Sweet marine particles resist hungry bacteria

All algae sugars are entirely degraded by bacteria; well, not all; one sugar holds out against the invaders and could act as an important carbon sink

2021-02-19

(Press-News.org) A major pathway for carbon sequestration in the ocean is the growth, aggregation and sinking of phytoplankton - unicellular microalgae like diatoms. Just like plants on land, phytoplankton sequester carbon from atmospheric carbon dioxide. When algae cells aggregate, they sink and take the sequestered carbon with them to the ocean floor. This so called biological carbon pump accounts for about 70 per cent of the annual global carbon export to the deep ocean. Estimated 25 to 40 per cent of carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning emitted by humans may have been transported by this process from the atmosphere to depths below 1000 meter, where carbon can be stored for millennia.

Fast bacterial community

Yet, even it is very important, it is still poorly understood how the carbon pump process works at the molecular level. Scientists of the research group Marine Glycobiology, which is located at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology and the MARUM - Center for Marine Environmental Sciences at the University of Bremen, investigate in this context marine polysaccharides - meaning compounds made of multiple sugar units - which are produced by microalgae. These marine sugars are very different on a structural level and belong to the most complex biomolecules found in nature. One single bacterium is not capable to process this complex sugar-mix. Therefore a whole bunch of metabolic pathways and enzymes is needed. In nature, this is achieved by a community of different bacteria that work closely and very efficiently together - a perfect coordinated team. This bacterial community works so well that the major part of microalgal sugars are degraded before they aggregate and start to sink. A large amount of the sequestered carbon therefore is released back into the atmosphere.

But, how is it possible that nevertheless a lot of carbon is still transported to the deep-sea? The scientists of the group Marine Glycobiology now revealed a component that may be involved in this process and published their results in the journal Nature Communications. "We found a microalgal fucose-containing sulphated polysaccharide, in short FCSP, that is resistant to microbial degradation," says Silvia Vidal-Melgosa, first author of the paper. "This discovery challenges the existing paradigm that polysaccharides are rapidly degraded by bacteria." This assumption is the reason why sugars are overlooked as a carbon sink - until now. Analyses of the bacterial community, which were performed by scientists from the department of Molecular Ecology at the MPI in Bremen and the University of Greifswald, showed bacteria had a low abundance of enzymes for the degradation of this sugar.

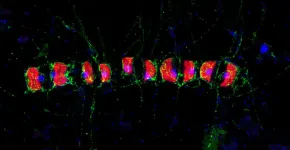

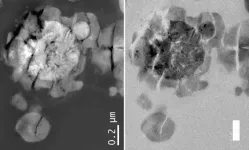

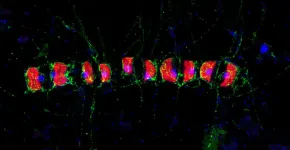

A crucial part of the finding is that this microbial resistant sugar formed particles. During growth and upon death unicellular diatoms release a large amount of unknown, sticky long-chained sugars. With increasing concentration, these sugar chains stick together and form molecular networks. Other components attach to these small sugar flakes, such as other sugar pieces, diatom cells or minerals. This makes the aggregates larger and heavier and thus they sink faster than single diatom cells. These particles need about ten days to reach a depth of 1000 meters - often much longer. This means that the sticky sugar core has to resist biodegradation for at least so long to hold the particle together. But this is very difficult as the sugar-eating bacteria are very active and always hungry.

New method to analyse marine sugars

In order to unravel the structures of microalgae polysaccharides and identify resistant sticky sugars, the scientists of the research group Marine Glycobiology are testing new methods. This is necessary because marine sugars are found within complex organic matter mixtures. In the case of this study, they used a method which originates from medical and plant research. It combines the high-throughput capacity of microarrays with the specificity of monoclonal antibody probes. This means, that the scientists extracted the sugar-molecules out of the seawater samples and inserted them into a machine that works like a printer, which doesn't use ink but molecules. The molecules are separately "printed" onto nitrocellulose paper, in form of a microarray. A microarray is like a microchip, small like a fingernail, but can contain hundreds of samples. Once the extracted molecules are printed onto the array it is possible to analyse the sugars present on them. This is achieved by using the monoclonal antibody probes. Single antibodies are added to the arrays and as they react only with one specific sugar the scientists can see, which sugars are present in the samples.

"The novel application of this technology enabled us to simultaneously monitor the fate of multiple complex sugar molecules during an algal bloom," says Silvia Vidal-Melgosa. "It allowed us to find the accumulation of the sugar FCSP, while many other detected polysaccharides were degraded and did not store carbon." This study proves the new application of this method. "Notably, complex carbohydrates have not been measured in the environment before at this high molecular resolution," says Jan-Hendrik Hehemann, leader of the group Marine Glycobiology and senior author of the study. "Consequently, this is the first environmental glycomics dataset and therefore the reference for future studies about microbial carbohydrate degradation".

Next step: Search for particles in the deep sea

The discovery of FCSP in diatoms, with demonstrated stability and adhesive properties, provides a previously uncharacterised polysaccharide that contributes to particle formation and potentially therefore to carbon sequestration in the ocean. One of the next steps in the research is "to find out, if the particles of this sugar exist in the deep ocean," says Hehemann. "That would indicate that the sugar is stable and constitutes an important player of the biological carbon pump." Furthermore, the observed stability against bacterial degradation, and the structure and physicochemical behaviour of diatom FCSP point towards specific biological functions. "Given its stability against degradation, FCSP, which coats the diatom cells, may function as a barrier protecting the cell wall against microbes and their digestive enzymes," says Hehemann. And last but not least, another open question to be solved: These sugar particles were found in the North Sea near the island of Helgoland. Do they also exist in the sea of other regions in the world?

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-19

Early Mars is considered as an environment where life could possibly have existed. There was a time in the geological history of Mars when it could have been very similar to Earth and harbored life as we know it. In opposite to the current Mars conditions, bodies of liquid water, warmer temperature, and higher atmospheric pressure could have existed in Mars' early history. Potential early forms of life on Mars should have been able to use accessible inventories of the red planet: derive energy from inorganic mineral sources and transform CO2 into biomass. Such living entities are rock-eating microorganisms, called "chemolithotrophs", which ...

2021-02-19

The ability to speak is one of the essential characteristics that distinguishes humans from other animals. Many people would probably intuitively equate speech and language. However, cognitive science research on sign languages since the 1960s paints a different picture: Today it is clear, sign languages are fully autonomous languages and have a complex organization on several linguistic levels such as grammar and meaning. Previous studies on the processing of sign language in the human brain had already found some similarities and also differences between sign ...

2021-02-19

The last complete reversal of the Earth's magnetic field, the so-called Laschamps event, took place 42,000 years ago. Radiocarbon analyses of the remains of kauri trees from New Zealand now make it possible for the first time to precisely time and analyse this event and its associated effects, as well as to calibrate geological archives such as sediment and ice cores from this period. Simulations based on this show that the strong reduction of the magnetic field had considerable effects in the Earth's atmosphere. This is shown by an international team led by Chris Turney from the Australian University of New South Wales, with the participation of Norbert Nowaczyk from the German Research Centre for ...

2021-02-19

Researchers at Tampere University have successfully used artificial intelligence to predict nonlinear dynamics that take place when ultrashort light pulses interact with matter. This novel solution can be used for efficient and fast numerical modelling, for example, in imaging, manufacturing and surgery. The findings were published in the prestigious Nature Machine Intelligence journal.

Artificial intelligence can distinguish different types of laser pulse propagation, just as it recognizes subtle differences of expression in facial recognition. The newly found solution can make it simpler to design experiments in fundamental research and will allow algorithms ...

2021-02-19

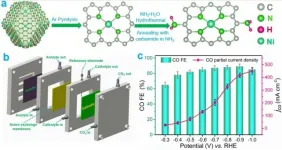

Carbon dioxide (CO2) electrocatalytic reduction driven by renewable electricity can solve the problem of excessive CO2 emissions. Since CO2 is thermodynamically stable, efficient catalysts are needed to reduce the energy consumption in the process.

The single-atom catalysts immobilized on nitrogen-doped carbon supports (M-N/C) have been widely used for CO2 electrocatalytic reduction reaction due to their high atom utilization efficiency.

Recently, a research team led by Prof. LIU Licheng from the Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology (QIBEBT) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) proposed a two-step amination strategy to regulate the electronic structure of M-N/C catalysts (M=Ni, Fe, Zn) and enhance the intrinsic activity of CO2 electrocatalytic reduction.

In ...

2021-02-19

EUGENE, Ore. -- Feb. 19, 2021 -- Friction caused by dry Martian dust particles making contact with each other may produce electrical discharge at the surface and in the planet's atmosphere, according University of Oregon researchers.

However, such sparks are likely to be small and pose little danger to future robotic or human missions to the red planet, they report in a paper published online and scheduled to appear in the March 15 print issue of the journal Icarus.

Viking landers in the 1970s and orbiters since then detected silts, clays, wind-blown bedforms and dust devils on Mars, raising questions about potential electrical activity.

Scientists ...

2021-02-19

China is just one of many countries in the Northern Hemisphere having what researchers are calling an "extremely cold winter," due in part to both the tropical Pacific and the Arctic, according to an analysis of temperatures from Dec. 1, 2020, to mid-January of 2021. A country-specific case study, the investigation potentially has far-reaching implications for predictions and early warnings to protect against harmful impacts, researchers said.

The results were published online, ahead of print, on Feb. 12 in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

"We are trying to explain why the countries in the Northern Hemisphere ...

2021-02-19

Nanoparticles used in drug delivery systems, bioimaging, and regenerative medicine migrate from tissues to lymphatic vessels after entering the body, so it is necessary to clarify the interaction between nanoparticles and lymphatic vessels. Although technology to observe the flow of nanoparticles through lymphatic vessels in vivo has been developed, there has been no method to evaluate the flow of nanoparticles in a more detailed and quantitative manner ex vivo. Thus, research was conducted to develop an ex vivo lymphatic vessel lumen perfusion system to determine how nanoparticles move in lymphatic vessels and how they affect the physiological movement of lymphatic vessels.

Nanoparticles introduced into the ...

2021-02-19

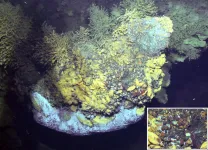

A research team led by Prof. QIAN Peiyuan, Head and Chair Professor from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST)'s Department of Ocean Science and David von Hansemann Professor of Science, has published their cutting-edge findings of symbiotic mechanisms of a deep-sea vent snail (Gigantopelta aegis) in the scientific journal Nature Communications. They discovered that Gigantopelta snail houses both sulfur-oxidizing bacteria and methane-oxidizing bacteria inside its esophageal gland cells (part of digestive system) as endosymbionts. By decoding the ...

2021-02-19

A new study looking at how COVID-19 affects people with asthma provides reassurance that having the condition doesn't increase the risk of severe illness or death from the virus.

George Institute for Global Health researchers in Australia analysed data from 57 studies with an overall sample size of 587,280. Almost 350,000 people in the pool had been infected with COVID-19 from Asia, Europe, and North and South America and found they had similar proportions of asthma to the general population.

The results, published in the peer-reviewed END ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Sweet marine particles resist hungry bacteria

All algae sugars are entirely degraded by bacteria; well, not all; one sugar holds out against the invaders and could act as an important carbon sink