How and when do children recognize power and social hierarchies?

This is the subject of a paper published on Feb.10 in PLOS ONE, by Jesús Bas and Núria Sebastián, members of the Center for Brain and Cognition

2021-02-17

(Press-News.org) Humans, like most social animals, tend to be organized hierarchically. In any group or social relationship there are always individuals who, for various reasons, significantly influence the behaviour of others. These individuals are attributed the highest status within the social group they belong to. As everyday examples of hierarchical relationships we find those of parents and children, teachers and students, bosses and workers, etc.

Given the pervasiveness of such social organization, in recent years studies have begun to ascertain how and when children begin to recognize which people have higher and which have lower social status. Specifically, the relationship was studied between social status and the "ability to control limited resources". This was the starting point for a study published on 10 February in the journal PLOS ONE by Jesús Bas and Núria Sebastián-Gallés, members of the Speech Acquisition and Perception research group (SAP) of the Center for Brain and Cognition (CBC), attached to the UPF Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC).

Studying power relations beyond physical strength

"Individuals that control resources are usually the ones that have a higher position within the group and vice versa. Different studies have shown that before the age of 15 months (Mascaro & Csibra, 2012), children understand that people who control one resource usually control others", explains Jesús Bas, first author of the study. Most of these studies were based mainly on the control of resources by means of physical strength. "Hence, at the Infant Research Laboratory (LRI) at UPF, we decided to study whether children are also able to identify individuals with a higher social status when physical strength does not come into the equation".

"So, we designed a study in which children aged 15-18 months repeatedly observed how two people wanted to grab a teddy bear at the same time. One of them (always the same) got it, thus displaying their "social power". Unlike in other studies, physical strength was not used, rather it looked like one of the agents yielded the teddy bear to the other, thus showing respect", say the authors of the article.

After, there was a change of scene and the two agents wanted to sit in the same chair. The children were presented with two different endings: the person who had got the teddy bear sat in the chair, or the person who had yielded it sat in the chair. When studying the children's reactions, we found that only the older children (18 months) were surprised when the person who had yielded the teddy bear sat in the chair. In other words, 18-month-olds , but not 15-month-olds, expected the same person who "controlled the teddy bears" to be the one who would have "control of the chair".

This study shows that before the age of two, children are able to infer social status without the need to witness how one individual dominates the other. In addition, the researchers found differences compared to previous studies. The fact that the younger infants (15 months) were not surprised by our study suggests that representing social status is more complex when it is not associated with physical force. The results demonstrate that children are able to understand complex social relationships beyond those established through primary mechanisms such as physical strength.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-17

Prolonged anesthesia, also known as medically induced coma, is a life-saving procedure carried out across the globe on millions of patients in intensive medical care units every year.

But following prolonged anesthesia--which takes the brain to a state of deep unconsciousness beyond short-term anesthesia for surgical procedures--it is common for family members to report that after hospital discharge their loved ones were not quite the same.

"It is long known that ICU survivors suffer lasting cognitive impairment, such as confusion and memory loss, that can languish for months and, in some cases, years," said Michael Wenzel, MD, lead author of a study published in PNAS this month that documents changes associated with prolonged anesthesia in the brains of mice.

Wenzel, a former ...

2021-02-17

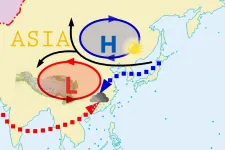

The Mongolian Cyclone is a major meteorological driving force across southeast Asia. This cyclone is known for transporting aerosols, affecting where precipitation develops. Meteorologists are seeking ways to improve seasonal prediction of the relationship between the Mongolian cyclone and South Asia high. These features are major components of the East Asian summer monsoon (EASM) and the corresponding heavy rain events. New research suggests that analyzing these phenomena in the upper-level atmosphere will enhance the summer rainfall forecast skill in China.

"The lower seasonal predictability of EASM may happen when the coupling wheel of Mongolian cyclone and South Asia high prevails over East Asia." said Prof. ...

2021-02-17

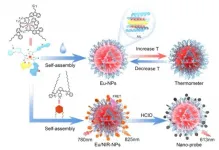

The unique properties of rare earth (RE) complexes including ligand-sensitized energy transfer, fingerprint-like emissions and long-lived emissions, make them promising materials for many applications, such as optical encoding, luminescence imaging/sensing and time-resolved luminescence detection. In particularly, the use of RE luminescent materials for in vitro and in vivo imaging can easily eliminate the autofluorescence of organisms and any interference from background fluorescence. However, most RE complexes have poor solubility and stability in aqueous solution and their luminescence can be easily quenched by nearby X-H (X ...

2021-02-17

A large-scale study of the link between innovation and financial performance in Australian companies has found more innovative companies post higher future profits and stock returns.

The findings highlight the significant financial benefits of innovation for companies, which in turn supports job creation and economic growth.

The study, conducted by Dr Anna Bedford, Dr Le Ma, Dr Nelson Ma and Kristina Vojvoda from the University of Technology Sydney, examined patent registrations from 1296 ASX-listed companies between 1997 and 2018.

They matched patent data with ...

2021-02-17

After more than 1,000 orthopaedic procedures at a city health system, roughly 61 percent of the opioids prescribed to patients went unused, according to new research. This was discovered within a study at the Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania that showed most patients responded to text messages designed to gauge patients' usage of their prescriptions. Knowing that so many patients are comfortable texting this information to their care teams is extremely useful as medical professionals look to right-size painkiller prescriptions and reduce the amount of opioids that might be misused when they're left over. This study was published in NEJM Catalyst.

"This approach is a step toward building a dynamic learning health system that evolves ...

2021-02-17

BOSTON -- Numerous studies have demonstrated the role of physical activity in improving heart health for patients with type 2 diabetes. But whether exercising at a certain time of the day promises an added health bonus for this population is still largely unknown. Now, research published in Diabetes Care by Brigham and Women's Hospital and Joslin Diabetes Center investigators, along with collaborators, reports a correlation between the timing of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and cardiovascular fitness and health risks for individuals who have type 2 diabetes and obesity or overweight.

The research team found that, in its study of ...

2021-02-17

A nasal antiviral created by researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons blocked transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in ferrets, suggesting the nasal spray also may prevent infection in people exposed to the new coronavirus, including recent variants

The compound in the spray--a lipopeptide developed by Matteo Porotto, PhD, and Anne Moscona, MD, professors in the Department of Pediatrics and directors of the Center for Host-Pathogen Interaction--is designed to prevent the new coronavirus from entering host cells.

The antiviral lipopeptide is inexpensive to produce, has a long shelf ...

2021-02-17

An engineered peptide given to ferrets two days before they were co-housed with SARS-CoV-2-infected animals prevented virus transmission to the treated ferrets, a new study shows. The peptides used are highly stable and thus have the potential to translate into effective intranasal prophylaxis to reduce infection and severe SARS-CoV-2 disease in humans, the study's authors say. The SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein binds to host cells to initiate infection. This stage in the virus life history is a target for drug inhibition. Here, researchers with past success designing lipopeptide fusion inhibitors that block this critical first step of infection for SARS-CoV-2 and other viruses sought to design ...

2021-02-17

Tsukuba, Japan -- As March comes around, many people experience hay fever. As excessive immune responses go, most would admit that hay fever really isn't that bad. At the other end of the spectrum are severely debilitating autoimmune diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis. A common thread in all these conditions are cytokines, molecules that cause inflammation. Recent research by the University of Tsukuba sheds light on the effect of excessive cytokines on neuronal and glial cells in the brain.

Researchers led by Professor Yosuke Takei and Assistant Professor Tetsuya Sasaki at the University of Tsukuba in ...

2021-02-17

Meteorologists frequently study precipitation events using radar imagery generated at both ground level and from satellite data. Radar sends out electromagnetic waves that "bounce" off ice or water droplets suspended in the air. These waves quickly return to the radar site in a process named "backscattering." Scientists have observed that backscattering reaches its peak during the melting process as water falls through the atmosphere. High backscattering typically results in warm color returns on a radar displays, indicating heavy precipitation.

However, recent case studies noted that partially frozen droplets seem ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How and when do children recognize power and social hierarchies?

This is the subject of a paper published on Feb.10 in PLOS ONE, by Jesús Bas and Núria Sebastián, members of the Center for Brain and Cognition