(Press-News.org) A new paper refines estimates of when herbivorous dinosaurs must have traversed North America on a northerly trek to reach Greenland, and points out an intriguing climatic phenomenon that may have helped them along the journey.

The study, published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is authored by Dennis Kent, adjunct research scientist at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and Lars Clemmensen from the University of Copenhagen.

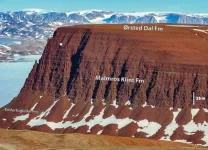

Previous estimates suggested that sauropodomorphs -- a group of long-necked, herbivorous dinosaurs that eventually included Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus -- arrived in Greenland sometime between 225 and 205 million years ago. But by painstakingly matching up ancient magnetism patterns in rock layers at fossil sites across South America, Arizona, New Jersey, Europe and Greenland, the new study offers a more precise estimate: It suggests that sauropodomorphs showed up in what is now Greenland around 214 million years ago. At the time, the continents were all joined together, forming the supercontinent Pangea.

With this new and more precise estimate, the authors faced another question. Fossil records show that sauropodomorph dinosaurs first appeared in Argentina and Brazil about 230 million years ago. So why did it take them so long to expand into the Northern Hemisphere?

"In principle, the dinosaurs could have walked from almost one pole to the other," explained Kent. "There was no ocean in between. There were no big mountains. And yet it took 15 million years. It's as if snails could have done it faster." He calculates that if a dinosaur herd walked only one mile per day, it would take less than 20 years to make the journey between South America and Greenland.

Intriguingly, Earth was in the midst of a tremendous dip in atmospheric CO2 right around the time the sauropodomorphs would have been migrating 214 million years ago. Until about 215 million years ago, the Triassic period had experienced extremely high CO2 levels, at around 4,000 parts per million -- about 10 times higher than today. But between 215 and 212 million years ago, the CO2 concentration halved, dropping to about 2,000ppm.

Although the timing of these two events -- the plummeting CO2 and the sauropodomorph migration -- could be pure coincidence, Kent and Clemmensen think they may be related. In the paper, they suggest that the milder levels of CO2 may have helped to remove climatic barriers that may have trapped the sauropodomorphs in South America.

On Earth, areas around the equator are hot and humid, while adjacent areas in low latitudes tend to be very dry. Kent and Clemmensen say that on a planet supercharged with CO2, the differences between those climatic belts may have been extreme -- perhaps too extreme for the sauropodomorph dinosaurs to cross.

"We know that with higher CO2, the dry gets drier and the wet gets wetter," said Kent. 230 million years ago, the high CO2 conditions could have made the arid belts too dry to support the movements of large herbivores that need to eat a lot of vegetation to survive. The tropics, too, may have been locked into rainy, monsoon-like conditions that may not have been ideal for sauropodomorphs. There is little evidence they ventured forth from the temperate, mid-latitude habitats they were adapted to in Argentina and Brazil.

But when the CO2 levels dipped 215-212 million years ago, perhaps the tropical regions became more mild, and the arid regions became less dry. There may have been some passageways, such as along rivers and strings of lakes, that would have helped sustain the herbivores along the 6,500-mile journey to Greenland, where their fossils are now abundant. Back then, Greenland would have had a temperate climate similar to New York state's climate today, but with much milder winters, because there were no polar ice sheets at that time.

"Once they arrived in Greenland, it looked like they settled in,'" said Kent. "They hung around as a long fossil record after that."

The idea that a dip in CO2 could have helped these dinosaurs to overcome a climatic barrier is speculative but plausible, and it seems to be supported by the fossil record, said Kent. Sauropodomorph body fossils have not been found in the tropical and arid regions of this time period -- although their footprints do occasionally turn up -- suggesting they did not linger in those areas.

Next, Kent hopes to continue working to better understand the big CO2 dip, including what caused it and how quickly CO2 levels dropped.

INFORMATION:

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory is Columbia University's home for Earth science research. Its scientists develop fundamental knowledge about the origin, evolution and future of the natural world, from the planet's deepest interior to the outer reaches of its atmosphere, on every continent and in every ocean, providing a rational basis for the difficult choices facing humanity. http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu | @LamontEarth

The Earth Institute, Columbia University mobilizes the sciences, education and public policy to achieve a sustainable earth. http://www.earth.columbia.edu.

Experts have devised a novel approach to selecting photos for police lineups that helps witnesses identify culprits more reliably.

In a paper published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers - from the University of California San Diego and Duke University in the United States and the University of Birmingham in the U.K. - show for the first time that selecting fillers who match a basic description of the suspect but whose faces are less similar, rather than more, leads to better outcomes than traditional approaches in the field.

The counterintuitive technique improves eyewitness performance by about 10 percent.

"In ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- MIT researchers have invented a new type of amputation surgery that can help amputees to better control their residual muscles and sense where their "phantom limb" is in space. This restored sense of proprioception should translate to better control of prosthetic limbs, as well as a reduction of limb pain, the researchers say.

In most amputations, muscle pairs that control the affected joints, such as elbows or ankles, are severed. However, the MIT team has found that reconnecting these muscle pairs, allowing them to retain their normal push-pull ...

The threat of landslides is again in the news as torrential winter storms in California threaten to undermine fire-scarred hillsides and bring deadly debris flows crashing into homes and inundating roads.

But it doesn't take wildfires to reveal the landslide danger, University of California, Berkeley, researchers say. Aerial surveys using airborne laser mapping -- LiDAR (light detection and ranging) -- can provide very detailed information on the topography and vegetation that allow scientists to identify which landslide-prone areas could give way during an expected rainstorm. This is especially ...

More than one-third of the Corn Belt in the Midwest - nearly 100 million acres - has completely lost its carbon-rich topsoil, according to University of Massachusetts Amherst research that indicates the U.S. Department of Agricultural has significantly underestimated the true magnitude of farmland erosion.

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers led by UMass Amherst graduate student Evan Thaler, along with professors Isaac Larsen and Qian Yu in the department of geosciences, developed a method using satellite ...

The links between cardiovascular disease and cognitive impairment begin years before the appearance of the first clinical symptoms of either condition. In a study carried out at the Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC) in partnership with Santander Bank and neuroimaging experts at the Barcelonaβeta Brain Research Center (BBRC, the research center of the Fundación Pasqual Maragall), the investigators have identified a link between brain metabolism, cardiovascular risk, and atherosclerosis during middle age, years before the first appearance of symptoms.

The report, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC), ...

Employing cardiovascular disease prevention strategies in mid-life may delay or stop the brain alterations that can lead to dementia later in life, according to a study in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Atherosclerosis, or buildup of fats, cholesterol and other substances in and on artery walls, is the underlying cause of most cardiovascular diseases, which is the leading cause of death around the world. Dementia is also among the top causes of death and disability around the world, with 50 million people currently living with dementia. ...

In a new study out of University of California San Diego School of Medicine, researchers found a drug used for heart failure improves symptoms associated with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, otherwise known as POTS. This complex, debilitating disorder affects the body's autonomic nervous system, causing a high heart rate, usually when standing.

Writing in the February 15, 2021 online issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, study authors investigated the drug ivabradine and its effects on heart rate, quality of life and plasma norepinephrine levels in persons living with POTS. Norepinephrine is a stress hormone and neurotransmitter. In blood plasma, it is used as a measure of sympathetic nervous system activity. Trial participants experienced a reduction in ...

Young men with lower testosterone levels throughout puberty become more sensitive to how the hormone influences the brain's responses to faces in adulthood, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

During prenatal brain development, sex hormones like testosterone organize the brain in permanent ways. But research suggests that testosterone levels during another developmental period -- puberty -- may have long-lasting effects on brain function, too.

Liao et al. examined the relationship between puberty testosterone levels and the brain's response to faces. Liao's team recruited 500 men around age 19 who had been participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and ...

PITTSBURGH, Feb. 15, 2021 - By capitalizing on a convergence of chemical, biological and artificial intelligence advances, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine scientists have developed an unusually fast and efficient method for discovering tiny antibody fragments with big potential for development into therapeutics against deadly diseases.

The technique, published today in the journal Cell Systems, is the same process the Pitt team used to extract tiny SARS-CoV-2 antibody fragments from llamas, which could become an inhalable COVID-19 treatment for humans. This approach has the potential to quickly identify multiple potent nanobodies that target different parts of a pathogen--thwarting ...

What The Study Did: Data from four studies of children and adolescents exposed to major U.S. hurricanes were pooled to examine posttraumatic stress symptoms after those events and the factors associated with them.

Authors: Betty S. Lai, Ph.D., of Boston College in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.36682)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article ...