Body shape, beyond weight, drives fat stigma for women

2021-02-17

(Press-News.org) A woman's body shape--not only the amount of fat--is what drives stigma associated with overweight and obesity.

Fat stigma is a socially acceptable form of prejudice that contributes to poor medical outcomes and negatively affects educational and economic opportunities. But a new study has found that not all overweight and obese body shapes are equally stigmatized. Scientists from Arizona State University and Oklahoma State University have shown that women with abdominal fat around their midsection are more stigmatized than those with gluteofemoral fat on the hips, buttocks and thighs. The work will be published on February 17 in Social Psychology and Personality Science.

"Fat stigma is pervasive, painful and results in huge mental and physical health costs for individuals," said Jaimie Arona Krems, assistant professor of psychology at OSU and first author on the paper. "We found that even when women are the same height and weight, they were stigmatized differently--and this was driven by whether they carried abdominal or gluteofemoral fat. Indeed, in one case, people stigmatized obese women with gluteofemoral fat more than objectively smaller women with abdominal fat. This finding suggests that body shape is sometimes even more important than overall size in driving fat stigma."

The location of fat on the body determines body shape and is associated with different biological functions and health outcomes. Gluteofemoral fat in young women can indicate fertility, while abdominal fat can accompany negative health outcomes like diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

"When people try to understand what others are like, and what characteristics they possess, they often rely on easily visible cues to make their best guesses. We've known for a long time that people use weight as such a cue. Given that different fats, on different parts of the body, are associated with different outcomes, we wanted to explore whether people also systematically use body shape as a cue," said Steven Neuberg, co-author of the study and Foundation Professor and Chair of the ASU Department of Psychology.

To test how the location of fat on the body affected stigma, the research team created illustrations of underweight, average-weight, overweight and obese bodies that varied in both size and shape. The illustrations of higher-weight bodies had either gluteofemoral or abdominal fat.

The study participants stigmatized obese women more than overweight women and also overweight women more than average-weight women. But women with overweight who weighed the same were less stigmatized when they carried gluteofemoral fat than when they carried abdominal fat. This same pattern held for women with obesity, suggesting that body shape, in addition to overall body size, drives stigmatization.

The research team also tested the impact of body shape in driving stigma in different ethnicities and cultures. White and Black Americans, and also participants in India, all showed the same pattern of stigmatizing women carrying abdominal fat.

"The findings from this study are probably not surprising to most women, who have long talked about the importance of shape, or to anyone who has read a magazine article on 'dressing for your shape' that categorizes body shapes as apples, pears, hourglasses and the like," Krems said. "Because theories have not focused on body shape, we haven't tested for its importance and have missed one of the major drivers of fat stigma for some time. It is important to put data to this idea so we can improve interventions for people with overweight and obesity."

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-17

To provoke more interest and excitement for students and lecturers alike, a professor from Florida Atlantic University's College of Engineering and Computer Science is spicing up the study of complex differential mathematical equations using relevant history of algebra. In a paper published in the Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Isaac Elishakoff, Ph.D., provides a refreshing perspective and a special "shout out" to Stephen Colbert, comedian and host of CBS's The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. His motivation? Colbert previously referred to mathematical equations as ...

2021-02-17

Children are protected from severe COVID-19 because their innate immune system is quick to attack the virus, a new study has found.

The research led by the Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) and published in Nature Communications, found that specialised cells in a child's immune system rapidly target the new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2).

MCRI's Dr Melanie Neeland said the reasons why children have mild COVID-19 disease compared to adults, and the immune mechanisms underpinning this protection, were unknown until this study.

"Children are less likely to become infected with the virus and up to a third are asymptomatic, which is strikingly different to ...

2021-02-17

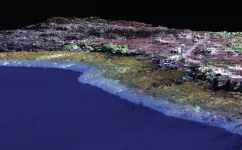

A new study, published in Bioscience, considers the future of ecology, where technological advancement towards a multidimensional science will continue to fundamentally shift the way we view, explore, and conceptualize the natural world.

The study, co-led by Greg Asner, Director of the Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, in collaboration with Auburn University, the Oxford Seascape Ecology Lab, and other partners, demonstrates how the integration of remotely sensed 3D information holds great potential to provide new ecological insights on land and in the oceans.

Scientific research into 3D digital applications in ecology has grown in the last decade. Landscape ...

2021-02-17

With every passing day, human technology becomes more refined and we become slightly better equipped to look deeper into biological processes and molecular and cellular structures, thereby gaining greater understanding of mechanisms underlying diseases such as cancer, Alzheimer's, and others.

Today, nanoimaging, one such cutting-edge technology, is widely used to structurally characterize subcellular components and cellular molecules such as cholesterol and fatty acids. But it is not without its limitations, as Professor Dae Won Moon of Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Technology (DGIST), Korea, lead scientist in a recent groundbreaking study advancing the field, explains: "Most advanced nanoimaging techniques use accelerated electron or ion beams ...

2021-02-17

Messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines to prevent COVID-19 have made headlines around the world recently, but scientists have also been working on mRNA vaccines to treat or prevent other diseases, including some forms of cancer. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Nano Letters have developed a hydrogel that, when injected into mice with melanoma, slowly released RNA nanovaccines that shrank tumors and kept them from metastasizing.

Cancer immunotherapy vaccines work similarly to mRNA vaccines for COVID-19, except they activate the immune system to attack tumors instead of a virus. These vaccines contain mRNA that encodes proteins made specifically by tumor cells. When the mRNA enters antigen-presenting cells, they begin making the tumor protein and displaying it on their surfaces, ...

2021-02-17

Swimming in indoor or outdoor pools is a healthy form of exercise and recreation for many people. However, studies have linked compounds that arise from chlorine disinfection of the pools to respiratory problems, including asthma, in avid swimmers. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Environmental Science & Technology have found that using a complementary form of disinfection, known as copper-silver ionization (CSI), can decrease disinfection byproducts and cell toxicity of chlorinated swimming pool water.

Disinfecting swimming pool water is necessary to inactivate harmful pathogens. Although an effective ...

2021-02-17

Washington, February 17, 2021--As higher education institutions worldwide transition to new methods of instruction, including the use of more pre-recorded videos, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, many observers are concerned that student learning is suffering as a result. However, a new comprehensive review of research offers some positive news for college students. The authors found that, in many cases, replacing teaching methods with pre-recorded videos leads to small improvements in learning and that supplementing existing content with videos results in strong learning benefits. The study ...

2021-02-17

Geologists have developed a new theory about the state of Earth billions of years ago after examining the very old rocks formed in the Earth's mantle below the continents.

Assistant Professor Emma Tomlinson from Trinity College Dublin and Queensland University of Technology's Professor Balz Kamber have just published their research in leading international journal, Nature Communications.

The seven continents on Earth today are each built around a stable interior called a craton, and geologists believe that craton stabilisation some 2.5 - 3 billion years ago was critical to the emergence of land masses on Earth.

Little is known about how cratons and their supporting ...

2021-02-17

A pioneering study of U.S nitrogen use in agriculture has identified 20 places across the country where farmers, government, and citizens should target nitrogen reduction efforts.

Nitrogen from fertilizer and manure is essential for crop growth, but in high levels can cause a host of problems, including coastal "dead zones", freshwater pollution, poor air quality, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions.

The 20 nitrogen "hotspots of opportunity" represent a whopping 63% of the total surplus nitrogen balance in U.S. croplands, but only 24% of U.S. cropland area. In total, ...

2021-02-17

Modern medical technology is helping scholars tell a more nuanced story about the fate of an ancient king whose violent death indirectly led to the reunification of Egypt in the 16th century BC. The research was published in Frontiers in Medicine.

Pharaoh Seqenenre-Taa-II, the Brave, briefly ruled over Southern Egypt during the country's occupation by the Hyksos, a foriegn dynasty that held power across the kingdom for about a century (c. 1650-1550 BCE). In his attempt to oust the Hyskos, Seqenenre-Taa-II was killed. Scholars have debated the exact nature of the pharaoh's death since his mummy was first discovered and studied in the 1880s.

These and subsequent examinations -- including an X-ray study in the 1960s -- noted the dead king had suffered several severe head injuries but no ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Body shape, beyond weight, drives fat stigma for women