(Press-News.org) WASHINGTON -- Researchers have developed a new sensor that could allow practical and low-cost detection of low concentrations of methane gas. Measuring methane emissions and leaks is important to a variety of industries because the gas contributes to global warming and air pollution.

"Agricultural and waste industries emit significant amounts of methane," said Mark Zondlo, leader of the Princeton University research team that developed the sensor. "Detecting methane leaks is also critical to the oil and gas industry for both environmental and economic reasons because natural gas is mainly composed of methane."

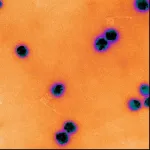

In The Optical Society (OSA) journal Optics Express, researchers from Princeton University and the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory demonstrate their new gas sensor, which uses an interband cascade light emitting device (ICLED) to detect methane concentrations as low as 0.1 parts per million. ICLEDs are a new type of higher-power LED that emits light at mid-infrared (IR) wavelengths, which can be used to measure many chemicals.

"We hope that this research will eventually open the door to low-cost, accurate and sensitive methane measurements," said Nathan Li, first author of the paper. "These sensors could be used to better understand methane emissions from livestock and dairy farms and to enable more accurate and pervasive monitoring of the climate crisis."

Building a less expensive sensor

Laser-based sensors are currently the gold standard for methane detection, but they cost between USD 10,000 and 100,000 each. A sensor network that detects leaks across a landfill, petrochemical facility, wastewater treatment plant or farm would be prohibitively expensive to implement using laser-based sensors.

Although methane sensing has been demonstrated with mid-IR LEDs, performance has been limited by the low light intensities generated by available devices. To substantially improve the sensitivity and develop a practical system for monitoring methane, the researchers used a new ICLED developed by Jerry Meyer's team at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory.

"The ICLEDs we developed emit roughly ten times more power than commercially available mid-IR LEDs had generated, and could potentially be mass-produced," said Meyer. "This could enable ICLED-based sensors that cost less than USD 100 per sensor."

To measure methane, the new sensor measures infrared light transmitted through clean air with no methane and compares that with transmission through air that contains methane. To boost sensitivity, the researchers sent the infrared light from the high-power ICLED through a 1-meter-long hollow-core fiber containing an air sample. The inside of the fiber is coated with silver, which causes the light to reflect off its surfaces as it travels down the fiber to the photodetector at the other end. This allows the light to interact with additional molecules of methane in the air resulting in higher absorption of the light.

"Mirrors are commonly used to bounce light back and forth multiple times to increase sensor sensitivity but can be bulky and require precise alignment," said Li. "Hollow core fibers are compact, require low volumes of sample gas and are mechanically flexible."

Measuring up to laser-based sensors

To test the new sensor, the researchers flowed known concentrations of methane into the hollow core fiber and compared the infrared transmission of the samples with state-of-the-art laser-based sensors. The ICLED sensor was able to detect concentrations as low as 0.1 parts per million while showing excellent agreement with both calibrated standards and the laser-based sensor.

"This level of precision is sufficient to monitor emissions near sources of methane pollution," said Li. "An array of these sensors could be installed to measure methane emissions at large facilities, allowing operators to affordably and quickly detect leaks and mitigate them."

The researchers plan to improve the design of the sensor to make it practical for long-term field measurements by investigating ways to increase the mechanical stability of the hollow-core fiber. They will also study how extreme weather conditions and changes in ambient humidity and temperature might affect the system. Because most greenhouse gases, and many other chemicals, can be identified by using mid-IR light, the methane sensor could also be adapted to detect other important gases.

INFORMATION:

Paper: N. Li, L. Tao, H. Yi, C. S. Kim, M. Kim, C. L. Canedy, C. D. Merritt, W. W. Bewley, I. Vurgaftman, J. R. Meyer, M. A. Zondlo, "Methane detection using an interband-cascade LED coupled to a hollow-core fiber," Opt. Express, 29, 5, 7221-7231 (2021).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.415724

About Optics Express

Optics Express reports on scientific and technology innovations in all aspects of optics and photonics. The bi-weekly journal provides rapid publication of original, peer-reviewed papers. It is published by The Optical Society (OSA) and led by Editor-in-Chief James Leger of the University of Minnesota, USA. Optics Express is an open-access journal and is available at no cost to readers online at OSA Publishing.

About The Optical Society

Founded in 1916, The Optical Society (OSA) is the leading professional organization for scientists, engineers, students and business leaders who fuel discoveries, shape real-life applications and accelerate achievements in the science of light. Through world-renowned publications, meetings and membership initiatives, OSA provides quality research, inspired interactions and dedicated resources for its extensive global network of optics and photonics experts. For more information, visit osa.org.

Media Contact:

mediarelations@osa.org

A new study suggests that a hormone known to prevent weight gain and normalize metabolism can also help maintain healthy muscles in mice. The findings present new possibilities for treating muscle-wasting conditions associated with age, obesity or cancer, according to scientists from the University of Southern California Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

The research, published this month in the American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism, addresses the related problems of age and obesity-induced muscle loss, conditions which can lead to increased risk of falls, diabetes and other negative health impacts. It also adds to a growing number of findings describing beneficial effects of MOTS-c, ...

Scientists at the University of Adelaide have challenged the common assumption that genetic diversity of a species is a key indicator of extinction risk.

Published in the journal PNAS, the scientists demonstrate that there is no simple relationship between genetic diversity and species survival. But, Dr Joao Teixeira and Dr Christian Huber from the University of Adelaide's School of Biological Sciences conclude, the focus shouldn't be on genetic diversity anyway, it should be on habitat protection.

"Nature is being destroyed by humans at a rate never seen before," says computational biologist Dr Huber. "We burn ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Scientists from around the world have published more than 87,000 papers about coronavirus between the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and October 2020, a new analysis shows.

Even given the importance of the pandemic, researchers were surprised by the huge number of studies and other papers that scientists produced on the subject in such a short time.

"It is an astonishing number of publications - it may be unprecedented in the history of science," said Caroline Wagner, co-author of the study and associate professor in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs at The Ohio State University.

"Nearly all of the scientific community around the world turned its attention to this one issue."

Wagner conducted the analysis with Xiaojing Cai from Zhejiang University in ...

A team of researchers designed and manufactured a new sodium-ion conductor for solid-state sodium-ion batteries that is stable when incorporated into higher-voltage oxide cathodes. This new solid electrolyte could dramatically improve the efficiency and lifespan of this class of batteries. A proof of concept battery built with the new material lasted over 1000 cycles while retaining 89.3% of its capacity--a performance unmatched by other solid-state sodium batteries to date.

Researchers detail their findings in the Feb. 23, 2021 issue of Nature Communications.

Solid state batteries hold the promise of safer, cheaper, and longer lasting batteries. Sodium-ion chemistries are particularly promising because sodium is low-cost and abundant, as opposed ...

ROCKVILLE, MD - Coronaviruses exploit our cells so they can make copies of themselves inside us. After they enter our cells, they use our cell machinery to make unique tools of their own that help them generate these copies. By understanding the molecular tools that are shared across coronaviruses, there is potential to develop treatments that can not only work in the current COVID-19 pandemic, but in future coronavirus outbreaks as well. Rockefeller University researchers in the labs of Tarun Kapoor and Shixin Liu, including postdoctoral associate ...

ROCKVILLE, MD - A tenth of all intensive care unit patients worldwide, and many critical patients with COVID-19, have acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Therapeutic hypothermia, an intentional cooling of the body, has been suggested as a way to improve ARDS. New research by Chiara Autilio and colleagues in the lab of Jesus Perez-Gil at the Complutense University of Madrid shows not only how therapeutic hypothermia works in the lungs at the molecular level, but also why it could be successfully applied to ARDS. Autilio and her colleagues' work was published in Nature Scientific Reports in January 2021 and will be presented ...

ROCKVILLE, MD - The remarkable genetic scissors called CRISPR/Cas9, the discovery that won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, sometimes cut in places that they are not designed to target. Though CRISPR has completely changed the pace of basic research by allowing scientists to quickly edit genetic sequences, it works so fast that it is hard for scientists to see what sometimes goes wrong and figure out how to improve it. Julene Madariaga Marcos, a Humboldt postdoctoral fellow, and colleagues in the lab of Professor Ralf Seidel at Leipzig University in Germany, found a way to analyze the ultra-fast movements of CRISPR enzymes, which will help researchers understand how they recognize their target sequences in hopes of improving the specificity. Madariaga Marcos will present ...

New compound targets neurons that initiate voluntary movement

After 60 days of treatment, diseased brain cells look like healthy cells

More research needed before clinical trial can be initiated

CHICAGO and EVANSTON--- Northwestern University scientists have identified the first compound that eliminates the ongoing degeneration of upper motor neurons that become diseased and are a key contributor to ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), a swift and fatal neurodegenerative disease that paralyzes its victims.

In addition to ALS, upper motor neuron degeneration also results in other motor neuron diseases, such as hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS).

In ALS, movement-initiating nerve cells in the brain (upper motor neurons) and muscle-controlling ...

According to a 2017 UCLA study, students with ADHD make up about 6% of the college student population and represent the most common type of disability supported by college disability offices. But are these students receiving enough academic support from their institutions? Despite ADHD being prevalent among college students, there has been little research focused on how having ADHD impacts the transition to college and ongoing academic success. Until now.

New research from George DuPaul, professor of school psychology and associate dean for research in Lehigh University's College of Education, and colleagues confirms students with ADHD face consequential challenges in succeeding and completing ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Younger, smaller trees that comprise much of North America's eastern forests have increased their seed production under climate change, but older, larger trees that dominate forests in much of the West have been less responsive, a new Duke University-led study finds.

Declines in these trees' seed production, or fecundity, could limit western forests' ability to regenerate following the large-scale diebacks linked to rising temperatures and intensifying droughts that are now occurring in many states and provinces.

This continental divide, reported for the ...