(Press-News.org) Mammals and cold-blooded alligators share a common four-chamber heart structure - unique among reptiles - but that's where the similarities end. Unlike humans and other mammals, whose hearts can fibrillate under stress, alligators have built-in antiarrhythmic protection. The findings from new research were reported Jan. 27 in the journal Integrative Organismal Biology.

"Alligator hearts don't fibrillate - no matter what we do. They're very resilient," said Flavio Fenton, a professor in the School of Physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology, researcher in the Petit Institute for Bioengineering and Bioscience, and the report's corresponding author. Fibrillation is one of the most dangerous arrhythmias, leading to blood clots and stroke when occurring in the atria and to death within minutes when it happens in the ventricles.

The study looked at the action potential wavelengths of rabbit and young alligator hearts. Both species have four-chambered hearts of similar size (about 3 cm); however, while rabbits maintain a constant heart temperature of 38 degrees Celsius, the body temperature of active, wild alligators ranges from 10 to 37 degrees Celsius. Heart pumping is controlled by an electrical wave that tells the muscle cells to contract. An electrical signal drives this wave, which must occur in the same pattern to keep blood pumping normally. In a deadly arrhythmia, this electrical signal is no longer coherent.

"An arrhythmia can happen for many reasons, including temperature dropping. For example, if someone falls into cold water and gets hypothermia, very often this person will develop an arrythmia and then drown," Fenton said.

During the study, the researchers recorded changes in the heart wave patterns at 38 C and 23 C. "The excitation wave in the rabbit heart reduced by more than half during temperature extremes while the alligator heart showed changes of only about 10% at most," said Conner Herndon, a co-author and a graduate research assistant in the School of Physics. "We found that when the spatial wavelength reaches the size of the heart, the rabbit can undergo spontaneous fibrillation, but the alligator would always maintain this wavelength within a safe regime," he added.

While alligators can function over a large temperature range without risk of heart trauma, their built-in safeguard has a drawback: it limits their maximum heart rate, making them unable to expend extra energy in an emergency.

Rabbits and other warm-blooded mammals, on the other hand, can accommodate higher heart rates necessary to sustain an active, endothermic metabolism but they face increased risk of cardiac arrhythmia and critical vulnerability to temperature changes.

The physicists from Georgia Tech collaborated with two biologists on the study, including former Georgia Tech postdoctoral fellow Henry Astley, now assistant professor in the Biomimicry Research and Innovation Center at the University of Akron's Department of Biology.

"I was a little surprised by how massive the difference was - the sheer resilience of the crocodilian heart and the fragility of the rabbit heart. I had not expected the rabbit heart to come apart at the seams as easily as it did," noted Astley.

Lower temperatures are one cause of cardiac electrophysiological arrhythmias, where fast-rotating electrical waves can cause the heart to beat faster and faster, leading to compromised cardiac function and potentially sudden cardiac death. Lowering the temperature of the body - frequently done for patients before certain surgeries - also can induce an arrhythmia.

The researchers agree that this study could help better understand how the heart works and what can cause a deadly arrhythmia - which fundamentally happens when the heart doesn't pump blood correctly any longer.

The authors also consider the research a promising step toward better understanding of heart electrophysiology and how to help minimize fibrillation risk. Until December 2020, when Covid-19 took the top spot, heart disease was the leading cause of death in the United States and in most industrialized countries, with more people dying of heart disease than the next two causes of death combined.

Astley said the research provides a deeper understanding of the natural world and insight into the different coping mechanisms of cold- and warm-blooded animals.

Co-author Tomasz Owerkowicz, associate professor in the Department of Biology at California State University, San Bernardino, considers the findings "another piece of the puzzle that helps us realize how really cool non-human animals are and how many different tricks they have up their sleeves."

He expressed hope that more researchers will follow their example and use a non-traditional animal model in future research.

"Everyone studies mammals, fruit flies, and zebrafish. There's such a huge wealth of resources among the wild animals that have not been brought to the laboratory setting that have such neat physiologies, that are waiting to be uncovered. All we have to do is look," he said.

INFORMATION:

CITATION: C. Herndon, et al., "Defibrillate you Later, Alligator; Q10 Scaling and Refractoriness Keeps Alligators from Fibrillation." (Integrative Organismal Biology, 2021) https://academic.oup.com/iob/advance-article/doi/10.1093/iob/obaa047/6120966?login=true

COLUMBIA, Mo. -- Throughout her career, Lori Popejoy provided hands-on clinical care in a variety of health care settings, from hospitals and nursing homes to community centers and home health care agencies. She became interested in the area of care coordination, as patients who are not properly cared for after being discharged from the hospital often end up being readmitted in a sicker, more vulnerable state of health.

Now an associate professor in the University of Missouri Sinclair School of Nursing, Popejoy and her research team conducted a study to determine the most effective way patients ...

Metabolic diseases, such as obesity and type 2 diabetes, have risen to epidemic proportions in the U.S. and occur in about 30 percent of the population. Skeletal muscle plays a prominent role in controlling the body's glucose levels, which is important for the development of metabolic diseases like diabetes.

In a recent study, published in END ...

Investigators at the University of Chicago Medicine have found that women are less likely to be represented as chairs and reviewers on study sections for the National Institutes of Health (NIH), based on data from one review cycle in 2019. The results, published on Feb. 15 in JAMA Network Open, have implications for the distribution of federal scientific funding.

The NIH is the top source of federal funding for biomedical research in the U.S., providing critical support and guidance on the nation's research programs. The study sought to understand the gender distribution ...

New research from North Carolina State University has found that Campylobacter bacteria persist throughout poultry production - from farm to grocery shelves - and that two of the most common strains are exchanging genetic material, which could result in more antibiotic-resistant and infectious Campylobacter strains.

Campylobacter is a well-known group of foodborne bacteria, spread primarily through consumption of contaminated food products. In humans it causes symptoms commonly associated with food poisoning, such as diarrhea, fever and cramps. However, Campylobacter infections also constitute one of the leading precursors ...

Surface rupturing during earthquakes is a significant risk to any structure that is built across a fault zone that may be active, in addition to any risk from ground shaking. Surface rupture can affect large areas of land, and it can damage all structures in the vicinity of the fracture. Although current seismic codes restrict the construction in the vicinity of active tectonic faults, finding the exact location of fault outcrop is often difficult.

In many regions around the world, engineering structures such as earth dams, buildings, pipelines, landfills, bridges, roads and railroads have been built in areas very close to active fault segments. Strike-slip fault rupture occurs when the rock masses slip past each other ...

Cancer cells and immune cells share something in common: They both love sugar.

Sugar is an important nutrient. All cells use sugar as a vital source of energy and building blocks. For immune cells, gobbling up sugar is a good thing, since it means getting enough nutrients to grow and divide for stronger immune responses. But cancer cells use sugar for more nefarious ends.

So, what happens when tumor cells and immune cells battle for access to the same supply of sugar? That's the central question that Memorial Sloan Kettering researchers Taha Merghoub, Jedd Wolchok, and Roberta Zappasodi explore in a new study published February 15 in the journal Nature.

Using mouse models and data ...

Ithaca, NY--The COVID-19 pandemic has changed life as we know it all around the world. It's changed human behavior, and that has major consequences for data-gathering citizen-science projects such as eBird, run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. This worldwide database now contains more than a billion observations and is a mainstay of many scientific studies of bird populations. Newly published research in the journal Biological Conservation finds that when human behaviors change, so do the data.

"We examined eBird data submitted during April 2020 and compared them to data from April of prior years," explains lead ...

Researchers from the UCLA School of Dentistry have identified the role a critical enzyme plays in skeletal aging and bone loss, putting them one step closer to understanding the complex biological mechanisms that lead to osteoporosis, the bone disease that afflicts some 200 million people worldwide.

The findings from their study in mice, END ...

New Edith Cowan University (ECU) research has found that exercise not only has physical benefits for men with prostate cancer, it also helps reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Up to one in four men experience anxiety either before or after prostate cancer treatment and up to one in five report depression, although few men access the support they need.

The study, published in the Nature journal Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases, is the first randomised controlled trial to examine the long-term effects of different exercise on psychological distress in men with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).

Researchers randomly selected 135 prostate cancer patients aged ...

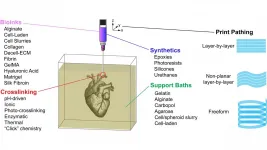

WASHINGTON, February 16, 2021 -- Research into 3D bioprinting has grown rapidly in recent years as scientists seek to re-create the structure and function of complex biological systems from human tissues to entire organs.

The most popular 3D printing approach uses a solution of biological material or bioink that is loaded into a syringe pump extruder and deposited in a layer-by-layer fashion to build the 3D object. Gravity, however, can distort the soft and liquid bioinks used in this method.

In APL Bioengineering, by AIP Publishing, researchers from Carnegie Mellon University provide perspective on the Freefrom Reversible Embedding of Suspended Hydrogels ...