INFORMATION:

Politics and the brain: Attention perks up when politicians break with party lines

fMRI study shows stronger neurological responses for politically incongruent positions

2021-02-22

(Press-News.org) In a time of extreme political polarization, hearing that a political candidate has taken a stance inconsistent with their party might raise some questions for their constituents.

Why don't they agree with the party's position? Do we know for sure this is where they stand?

New research led by University of Nebraska-Lincoln political psychologist Ingrid Haas has shown the human brain is processing politically incongruent statements differently -- attention is perking up -- and that the candidate's conviction toward the stated position is also playing a role.

In other words, there is a stronger neurological response happening when, for example, a Republican takes a position favorable to new taxes, or a Democratic candidate adopts an opinion critical of environmental regulation, but it may be easier for us to ignore these positions when we're not exactly sure where the candidate stands.

Using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, or fMRI, at Nebraska's Center for Brain Biology and Behavior, Haas and her collaborators, Melissa Baker of the University of California-Merced, and Frank Gonzalez of the University of Arizona, examined the insula and anterior cingular cortex in 58 individuals -- both regions of the brain that are involved with cognitive function -- and found increased activity when the participants read statements incongruent with the candidate's stated party affiliation. The participants were also shown a slide stating how certain the candidates felt about the positions.

"The biggest takeaway is that people paid more attention to uncertainty when it was attached to the consistent information, and they were more likely to dismiss it when it was attached to the inconsistent information," Haas, associate professor of political science, said. "In these brain regions, the most activation was to incongruent trials that were certain.

"If you definitely know that the candidate is deviating from party lines, so to speak, that seemed to garner more response from our participants, whereas if there's a suspicion that they're deviating from party line, but it's attached to more uncertainty, we didn't see participants engaged in so much processing of that information."

Haas said these trials didn't examine what the voter might decide to do with this information, but that participants were paying more attention to incongruent statements overall.

"We didn't look at whether they're less likely to vote for the candidate, but what we show is increased neural activation associated with those trials," Haas said. "They are taking longer to process the information and taking longer to make a decision about how they feel about it. That does seem to indicate that it's garnering more attention."

The research raises a possible answer to the perennial question of why politicians are frequently less explicit in their opinions, or why they may flip-flop on a stated position.

"Our work points to a reason why politicians might deploy uncertainty in a strategic way," Haas said. "If a politician has a position that is definitely incongruent from the party's stated position, the idea is that rather than put that out there, given that people might grasp onto it and pay more attention to it, it might be strategic for them to mask their true positions instead."

The article, "Political uncertainty moderates neural evaluation of incongruent policy positions," was published Feb. 22 in a special issue of Philosophical Transactions B, "The political brain: neurocognitive and computational mechanisms."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

NYU Abu Dhabi researcher sheds new light on the psychology of radicalization

2021-02-22

Abu Dhabi, UAE, February 22, 2021: Learning more about what motivates people to join violent ideological groups and engage in acts of cruelty against others is of great social and societal importance. New research from Assistant Professor of Psychology at NYUAD Jocelyn Bélanger explores the idea of ideological obsession as a form of addictive behavior that is central to understanding why people ultimately engage in ideological violence, and how best to help them break this addiction.

In the new study, END ...

Toddler sleep patterns matter

2021-02-22

Establishing a consistent sleep schedule for a toddler can be one of the most challenging aspects of child rearing, but it also may be one of the most important.

Research findings from a team including Lauren Covington, an assistant professor in the University of Delaware School of Nursing, suggest that children with inconsistent sleep schedules have higher body mass index (BMI) percentiles. Their findings, published in the Annals of Behavioral Medicine, suggest sleep could help explain the association between household poverty and BMI.

"We've known for a while that physical activity and diet quality are very strong predictors of weight and BMI," said Covington, the lead author of the article. "I think it's really highlighting that ...

Medications for enlarged prostate linked to heart failure risk

2021-02-22

February 22, 2021 - Widely used medications for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) - also known as enlarged prostate - may be associated with a small, but significant increase in the probability of developing heart failure, suggests a study in The Journal of Urology®, Official Journal of the American Urological Association (AUA). The journal is pub lished in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The risk is highest in men taking a type of BPH medication called alpha-blockers (ABs), rather than a different type called 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), according to the new research by D. Robert Siemens, MD, and ...

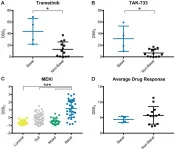

Oncotarget: MEK is a promising target in the basal subtype of bladder cancer

2021-02-22

Oncotarget recently published in "MEK is a promising target in the basal subtype of bladder cancer" by Merrill, et al. which reported that while many resources exist for the drug screening of bladder cancer cell lines in 2D culture, it is widely recognized that screening in 3D culture is more representative of in vivo response.

To address the need for 3D drug screening of bladder cancer cell lines, the authors screened 17 bladder cancer cell lines using a library of 652 investigational small-molecules and 3 clinically relevant drug combinations in 3D cell culture.

Their goal was to identify compounds and classes of compounds with efficacy in bladder cancer.

Utilizing ...

Biological assessment of world's rivers presents incomplete but bleak picture

2021-02-22

An international team of scientists, including two from Oregon State University, conducted a biological assessment of the world's rivers and the limited data they found presents a fairly bleak picture.

"For the places that we have data, the situations are not really that good. There are many species that are declining, threatened or endangered," said Bob Hughes, co-author of the paper and a courtesy associate professor in Oregon State's Department of Fisheries and Wildlife. "But for most of the globe, there just is little rigorous data."

The work by Hughes and the ...

Study quantifying parachute science in coral reef research shows it's 'still widespread'

2021-02-22

By analyzing 50 years' worth of coral reef biodiversity studies, researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 22 have quantified the practice of "parachute science," which happens when international scientists, typically from higher-income countries, conduct field studies in another, typically lower-income country, without engaging with local researchers. They found that institutions from several lower-middle- and upper-middle-income countries with abundant coral reefs produced less research than institutions based in high-income countries with fewer or in some cases no reefs. They also found that host-nation scientists (scientists from the nations where field research was conducted) were ...

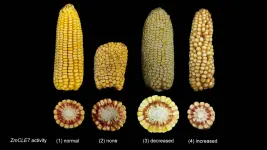

Tweaking corn kernels with CRISPR

2021-02-22

Corn--or maize--has changed over thousands of years from weedy plants that make ears with less than a dozen kernels to the cobs packed with hundreds of juicy kernels that we see on farms today. Powerful DNA-editing techniques such as CRISPR can speed up that process. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor David Jackson and his postdoctoral fellow Lei Liu collaborated with University of Massachusetts Amherst Associate Professor Madelaine Bartlett to use this highly specific technique to tinker with corn kernel numbers. Jackson's lab is one of the first to apply CRISPR to corn's very complex ...

Ghost particle from shredded star reveals cosmic particle accelerator

2021-02-22

Tracing back a ghostly particle to a shredded star, scientists have uncovered a gigantic cosmic particle accelerator. The subatomic particle, called a neutrino, was hurled towards Earth after the doomed star came too close to the supermassive black hole at the centre of its home galaxy and was ripped apart by the black hole's colossal gravity. It is the first particle that can be traced back to such a 'tidal disruption event' (TDE) and provides evidence that these little understood cosmic catastrophes can be powerful natural particle accelerators, as the team led by DESY scientist Robert Stein reports in the journal Nature Astronomy. The observations also demonstrate the power of exploring the cosmos via ...

'Mini brain' organoids grown in lab mature much like infant brains

2021-02-22

A new study from UCLA and Stanford University researchers finds that three-dimensional human stem cell-derived 'mini brain' organoids can mature in a manner that is strikingly similar to human brain development.

For the new study, published in Nature Neuroscience February 22, senior authors Dr. Daniel Geschwind of UCLA and Dr. Sergiu Pasca of Stanford University conducted extensive genetic analysis of organoids that had been grown for up to 20 months in a lab dish. They found that these 3D organoids follow an internal clock that guides their maturation in sync with the timeline of human development.

"This is novel -- Until now, nobody has grown and characterized these organoids for this amount of time, nor shown they will recapitulate human brain development in a laboratory environment ...

New dating techniques reveal Australia's oldest known rock painting, and it's a kangaroo

2021-02-22

A two-metre-long painting of a kangaroo in Western Australia's Kimberley region has been identified as Australia's oldest intact rock painting.

Using the radiocarbon dating of 27 mud wasp nests, collected from over and under 16 similar paintings, a University of Melbourne collaboration has put the painting at 17,500 and 17,100 years old.

"This makes the painting Australia's oldest known in-situ painting," said Postdoctoral Researcher Dr Damien Finch who pioneered the exciting new radiocarbon technique.

"This is a significant find as through these initial estimates, we can understand something of the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

How did humans develop sharp vision? Lab-grown retinas show likely answer

Sour grapes? Taste, experience of sour foods depends on individual consumer

At AAAS, professor Krystal Tsosie argues the future of science must be Indigenous-led

From the lab to the living room: Decoding Parkinson’s patients movements in the real world

Research advances in porous materials, as highlighted in the 2025 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

Sally C. Morton, executive vice president of ASU Knowledge Enterprise, presents a bold and practical framework for moving research from discovery to real-world impact

Biochemical parameters in patients with diabetic nephropathy versus individuals with diabetes alone, non-diabetic nephropathy, and healthy controls

[Press-News.org] Politics and the brain: Attention perks up when politicians break with party linesfMRI study shows stronger neurological responses for politically incongruent positions