(Press-News.org) After seven years of intense research, a research group from Aarhus University has succeeded - through an interdisciplinary collaboration - in understanding why a very extended structure is important for an essential protein from the human immune system. The new results offer new opportunities for adjusting the activity of the immune system both up and down. Stimulation is interesting in relation to cancer treatment, while inhibition of the immune system is used in treatment of autoimmune diseases.

In our bloodstream and tissues, the complement system acts as one of the very first defense mechanisms against pathogenic organisms. When these are detected by the complement system, a chain reaction starts, which ends with the pathogen being eliminated and other parts of the immune system being stimulated. The protein properdin is crucial for the efficiency of the complement system. Fortunately, we almost all have sufficient properdin, as otherwise, we are at risk of dying as a child from infectious diseases.

In 2013, Professor Gregers Rom Andersen from the Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics at Aarhus University was frustrated to know many details about other proteins in the complement system, but properdin seemed to be too difficult to work with. It was known that the protein had a very extended structure, which would make it almost impossible to determine the three-dimensional structure of properdin. To make matters worse, properdin is present in three different forms within the body, so-called oligomers, which contain two, three or four copies of the protein.

"But fortunately, Dennis Vestergaard Pedersen walked in the door in the autumn of 2013 to start as a PhD student. Actually, he only had to work with properdin as a side project as it was too risky. But, one day we sketched on the back of an envelope how one might be able to cut properdin into smaller pieces. It worked surprisingly well," says Gregers Rom Andersen.

In this way, Dennis determined the crystal structure of the individual pieces of a properdin molecule after five years. By then, Dennis had long since finished his PhD and did contract research at Aarhus University. But one thing bothered Dennis.

"Despite five years of work, I still did not know what the properdin oligomers we have in our body look like and what role their unusual and extended structure plays for the function of properdin," says Dennis Vestergaard Pedersen.

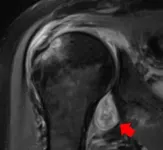

"I started for fun studying one of the three properdin oligomers using electron microscopy. To my great surprise, I discovered that this properdin oligomer is a rigid molecule, and not flexible as I had expected. This was a big surprise, and really whet my appetite," Dennis continues.

"In collaboration with colleagues at the University of Copenhagen, I therefore started to study the various properdin oligomers in detail. We combined electron microscopy and a technique called small angle scattering, and we were thus able to prove that all the different properdin oligomers are rigid, spatially well-defined molecules."

The special extended structure of properdin is important for the function of the protein in the immune system

At the same time, Dennis - along with Master thesis student Sofia MM Mazarakis - conducted laboratory experiments comparing the ability of artificial and naturally occurring properdin oligomers to drive the activation of the complement system. By combining these data with structural data, the researchers were able to show that the special extended structure of properdin actually is important for the function of the protein in the immune system.

Gregers Rom Andersen elaborates: "Dennis' long and persistent work with properdin has given us a whole new understanding of "the molecule from hell" and especially why it looks the way it does. It has given us new opportunities in terms of being able to control the activity of the complement system both up and down. Stimulation is interesting in connection with cancer, while shutdown of the complement is already used to treat autoimmune diseases."

Through his long work with properdin, Dennis has for a long time collaborated with a large pharmaceutical company and will now try to develop medicine himself. Together with three other researchers from Aarhus University, Dennis has developed a technique that takes advantage of our body's own complement system to kill cancer cells. The technique has just been patented by Aarhus University, and the researchers are now further developing the technique with support from the Innovation Fund Denmark and the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

INFORMATION:

The researchers' work with properdin was supported financially by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation.

The research results have just been published in the prestigious scientific journal eLife:

"Properdin oligomers adopt rigid extended conformations supporting function"

Dennis V Pedersen, Martin Nors Pedersen, Sofia MM Mazarakis, Yong Wang, Kresten Lindorff-Larsen, Lise Arleth, Gregers R Andersen

https://elifesciences.org/articles/63356

DOI: 10.7554/eLife.63356

People with asthma in the most deprived areas are 50% more likely to be admitted to hospital and to die from asthma compared with those in the least deprived areas, a new five-year study of over 100,000 people in Wales has revealed.

Those from more deprived backgrounds were also found to have a poor balance of essential asthma medications that help prevent asthma attacks.

The new research, published in the journal PLOS Medicine, was conducted by Swansea University's Wales Asthma Observatory in collaboration with Asthma UK Centre for Applied Research and Liverpool University, and found ...

SAN FRANCISCO, CA--February 16, 2021--In people with central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma, cancerous B cells--a type of white blood cell--accumulate to form tumors in the brain or spinal cord, often in close proximity to blood vessels. This disease is quite rare, but individuals who are affected have limited treatment options and often experience recurrence.

Previous research has linked the severity of CNS lymphoma to abnormal leaks in the blood-brain barrier, a protective system that allows some substances to pass from the bloodstream to the brain, while blocking others. However, the specific molecular details of this link have been murky.

Now, Gladstone researchers have ...

Tsukuba, Japan - It's tough out there in the sea, as the widespread loss of complex marine communities is testament to. Researchers from Japan have discovered that ocean acidification favors degraded turf algal systems over corals and other algae, thanks to the help of feedback loops.

In a study published this month in Communications Biology, researchers from the University of Tsukuba have revealed that ocean acidification and feedback loops stabilize degraded turf algal systems, limiting the recruitment of coral and other algae.

Oceans are undergoing widespread changes as a result of human activities. These changes take the form of regime shifts - major, sudden and persistent changes in ecosystem structure and function. An example is the replacement of coral reefs and kelp ...

An estimated 1.1 billion people were living with untreated vision impairment in 2020, but researchers say more than 90 per cent of vision loss could be prevented or treated with existing, highly cost-effective interventions.

Published today in The Lancet Global Health, a new commission report on global eye health calls for eye care to be included in mainstream health services and development policies. It argues that this is essential to achieve the WHO goal of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Written by 73 leading experts from 25 countries, including University of ...

FEBRUARY 15, 2021, NEW YORK - A Ludwig Cancer Research study has identified a novel mechanism by which a type of cancer immunotherapy known as CTLA-4 blockade can disable suppressive immune cells to aid the destruction of certain tumors. The tumors in question are relatively less reliant on burning sugar through a biochemical process known as glycolysis.

Researchers led by Taha Merghoub and Jedd Wolchok of the Ludwig Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and former postdoc Roberta Zappasodi--now at Weill Cornell Medicine--have discovered that in a mouse model of glycolysis-deficient tumors, CTLA-4 blockade does ...

Durham, NC- Can stem cells alleviate lymphedema, a chronic debilitating condition affecting up to one in three women treated for breast cancer? Results of a phase I clinical trial released today in STEM CELLS Translational Medicine (SCTM) show there is a strong possibility that the answer is yes.

Lymphedema is swelling due to a build-up of fluid in lymph nodes - vessels that help rid the body of toxins, waste, and other unwanted materials- usually occurring in an arm or leg. While it can be the result of an inherited condition, its most common cause in the Western world is the removal of or damage to the lymph nodes during the course of cancer ...

CHICAGO --- Muscle soreness and achy joints are common symptoms among COVID-19 patients. But for some people, symptoms are more severe, long lasting and even bizarre, including rheumatoid arthritis flares, autoimmune myositis or "COVID toes."

A new Northwestern Medicine study has, for the first time, confirmed and illustrated the causes of these symptoms through radiological imaging.

"We've realized that the COVID virus can trigger the body to attack itself in different ways, which may lead to rheumatological issues that require lifelong management," said corresponding author Dr. Swati Deshmukh.

The paper will be published Feb. 17 in the journal Skeletal Radiology. The study is a retrospective review of data from patients who presented to Northwestern Memorial Hospital between ...

A woman's body shape--not only the amount of fat--is what drives stigma associated with overweight and obesity.

Fat stigma is a socially acceptable form of prejudice that contributes to poor medical outcomes and negatively affects educational and economic opportunities. But a new study has found that not all overweight and obese body shapes are equally stigmatized. Scientists from Arizona State University and Oklahoma State University have shown that women with abdominal fat around their midsection are more stigmatized than those with gluteofemoral fat on the hips, buttocks and thighs. The work will be published on February 17 in Social Psychology and Personality Science.

"Fat stigma is pervasive, painful and results ...

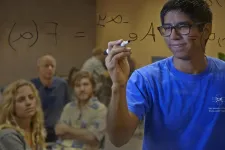

To provoke more interest and excitement for students and lecturers alike, a professor from Florida Atlantic University's College of Engineering and Computer Science is spicing up the study of complex differential mathematical equations using relevant history of algebra. In a paper published in the Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Isaac Elishakoff, Ph.D., provides a refreshing perspective and a special "shout out" to Stephen Colbert, comedian and host of CBS's The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. His motivation? Colbert previously referred to mathematical equations as ...

Children are protected from severe COVID-19 because their innate immune system is quick to attack the virus, a new study has found.

The research led by the Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) and published in Nature Communications, found that specialised cells in a child's immune system rapidly target the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

MCRI's Dr Melanie Neeland said the reasons why children have mild COVID-19 disease compared to adults, and the immune mechanisms underpinning this protection, were unknown until this study.

"Children are less likely to become infected with the virus and up to a third are asymptomatic, which is strikingly different to ...