(Press-News.org) In research that may eventually help crops survive drought, scientists at Princeton University have uncovered a key reason that mixing material called hydrogels with soil has sometimes proven disappointing for farmers.

Hydrogel beads, tiny plastic blobs that can absorb a thousand times their weight in water, seem ideally suited to serve as tiny underground reservoirs of water. In theory, as the soil dries, hydrogels release water to hydrate plants' roots, thus alleviating droughts, conserving water, and boosting crop yields.

Yet mixing hydrogels into farmers' fields has had spotty results. Scientists have struggled to explain these uneven performances in large part because soil--being opaque --has thwarted attempts at observing, analyzing, and ultimately improving hydrogel behaviors.

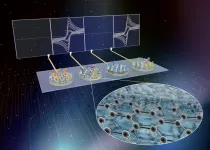

In a new study, the Princeton researchers demonstrated an experimental platform that allows scientists to study the hydrogels' hidden workings in soils, along with other compressed, confined environments. The platform relies on two ingredients: a transparent granular medium--namely a packing of glass beads--as a soil stand-in, and water doped with a chemical called ammonium thiocyanate. The chemical cleverly changes the way the water bends light, offsetting the distorting effects the round glass beads would ordinarily have. The upshot is that researchers can see straight through to a colored hydrogel glob amidst the faux soil.

"A specialty of my lab is finding the right chemical in the right concentrations to change the optical properties of fluids," said Sujit Datta, an assistant professor of chemical and biological engineering at Princeton and senior author of the study appearing in the journal

Science Advances on Feb. 12. "This capability enables 3D visualization of fluid flows and other processes that occur within normally inaccessible, opaque media, such as soil and rocks."

The scientists used the setup to demonstrate that the amount of water stored by hydrogels is controlled by a balance between the force applied as the hydrogel swells with water and the confining force of the surrounding soil. As a result, softer hydrogels absorb large quantities of water when mixed into surface layers of soil, but don't work as well in deeper layers of soil, where they experience a larger pressure. Instead, hydrogels that have been synthesized to have more internal crosslinks, and as a result are stiffer and can exert a larger force on the soil as they absorb water, would be more effective in deeper layers. Datta said that, guided by these results, engineers will now be able to conduct further experiments to tailor the chemistry of hydrogels for specific crops and soil conditions.

"Our results provide guidelines for designing hydrogels that can optimally absorb water depending on the soil they are meant to be used in, potentially helping to address growing demands for food and water," said Datta.

The inspiration for the study came from Datta learning about the immense promise of hydrogels in agriculture but also their failure to meet it in some cases. Seeking to develop a platform to investigate hydrogel behavior in soils, Datta and colleagues started with a faux soil of borosilicate glass beads, commonly used for various bioscience investigations and, in everyday life, costume jewelry. The bead sizes ranged from one to three millimeters in diameter, consistent with the grain sizes of loose, unpacked soil.

In summer 2018, Datta assigned Margaret O'Connell, then a Princeton undergraduate student working in his lab through Princeton's ReMatch+ program, to identify additives that would change water's refractive index to offset the beads' light distortion, yet still allow a hydrogel to effectively absorb water. O'Connell alit upon an aqueous solution with a bit over half of its weight contributed by ammonium thiocyanate.

Nancy Lu, a graduate student at Princeton, and Jeremy Cho, then a postdoc in Datta's lab and now an assistant professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, built a preliminary version of the experimental platform. They placed a colored hydrogel sphere, made from a conventional hydrogel material called polyacrylamide, amidst the beads and gathered some initial observations.

Jean-Francois Louf, a postdoctoral researcher in Datta's lab, then constructed a second, honed version of the platform and performed the experiments whose results were reported in the study. This final platform included a weighted piston to generate pressure on top of the beads, simulating a range of pressures a hydrogel would encounter in soil, depending upon how deep the hydrogel is implanted.

Overall, the results showed the interplay between hydrogels and soils, based on their respective properties. A theoretical framework the team developed to capture this behavior will help in explaining the confounding field results gathered by other researchers, where sometimes crop yields improved, but other times hydrogels showed minimal benefits or even degraded the soil's natural compaction, increasing the risk of erosion.

Ruben Juanes, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who was not involved in the study, offered comments on its significance. "This work opens up tantalizing opportunities for the use of hydrogels as soil capacitors that modulate water availability and control water release to crop roots, in a way that could provide a true technological advance in sustainable agriculture," said Juanes.

Other applications of hydrogels stand to gain from Datta and his colleagues' work. Example areas include oil recovery, filtration, and the development new kinds of building materials, such as concrete infused with hydrogels to prevent excessive drying out and cracking. One particularly promising area is biomedicine, with applications ranging from drug delivery to wound healing and artificial tissue engineering.

"Hydrogels are a really cool, versatile material that also happen to be fun to work with," said Datta. "But while most lab studies focus on them in unconfined settings, many applications involve their use in tight and confined spaces. We're very excited about this simple experimental platform because it is allowing us to see what other people couldn't see before."

The work was supported in part by the National Science Foundation and the High Meadows Environmental Institute at Princeton.

INFORMATION:

COVID-19 vaccine prioritization should prioritize those with advanced cardiovascular (CVD) disease over well-managed CVD disease, according to an American College of Cardiology (ACC) health policy statement published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC). All CVD patients face a higher risk of COVID-19 complications and should receive the vaccine quickly, but recommendations in this paper serve to guide clinicians in prioritizing their most vulnerable patients within the larger CVD group, while considering disparities in COVID-19 outcomes among different racial/ethnic groups and socioeconomic ...

A new type of drug that helps target chemotherapy directly to cancer cells has been found to significantly increase survival of patients with the most common form of bladder cancer, according to results from a phase III clinical trial led in the UK by Queen Mary University of London and Barts Health NHS Trust.

The results are published in the New England Journal of Medicine and were presented at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology's Genitourinary Cancers Symposium.

Urothelial cancer is the most common type of bladder cancer (90 percent of cases) and can also be found in the renal pelvis (where urine collects inside the kidney), ureter (tube that connects the kidneys ...

WORCESTER, Mass. -- New research by Christopher A. Williams, an environmental scientist and professor in Clark University's Graduate School of Geography, reveals that deforestation in the U.S. does not always cause planetary warming, as is commonly assumed; instead, in some places, it actually cools the planet. A peer-reviewed study by Williams and his team, "Climate Impacts of U.S. Forest Loss Span Net Warming to Net Cooling," published today (Feb. 12) in Science Advances. The team's discovery has important implications for policy and management efforts that are turning to forests to mitigate climate change.

It ...

RIVERSIDE, Calif. -- Astrocytes -- star-shaped cells in the brain that are actively involved in brain function -- may play an important role in stuttering, a study led by a University of California, Riverside, expert on stuttering has found.

"Our study suggests that treatment with the medication risperidone leads to increased activity of the striatum in persons who stutter," said Dr. END ...

HANOVER, N.H. - February 12, 2021 - A newly discovered planetary system will provide researchers with the rare chance to study a group of growing planets, according to research co-led by Dartmouth.

The new system, named TOI 451, is made up of at least three neighboring planets that orbit the same sun. The planets range in size between that of Earth and Neptune.

According to the research team, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and its planned successor, the James Webb Space Telescope, can be used to study the atmosphere of each planet. Such research could lead to information on how planetary systems like our own solar system evolve.

"The sun in this planetary system is very similar to our own sun, but much younger," ...

In your quest for true love and that elusive happily ever after, are you waiting for the "right" person to come along, or do you find yourself going for the cutest guy or girl in the room, hoping things will work out? Do you leave your options open, hoping to "trade-up" at the next opportunity, or do you invest in your relationship with an eye on the cost-benefits analysis?

For something so fundamental to our existence, mate selection remains one of humanity's most enduring mysteries. It's been the topic of intense psychological research for decades, spawning myriad hypotheses of why we choose whom we choose.

"Mate choice is really complicated, especially in humans," ...

CHICAGO (February 12, 2021): Since 2010, National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding to support surgeon scientists has, remarkably, risen significantly while funding to support other non-surgeon physicians has significantly decreased. This growth has occurred despite an overall decrease in NIH funding and an increase in demand for clinical productivity. These findings are according to an " END ...

Scientists at Lund University have discovered how E. coli bacteria target and degrade the well-known oncogene MYC, which is involved in many forms of cancer. The study is now published in Nature Biotechnology.

Cancer cells grow too fast, outcompete normal cells and spread to distant sites, where they cause metastases. Understanding what makes cancer cells so efficient and threatening is critically important and stopping them has always been the goal of cancer research. Early studies identified so-called ''oncogenes''; genes that that normally control cell growth but when mutated may be responsible for the creation of cancer cells and explain their competitive advantage.

The pleiotropic transcription factor MYC has been ...

(BOSTON) -- Many life-threatening medical conditions, such as sepsis, which is triggered by blood-borne pathogens, cannot be detected accurately and quickly enough to initiate the right course of treatment. In patients that have been infected by an unknown pathogen and progress to overt sepsis, every additional hour that an effective antibiotic cannot be administered significantly increases the mortality rate, so time is of utmost essence.

The challenge with rapidly diagnosing sepsis stems from the fact that measuring only one biomarker often does not allow a clear-cut diagnosis. Engineers have struggled for decades to simultaneously quantify multiple biomarkers in whole blood with high ...

The drug thalidomide was sold as a sedative under the trade name Contergan in the 1950s and 1960s. At the time, its side-effects triggered one of the largest pharmaceutical scandals in history: The medication was taken from the market after it became known that the use of Contergan during pregnancy had resulted in over 10,000 cases of severe birth defects.

Currently, the successor preparations lenalidomide and pomalidomide are prescribed under strict supervision by experienced oncologists - the active ingredients are a cornerstone of modern cancer therapies. The use of lenalidomide and pomalidomide has considerably improved the success ...