say.

"We want to find better ways to treat it, including more targeted treatments that may reduce side effects, which often are significant enough to prompt patients to stop taking them," Lu says. Undesirable effects can include weight gain and insomnia.

Prozac, for example, reduces the uptake of serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, but serotonin also has important functions like regulating the sleep cycle, and sleep disturbances are an established side effect of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors.

While it's unknown if some of the existing antidepressants happen to impact AgRP neurons, it's possible that new therapies designed to target the neurons could also produce weight gain because of the neurons' role in feeding behavior and metabolism, Lu notes.

Lu was among the scientists who earlier characterized the network of AgRP neurons in the brain, and was the first to show fluctuations in the production of AgRP over the course of the day and that a surge of glucocorticoid stress hormones comes before peak expression of AgRP and feeding.

The new study shows that AgRP neurons are a key component to the neural circuitry underlying depression-like behavior, they write, and chronic stress causes AgRP dysfunction. They suspect one reason for the reduced excitability of the neurons is increased sensitivity to the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA.

AgRP neurons are stimulated by hunger signals and inhibited by satiety. Previous studies have shown that when activated, AgRP neurons can produce significant increases in eating that can result in significant weight gain. Activating these neurons in mice, in fact, increases their eating and food seeking. Just the presence of food increases the firing of AgRP neurons, reinforcing that you are hungry and driving you to pick up that fork, Lu says of the neuron sometimes dubbed the hanger neuron.

Eliminating AgRP neurons conversely suppresses feeding and has been shown to enhance anorexia.

INFORMATION:

The new study's first author is Dr. Xing Fang, who completed graduate studies in the neurosciences at MCG and The Graduate School at AU and is now a postdoctoral scholar at the University of Southern California.

The hypothalamus is a small region -- about the size of an almond -- located just above the brainstem and involved in essentials like body temperature, blood pressure and heart rate, emotion and sleep cycles, as well as appetite and weight control.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Read the full study.

Researchers from University of Amsterdam and Stanford University published a new paper in the Journal of Marketing that examines explores how human-as-machine representations affect consumers--specifically their eating behavior and health.

The study, forthcoming in the Journal of Marketing, is titled "Portraying Humans as Machines to Promote Health: Unintended Risks, Mechanisms, and Solutions" and is authored by Andrea Weihrauch and Szu-Chi Huang.

To combat obesity, governments, marketers, and consumer welfare organizations often encourage consumers ...

Obesity and excess body fat may have contributed to more deaths in England and Scotland than smoking since 2014, according to research published in the open access journal BMC Public Health.

Between 2003 and 2017 the percentage of deaths attributable to smoking are calculated to have decreased from 23.1% to 19.4% while deaths attributable to obesity and excess body fat are calculated to have increased from 17.9% to 23.1%. The authors estimate that deaths attributable to obesity and excess body fat overtook those attributable to smoking in 2014.

Jill Pell, at the University of Glasgow, United Kingdom, the corresponding author said: "For several decades smoking has been a major target of public ...

The needs of millions of overlooked, 'left behind' adolescent women must become a more significant priority within international efforts to end poverty by 2030, a UK Government-commissioned report is urging.

The University of Cambridge report, which was commissioned by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, argues that there is an urgent need to do more to support marginalised, adolescent women in low and middle-income countries; many of whom leave education early and then face an ongoing struggle to build secure livelihoods.

Amid extensive evidence which highlights the difficulties these women face, it estimates that almost a third of adolescent ...

One third (35%) of people who took a new drug for treating obesity lost more than one-fifth (greater than or equal to 20%) of their total body weight, according to a major global study involving UCL researchers.

The findings from the large-scale international trial, published today in the New England Journal for Medicine, are being hailed as a "gamechanger" for improving the health of people with obesity and could play a major part in helping the UK to reduce the impact of diseases, such as COVID-19.

The drug, semaglutide, works by hijacking the body's own appetite regulating system in the brain leading to reduced hunger and calorie intake.

Rachel Batterham, Professor of Obesity, Diabetes and Endocrinology ...

MUSC Hollings Cancer Center researchers found that a single strain of bacteria may be able to reduce the severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), as reported online in February 2021 in JCI Insight.

Bone marrow transplant can be a lifesaving procedure for patients with blood cancers. However, GVHD is a potentially fatal side effect of transplantation, and it has limited treatment options. This proof-of-concept study demonstrates that better treatment options may be on the horizon for patients with GVHD.

Xue-Zhong Yu, M.D., associate director of Basic Science at Hollings Cancer Center, and lead ...

Researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) and their colleagues published a new analysis today in the journal Nature from genetic sequencing data of more than 53,000 individuals, primarily from minority populations. The early analysis, part of a large-scale program funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, examines one of the largest and most diverse data sets of high-quality whole genome sequencing, which makes up a person's DNA. It provides new genetic insights into heart, lung, blood and sleep disorders and how these conditions impact people with diverse racial and ...

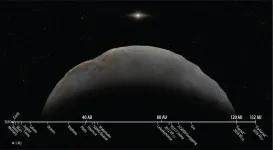

A team, including an astronomer from the University of Hawai?i Institute for Astronomy (IfA), have confirmed a planetoid that is almost four times farther from the Sun than Pluto, making it the most distant object ever observed in our solar system. The planetoid, nicknamed "Farfarout," was first detected in 2018, and the team has now collected enough observations to pin down the orbit. The Minor Planet Center has now given it the official designation of 2018 AG37.

Farfarout's name distinguished it from the previous record holder "Farout," found by the same team of astronomers in 2018. The team includes UH Mānoa's David Tholen, Scott S. Sheppard of ...

The United States spends more than $200 billion every year in efforts to treat and manage mental health. The onset of the coronavirus pandemic has only deepened the chasm for those experiencing symptoms of depression or anxiety. This breach has also widened, affecting more people.

New research from Carnegie Mellon University, University of Pittsburgh and University of California, San Diego found that 61% of surveyed university students were at risk of clinical depression, a value twice the rate prior to the pandemic. This rise in depression came alongside dramatic shifts in lifestyle habits.

The study documents dramatic changes in physical activity, sleep and time use at the onset ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- The descriptions on the fronts of infant and toddler food packages may not accurately reflect the actual ingredient amounts, according to new research. The team found that vegetables in the U.S. Department of Agriculture's "dark green" category were very likely to appear in the product name, but their average order in the ingredient list was close to fourth. In contrast, juice and juice concentrates that came earlier on the ingredient list were less likely to appear in product names.

"Early experiences with food can mold children's preferences and contribute to building healthful, or unhealthful, eating habits that last a lifetime," said author Alyssa Bakke, staff sensory scientist, Penn State. "Our previous work found combining ...

New Rochelle, NY, February 10, 2021--It may be safe for COVID-infected mothers to maintain contact with their babies. Keeping them apart can cause maternal distress and have a negative effect on exclusive breastfeeding later in infancy, according to The COVID Mothers Study published in the peer-reviewed journal Breastfeeding Medicine. Click here to read the article now.

In this worldwide study, infants who did not directly breastfeed, experience skin-to-skin care, or who did not room-in within arms' reach of their mothers were less likely to be exclusively breastfed in the first 3 months of life. Nearly 60% of ...