How the 'noise' in our brain influences our behavior

Neural variability provides an essential basis for how we perceive the world and react to it

2021-02-17

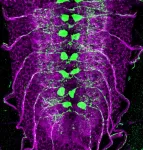

(Press-News.org) The brain's neural activity is irregular, changing from one moment to the next. To date, this apparent "noise" has been thought to be due to random natural variations or measurement error. However, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development have shown that this neural variability may provide a unique window into brain function. In a new Perspective article out now in the journal Neuron, the authors argue that researchers need to focus more on neural variability to fully understand how behavior emerges from the brain.

When neuroscientists investigate the brain, its activity seems to vary all the time. Sometimes activity is higher or lower, rhythmic or irregular. Whereas averaging brain activity has served as a standard way of visualizing how the brain "works," the irregular, seemingly random patterns in neural signals have often been disregarded. Strikingly, such irregularities in neural activity appear regardless of whether single neurons or entire brain regions are assessed. Brains simply always appear "noisy," prompting the question of what such moment-to-moment neural variability may reveal about brain function.

Across a host of studies over the past 10 years, researchers from the Lifespan Neural Dynamics Group (LNDG) at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Max Planck UCL Centre for Computational Psychiatry and Ageing Research have systematically examined the brain's "noise," showing that neural variability has a direct influence on behavior. In a new Perspective article published in the journal Neuron, the LNDG in collaboration with the University of Lübeck highlights what is now substantial evidence supporting the idea that neural variability represents a key, yet under-valued dimension for understanding brain-behavior relationships. "Animals and humans can indeed adapt successfully to environmental demands, but how can such behavioral success emerge in the face of neural variability? We argue that neuroscientists must grapple with the possibility that behavior may emerge because of neural variability, not in spite of it," says Leonhard Waschke, first author of the article and LNDG postdoctoral fellow.

A recent LNDG study published in the journal eLife exemplifies the direct link between neural variability and behavior. Participants' brain activity was measured via electroencephalography (EEG) while they responded to faint visual targets. When people were told to detect as many visual targets as possible, neural variability generally increased, whereas it was downregulated when participants were asked to avoid mistakes. Crucially, those who were better able to adapt their neural variability to these task demands performed better on the task. "The better a brain can regulate its 'noise,' the better it can process unknown information and react to it. Traditional ways of analyzing brain activity simply disregard this entire phenomenon." says LNDG postdoctoral fellow Niels Kloosterman, first author of this study and co-author of the article in Neuron.

The LNDG continues to demonstrate the importance of neural variability for successful human behavior in an ongoing series of studies. Whether one is asked to process a face, remember an object, or solve a complex task, the ability to modulate moment-to-moment variability seems to be required for optimal cognitive performance. "Neuroscientists have seen this 'noise' in the brain for decades but haven't understood what it means. A growing body of work by our group and others highlights that neural variability may indeed serve as an indispensable signal of behavioral success in its own right. With the increasing availability of tools and approaches to measure neural variability, we are excited that such a hypothesis is now immediately testable," says Douglas Garrett, Senior Research Scientist and LNDG group leader. In the next phases of their research, the group plans to examine whether neural variability and behavior can be optimized through brain stimulation, behavioral training, or medication.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-17

The researchers analysed how Spanish children and adolescents get to school, based on studies examining the commuting patterns of 36,781 individuals over a 7-year period (2010-2017)

Researchers from the University of Granada (UGR) have conducted the most comprehensive study to date on how Spanish children and young people get to school each day, to determine the active commuting rate.

The results showed that, between 2010 and 2017, in the region of 60% of Spanish children and adolescents actively commuted to school, with no significant variations being observed during this period.

The study, which was recently ...

2021-02-17

Our brains are complicated webs of billions of neurons, constantly transmitting information across synapses, and this communication underlies our every thought and movement.

But what happens to the circuit when a neuron dies? Can other neurons around it pick up the slack to maintain the same level of function?

Indeed they can, but not all neurons have this capacity, according to new research from the University of Chicago. By studying several neuron pairs that innervate distinct muscles in a fruit fly model, researchers found that some neurons compensate for ...

2021-02-17

Scientists have used cutting-edge research in quantum computation and quantum technology to pioneer a radical new approach to determining how our Universe works at its most fundamental level.

An international team of experts, led by the University of Nottingham, have demonstrated that only quantum and not classical gravity could be used to create a certain informatic ingredient that is needed for quantum computation. Their research "Non-Gaussianity as a signature of a quantum theory of gravity" has been published today in PRX Quantum.

Dr Richard Howl led the research during his time at the University of Nottingham's School of Mathematics, he said: "For ...

2021-02-17

One early feature of reporting on the coronavirus pandemic was the perception that sub-Saharan Africa was largely being spared the skyrocketing infection and death rates that were disrupting nations around the world.

While still seemingly mild, the true toll of the novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, on the countries of sub-Saharan Africa may be obscured by a tremendous variability in risk factors combined with surveillance challenges, according to a study published in the journal Nature Medicine by an international team led by Princeton University researchers and supported by Princeton's High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI).

"Although ...

2021-02-17

Adequate spacing between births can help to alleviate the likelihood of stunting in children, according to a new study from the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI).

In an article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, TCI postdoctoral associate Sunaina Dhingra and Director Prabhu Pingali find that differences in height between firstborn and later-born children may be due to inadequate time between births. When children are born at least three years after their older siblings, the height gap between them disappears.

India's family planning policies have focused on lowering population growth and postponing pregnancy to improve maternal health outcomes. But while the overall fertility rate has fallen as low ...

2021-02-17

WASHINGTON -- Researchers have developed an extremely sensitive miniaturized optical fiber sensor that could one day be used to measure small pressure changes in the body.

"Our new pressure sensor was designed for medical applications and overcomes many of the issues of using silica-based fibers," said research team leader Hwa-Yaw Tam from The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. "It is sensitive enough to measure pressure inside lungs while breathing, which changes by just a few kilopascals."

The researchers describe their new optical fiber sensor in The ...

2021-02-17

A new X-ray imaging scanner to help surgeons performing breast tumour removal surgery has been developed by UCL experts.

Most breast cancer operations are what are known as conserving surgeries, which remove the cancerous tumour rather than the whole breast. Second operations are often required if the margins (edges) of the extracted tissue are found to not be clear of cancer.

Researchers at UCL, Queen Mary University of London, Barts Health NHS Trust and Nikon used a new approach to x-ray imaging which allows surgeons to assess extracted tissue intraoperatively, or during the initial surgery, giving 2.5 times better detection of diseased tissue in the margins than with standard ...

2021-02-17

Polyisobutenyl succinic anhydrides (PIBSAs) are important for the auto industry because of their wide use in lubricant and fuel formulations. Their synthesis, however, requires high temperatures and, therefore, higher cost.

Adding a Lewis acid--a substance that can accept a pair of electrons--as a catalyst makes the PIBSA formation more efficient. But which Lewis acid? Despite the importance of PIBSAs in the industrial space, an easy way to screen these catalysts and predict their performance hasn't yet been developed.

New research led by the Computer-Aided Nano and Energy Lab (CANELa) at the University of Pittsburgh Swanson School of Engineering, in collaboration with the ...

2021-02-17

Wearable sleep tracking devices - from Fitbit to Apple Watch to never-heard-of brands stashed away in the electronics clearance bin - have infiltrated the market at a rapid pace in recent years.

And like any consumer products, not all sleep trackers are created equal, according to West Virginia University neuroscientists.

Prompted by a lack of independent, third-party evaluations of these devices, a research team led by Joshua Hagen, director of the Human Performance Innovation Center at the WVU Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, tested the efficacy of eight commercial sleep trackers.

Fitbit and Oura came out on top in measuring total sleep time, total wake ...

2021-02-17

SAN ANTONIO -- Patients should be assessed for frailty before having many types of surgery, even if the surgery is considered low risk, a review of two national patient databases shows.

Frailty is a clinical syndrome marked by slow walking speed, weak grip, poor balance, exhaustion and low physical activity. It is an important risk factor for death after surgery, although the association between frailty and mortality across surgical specialties is not well understood.

The study, conducted by faculty at multiple institutions including The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UT Health San Antonio), mined patient data from the Veterans Affairs (VA) Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) National Surgical Quality ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How the 'noise' in our brain influences our behavior

Neural variability provides an essential basis for how we perceive the world and react to it