CUHK physicists discover new route to active matter self-organisation

Provides new directions on fabricating self-driven devices and microbial physiology

2021-02-22

(Press-News.org) This new finding may pave the way for fabricating a new class of self-driven devices and materials, such as the ability to control the rhythmic movement of soft robots without relying on electronic circuits, and for the study of microbial physiology. It has been published in the scientific journal Nature.

A fast growing and interdisciplinary field, active matter science studies systems consist of units where energy is spent locally to generate mechanical work. Active matter includes all living organisms from cells to animals, biopolymers driven by molecular motors, and synthetic self-propelled materials. Self-organisation (the process of producing ordered structures via interaction between individual units) principles learned from these systems may find applications in tissue engineering and in fabricating new bio-inspired devices or materials.

The study was conceived by Professor Wu and his former PhD student Song Liu (currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Basic Science in Korea). They have a long term interest in understanding the physic phenomena of self-organisation in biological active matter, with a focus on active fluids consisting of motile microorganisms. In a previous paper co-worked with overseas physicists published in Nature in 2017, they reported a weak synchronization mechanism for biological collective oscillation, in which robust temporal order emerges from a large number of erratic but weakly coupled trajectories of individual cells in bacterial suspensions. However, the simultaneous control of spatial and temporal order is more challenging.

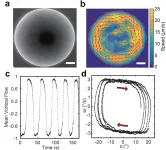

In the new study, the CUHK research team found clues in viscoelasticity, a common property of complex fluids which have both fluid-like and solid-like responses under deformation. While manipulating the viscoelasticity of a bacterial active fluid with DNA polymers, the team found spectacular phenomena. The bacterial active fluid first self-organises in space into a millimeter-scale rotating vortex, then displays temporal organisation as the giant vortex switches its global chirality periodically with tunable frequency, like a self-driven torsional pendulum. The team believed that these striking phenomena may possibly arise from the interplay between active forcing and viscoelastic stress relaxation. Viscoelastic relaxation occurs on a time scale corresponding to the transition from solid-like to fluid-like responses when a complex fluid is deformed.

To further understand the observed phenomena, the CUHK researchers teamed up with theoretical physicists Cristina Marchetti, Professor of the University of California, Santa Barbara and her former PhD student Suraj Shankar, now a Junior Fellow of Harvard University. The two theorists developed an active matter model that couples bacterial activity, polymer elastic stress, and the fields of bacterial velocity and polarisation. Analysis and computer simulations of the model reproduce all the major experimental findings, and also explain the onset of spatial and temporal order in terms of the competition between the time scales of viscoelastic relaxation and active forcing.

These new findings demonstrate experimentally for the first time that viscoelasticity of materials can be harnessed to control active matter's self-organisation. It will fuel the development of non-equilibrium physics and may pave the way for fabricating a new class of adaptive self-driven devices and materials. For instance, when coupled to actuation systems of soft robots, the millimeter-scale tunable and self-oscillating vortex may be used as a "clock generator" which provides timing signals for programmed microfluidic pumping and for controlling the rhythmic movement of soft robots, without relying on electronic circuits. Moreover, bacteria in biofilms and animal gastrointestinal tracts often swim in viscoelastic fluids abundant in long-chain polymers. The new findings also suggest that the viscoelasticity of the environment may modify the collective motion patterns of bacteria, thereby influencing the dispersal of biofilms and the translocation of gut microbiome.

INFORMATION:

The CUHK research team involved in the study was supported by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, and the CUHK Research Committee. The full text of the research paper can be found: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-03168-6.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-22

A SARS-CoV-2 tracker uses publicly available sequencing data to show how the virus is changing and spreading over time. The tracker, called CovMT, was developed at KAUST and is expected to help researchers and policymakers understand the evolution of the virus's mutations. This could have implications for vaccine development, patient treatment and the implementation of restrictions.

"As new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus emerge, authorities around the world need to know if these, or similar variants, have entered their countries," says computational biologist, Intikhab Alam, who designed ...

2021-02-22

Treating waste brine using a self-cleaning crystallizer that runs on solar power could be an eco-friendly and efficient way to make seawater desalination more sustainable.

In desert regions, seawater desalination provides essential freshwater for drinking and agriculture. A major problem is that the process generates vast quantities of concentrated brine that is often released into nearby lakes and rivers or back into the sea, harming vegetation and marine life. "With tightening environmental regulations and increasing public awareness, there is pressure to treat brine with zero liquid discharge," says Chenlin Zhang, a Ph.D. student in KAUST. This means extracting every last drop of water while leaving behind solid mineral crystals that can be salvaged for other uses.

Crystallization ...

2021-02-22

Monoclonal antibodies are part of the therapeutic arsenal for eliminating cancer cells. Some make use of the immune system to act and belong to a class of treatment called "immunotherapies." But how do these antibodies function within the tumor? And how can we hope to improve their efficacy? Using innovative in vivo imaging approaches, scientists from the Institut Pasteur and Inserm visualized in real time how anti-CD20 antibodies, used to treat B-cell lymphoma, guide the immune system to attack tumor cells. Their findings were published in the journal Science Advances on February 19, 2021

Anti-CD20 antibodies are used in clinical practice to treat patients with B-cell lymphoma, a type of blood cancer. The treatment, often used in combination with chemotherapy, has been ...

2021-02-22

A mixture of smaller countries led by New Zealand, Vietnam, Taiwan, Thailand, Cyprus, Rwanda and Iceland led the world 's Top 10 countries to manage their COVID-19 response well, according to a new study.

In the study, published in The BMJ, lead researcher Flinders University's Professor Fran Baum joined experts from around the world to reflect upon the Global Health Security Index (October 2019) predictions for a public health emergency.

Along with Australia, Latvia and Sri Lanka among the best responders, the list highlights some of the 10 key causes of why some countries were successful or not in containing COVID-19 pandemic over the past year.

The US, UK, Netherlands, Australia, Canada, Thailand, Sweden, Denmark, South Korea, Finland (France, Slovenia and Switzerland) ...

2021-02-22

People with periodontitis are at higher risk of experiencing major cardiovascular events, according to new research from Forsyth Institute and Harvard University scientists and colleagues.

In a longitudinal study published recently in the Journal of Periodontology, Dr. Thomas

Van Dyke, Senior Member of Staff at Forsyth, Dr. Ahmed Tawakol of Massachusetts General Hospital, and their collaborators showed that inflammation associated with active gum disease was predictive of arterial inflammation, which can cause heart attacks, strokes, and other dangerous manifestations of cardiovascular disease.

For ...

2021-02-22

Despite deaths and hospitalisations linked to many new psychoactive substances (NPS), an international wastewater study led by the University of South Australia shows just how prevalent 'party pills' and 'bath salts' are in different parts of the world.

In a new paper published in Water Research, the world's most comprehensive wastewater analysis of NPS shows the pattern of designer drug use in the 2019/2020 New Year in 14 sites across Australia, New Zealand, China, The Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Norway and the United States.

UniSA analytical chemist Dr Richard Bade says samples were collected over the New Year in each country and ...

2021-02-22

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Oregon State University and U.S. Department of Agriculture researchers have significantly expanded the understanding of the hop genome, a development with important implications for the brewing industry and scientists who study the potential medical benefits of hops.

"This research has the unique ability to impact several different fields," said David Hendrix, an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics and the School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Oregon State. "If you're talking to beer drinkers, they will be excited about the brewing side. If you are talking to the medical field, they are going to be excited about the pharmaceutical potential."

The findings are outlined in ...

2021-02-22

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Scientists at Oregon State University and the U.S. Forest Service have demonstrated that DNA extracted from water samples from rivers across Oregon and Northern California can be used to estimate genetic diversity of Pacific salmon and trout.

The findings, just published in the journal Molecular Ecology, have important implications for conservation and management of these species, which are threatened by human activities, including those exacerbating climate change.

"There has been a dearth of this kind of data across the Northwest," said Kevin Weitemier, a postdoctoral fellow at Oregon State and lead author of the paper. "This allows us to get a quick snapshot of multiple populations and species all at once."

In addition to demonstrating ...

2021-02-22

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Desert bighorn sheep in the Mojave National Preserve in California and surrounding areas appear to be more resilient than previously thought to a respiratory disease that killed dozens of them and sickened many more in 2013, a new study has found.

Clint Epps, a wildlife biologist at Oregon State University, and several co-authors, found that exposure to one of the bacteria associated with the disease is more widespread among bighorn sheep populations in the Mojave, and that its presence dates further back, than scientists thought. But they also found that the overall number of infected bighorn has declined since 2013 in the populations surveyed.

Epps and his colleagues, including Nicholas Shirkey, an environmental scientist with ...

2021-02-22

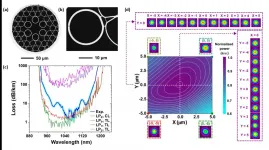

Recent spotlights on IC-HCPCFs are due to the recently demonstrated outstanding ultralow-loss performances and their application capabilities. Nevertheless, while their attenuation achieves impressive figures, the challenge of accomplishing a low loss, single-mode (SM), and polarization-maintaining HCPCF perseveres.

In a new paper published in Light: Science & Applications, a team of scientists, led by Professor Fetah Benabid from the University of Limoges, France, and in collaboration of the University of Modena, Italy and the company GLOphotonics, proposed and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] CUHK physicists discover new route to active matter self-organisation

Provides new directions on fabricating self-driven devices and microbial physiology