(Press-News.org) Almost 100 years ago, a revolutionary discovery was made in the field of physics: microscopic matter exhibits wave properties. Over the decades, more and more precise experiments have been used to measure the wave properties of electrons in particular. These experiments were mostly based on spectroscopic analysis of the hydrogen atom and they enabled verifying the accuracy of the quantum theory of the electron.

For heavy elementary particles - for example protons - and nuclides (atomic nuclei), it is difficult to measure their wave properties accurately. In principle, however, these properties can be seen everywhere. In molecules, the wave properties of atomic nuclei are obvious and can be observed in the internal vibrations of the atomic nuclei against each other. Such vibrations are enabled by the electrons in molecules, that create a bond between the nuclei that is 'soft' rather than rigid. For example, nuclear vibrations occur in every molecular gas under normal conditions, such as in air.

The wave properties of the nuclei are demonstrated by the fact that the vibration cannot have an arbitrary strength - i.e. energy - as would be the case with a pendulum for example. Instead, only precise, discrete values known as 'quantized' values are possible for the energy.

A quantum jump from the lowest vibrational energy state to a higher energy state can be achieved by radiating light onto the molecule, whose wavelength is precisely set so that it corresponds exactly to the energy difference between the two states.

To investigate the wave properties of nuclides very accurately, one needs both a very precise measuring method and a very precise knowledge of the binding forces in the specific molecule, because these determine the details of the wave motion of the nuclides. This then makes it possible to test fundamental laws of nature by comparing their specific statements for the nuclide investigated with the measurement results.

Unfortunately, it is not yet possible to make precise theoretical predictions regarding the binding forces of molecules in general - the quantum theory to be applied is mathematically too complex to handle. Consequently, it is not possible to investigate the wave properties in any given molecule accurately. This can only be achieved with particularly simple molecules.

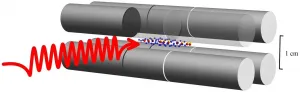

Together with its long-standing cooperation partner V. I. Korobov from the Bogoliubov Laboratory of Theoretical Physics at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia, Prof. Schiller's research team is dedicated to precisely one such molecule, namely the hydrogen molecular ion HD+. HD+ consists of a proton (p) and the nuclide deuteron (d). The two are linked together by a single electron. The relative simplicity of this molecule means that extremely accurate theoretical calculations can now be performed. It was V.I. Korobov who achieved this, after refining his calculations continuously for over twenty years.

For charged molecules such as the hydrogen molecule, an accessible yet highly precise measuring technique did not exist until recently. Last year, however, the team led by Prof. Schiller developed a novel spectroscopy technique for investigating the rotation of molecular ions. The radiation used then is referred to as 'terahertz radiation', with a wavelength of about 0.2 mm.

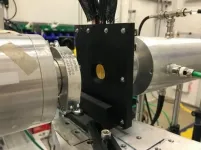

The team has now been able to show that the same approach also works for excitation of molecular vibrations using radiation with a wavelength that is 50 times shorter. To do this, they had to develop a particularly frequency-sharp laser that is one of a kind worldwide.

They demonstrated that this extended spectroscopy technique has a resolution capacity for the radiation wavelength for vibrational excitation that is 10,000 times higher than in previous techniques used for molecular ions. Systematic disturbances of the vibrational states of the molecular ions, for example through interfering electrical and magnetic fields, could also be suppressed by a factor of 400.

Ultimately, it emerged that the prediction of quantum theory regarding the behaviour of the atomic nuclei proton and deuteron was consistent with the experiment with a relative inaccuracy of less than 3 parts in 100 billion parts.

If it is assumed that V.I. Korobov's prediction based on quantum theory is complete, the result of the experiment can also be interpreted differently - namely as the determination of the ratio of electron mass to proton mass. The value derived corresponds very well with the values determined by experiments by other working groups using completely different measuring techniques.

Prof. Schiller emphasises: "We were surprised at how well the experiment worked. And we believe that the technology we developed is applicable not only to our 'special' molecule but also in a much wider context. It will be exciting to see how quickly the technology is adopted by other working groups."

INFORMATION:

Original publication

I. V. Kortunov, S. Alighanbari, M. G. Hansen, G. S. Giri, V. I. Korobov & S. Schiller, Proton-electron mass ratio by high-resolution optical spectroscopy of ion ensembles in the resolved-carrier regime, Nature Physics 2021

DOI: 10.1038/s41567-020-01150-7

An international team of researchers has developed a framework for assessing brand reputation in real time and over time, and built a tool for implementing the framework. In a proof of concept demonstration looking at leading brands, the researchers found that changes in a given brand's stock shares reflected real-time changes in the brand's reputation.

"We've developed something we call the Brand Reputation Tracker that mines social media text on Twitter and uses 11 different measures to give us an in-depth understanding of how users feel about individual brands," says Bill Rand, co-lead author of the paper and an associate professor of marketing in North Carolina State University's Poole College of Management.

The Brand Reputation Tracker ...

Evidence that a sense of our physical selves can develop even without the sense of touch has been uncovered in a new study by researchers in the UK and the United States.

The research shows that if someone loses their sense of touch and 'proprioception' - their sense of body position - as an adult, they may learn compensatory skills using visual cues and conscious thought, or reasoning, to move their bodies.

Someone who has never had a sense of touch or proprioception, however, can find faster, unconscious ways of processing visual cues to move and orient themselves.

A team at the University of Birmingham collaborated with researchers at Bournemouth University and the University of Chicago on the study, ...

In the late 1980s and 1990s, researchers at ETH Zurich discovered the first indications that the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface had been steadily declining since the 1950s. The phenomenon was known as "global dimming". However, a reversal in this trend became discernible in the late 1980s. The atmosphere brightened again at many locations and surface solar radiation increased.

"In previous studies, we showed that the amount of sunlight that reaches the Earth's surface is not constant over many decades but instead varies substantially - a phenomenon known as global dimming and brightening," ...

Researchers from Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, the state's only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center, evaluated the frequency of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, on various environmental surfaces in outpatient and inpatient hematology/oncology settings located within Rutgers Cancer Institute and Robert Wood Johnson University Hospital, an RWJBarnabas Health facility. The study revealed extremely low detection of SARS-CoV-2 on environmental surfaces across multiple outpatient and inpatient oncology areas, including an active COVID-19 floor. Andrew M. Evens, DO, MSc, FACP, associate director for clinical services and director of the Lymphoma Program at Rutgers Cancer Institute and medical director of the oncology service ...

Annapolis, MD; February 17, 2021--When the invasive spotted lanternfly arrived in the United States in 2014, it was immediately recognized for the threat it posed to native plants and crops. A community of researchers and experts in science, agriculture, and government sprang into action to respond, improving our chances for containing the pest and curbing its potential for damage.

While the effort continues, a new collection curated by the Entomological Society of America's family of journals showcases the growing body of research that is helping us understand the spotted lanternfly's biology and how to contain it. The collection features 25 articles published ...

When there is a choice, wolves in Mongolia prefer to feed on wild animals rather than grazing livestock. This is the discovery by a research team from the University of Göttingen and the Senckenberg Museum Görlitz. Previous studies had shown that the diet of wolves in inland Central Asia consists mainly of grazing livestock, which could lead to increasing conflict between nomadic livestock herders and wild predatory animals like wolves. The study has been published in the journal Mammalian Biology.

Around three million people live in Mongolia, making it the most sparsely populated country in the world. In addition, there are more than 40 million grazing animals. These animals are not just a source of food but also the ...

By 2030 only EV's will be in production, meaning manufacturers are racing to create a high-energy battery that's affordable and charges efficiently, but conventional battery cathodes cannot reach the targets of 500Wh/Kg

Lithium-excess cathodes offer the ability to reach 500Wh/Kg but unlocking their full capacity means understanding how they can store charge at high voltages.

A new X-ray study lead by WMG, University of Warwick has resolved how the metals and oxygen facilitate the charge storage at high voltages.

High energy storage batteries for EVs need high capacity battery cathodes. New lithium-excess magnesium-rich cathodes are expected to replace existing nickel-rich cathodes but understanding how the magnesium and oxygen accommodate charge storage at high ...

As investors set their sights on the mineral resources of the deep seabed, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) is developing regulations that will govern their future exploration and possible exploitation. A new IASS Policy Brief, published in cooperation with the Federal Environment Agency (UBA), presents three recommendations to ensure that future deep seabed mining would be to the common benefit all humankind, as required by international law.

The ecosystems of the deep ocean are complex and provide a wide range of benefits to humankind. Oceans soak up carbon dioxide and act as a natural buffer to global warming in addition to regulating the climate and serving as an important ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Researchers report that 4-6-year-old children who walk further than their peers during a timed test - a method used to estimate cardiorespiratory health - also do better on cognitive tests and other measures of brain function. Published in the Journal of Clinical Medicine, the study suggests that the link between cardiorespiratory fitness and cognitive health is evident even earlier in life than previously appreciated.

Most studies of the link between fitness and brain health focus on adults or preadolescent or adolescent children, said doctoral student Shelby Keye, who led the new research with Naiman Khan, a professor of kinesiology and ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Workers with science, technology, engineering and math backgrounds are typically in high demand - but the demand isn't so overwhelming that a "skills gap" exists in the labor market for information technology help desk workers, one of the largest computer occupations in the U.S., says new research from a University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign expert who studies labor economics and work issues.

The incidence of prolonged hiring difficulties for STEM workers is modest, with only 11%-15% of IT help desks in the U.S. showing vacancy patterns that might be consistent with persistent hiring frictions, said Andrew Weaver, a professor ...