(Press-News.org) COLUMBUS, Ohio - Scientists from around the world have published more than 87,000 papers about coronavirus between the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and October 2020, a new analysis shows.

Even given the importance of the pandemic, researchers were surprised by the huge number of studies and other papers that scientists produced on the subject in such a short time.

"It is an astonishing number of publications - it may be unprecedented in the history of science," said Caroline Wagner, co-author of the study and associate professor in the John Glenn College of Public Affairs at The Ohio State University.

"Nearly all of the scientific community around the world turned its attention to this one issue."

Wagner conducted the analysis with Xiaojing Cai from Zhejiang University in China and Caroline Fry of the University of Hawai'i. The study was published online this month in the journal Scientometrics.

The researchers searched for coronavirus-related articles in several scientific databases and found that 4,875 articles were produced on the issue between January and mid-April of 2020. That rose to 44,013 by mid-July and 87,515 by the start of October.

Wagner compared research on coronavirus to the attention given to nanoscale science, which was one of the hottest topics in science during the 1990s.

It took more than 19 years to go from 4,000 to 90,000 scientific articles on that topic, she said.

"Coronavirus research reached that level in about five months," she said.

This new study was an update to one the researchers published in July in PLOS ONE.

In the earlier study, the researchers found that China and the United States led the world in coronavirus research during the early months of the pandemic.

This new study showed that China's contributions dropped off significantly after infection rates in the country fell. From Jan. 1 to April 8, Chinese scientists were involved in 47% of all worldwide publications on coronavirus. That dropped to only 16% from July 13 to Oct. 5.

Similar results were found in other countries when infection levels dropped among their populations.

"That surprised us a bit," Wanger said.

It may be that government funding for research on the issue dropped dramatically in countries like China when the pandemic no longer posed as large of a threat.

"At the beginning of the pandemic, governments flooded scientists with funding for COVID research, probably because they wanted to look like they were responding," she said. "It may be that when the threat went down, so did the funding."

In China, the work was also slowed by a government requirement that officials approve all articles related to COVID-19, Wagner said. Political leaders were concerned about how China, as the source of the virus, appeared to the rest of the world.

Scientists in the United States were involved in 23% of all worldwide coronavirus studies at the beginning of the pandemic and about 33% from July to October, the last period covered in this study.

The new study found that the size of teams on coronavirus research projects, which had already started to get smaller in the first study, continued to drop.

That was unexpected, Wagner said. She and colleagues had anticipated team sizes would slowly get larger as the pandemic continued and researchers had more time to plan and figure out what was happening.

"We attribute this continued decline to the need for speedy results as pandemic infections grew rapidly," Wagner said. "Smaller teams make it easier to work quickly."

The rate of international collaborations also continued to drop, the study found. Part of the reason was practical: Travel bans made it impossible for researchers to meet. This particularly hurt the formation of new collaborations among scientists, which almost always begin face-to-face, Wagner said.

But there may have also been a political component, she said, particularly in U.S.-China collaborations.

The Chinese government's requirement of study review probably hurt. In addition, the U.S. government has given more scrutiny to Chinese researchers in the United States, which may have led some scientists to forgo partnerships.

"We need to figure out a way to restart these collaborations as we move into the post-COVID period," Wagner said. "International cooperation is crucial for the scientific enterprise."

INFORMATION:

Contact:

Caroline Wagner,

Wagner.911@osu.edu

Written by Jeff Grabmeier,

614-292-8457;

Grabmeier.1@osu.edu

A team of researchers designed and manufactured a new sodium-ion conductor for solid-state sodium-ion batteries that is stable when incorporated into higher-voltage oxide cathodes. This new solid electrolyte could dramatically improve the efficiency and lifespan of this class of batteries. A proof of concept battery built with the new material lasted over 1000 cycles while retaining 89.3% of its capacity--a performance unmatched by other solid-state sodium batteries to date.

Researchers detail their findings in the Feb. 23, 2021 issue of Nature Communications.

Solid state batteries hold the promise of safer, cheaper, and longer lasting batteries. Sodium-ion chemistries are particularly promising because sodium is low-cost and abundant, as opposed ...

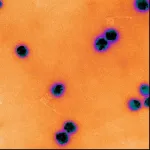

ROCKVILLE, MD - Coronaviruses exploit our cells so they can make copies of themselves inside us. After they enter our cells, they use our cell machinery to make unique tools of their own that help them generate these copies. By understanding the molecular tools that are shared across coronaviruses, there is potential to develop treatments that can not only work in the current COVID-19 pandemic, but in future coronavirus outbreaks as well. Rockefeller University researchers in the labs of Tarun Kapoor and Shixin Liu, including postdoctoral associate ...

ROCKVILLE, MD - A tenth of all intensive care unit patients worldwide, and many critical patients with COVID-19, have acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Therapeutic hypothermia, an intentional cooling of the body, has been suggested as a way to improve ARDS. New research by Chiara Autilio and colleagues in the lab of Jesus Perez-Gil at the Complutense University of Madrid shows not only how therapeutic hypothermia works in the lungs at the molecular level, but also why it could be successfully applied to ARDS. Autilio and her colleagues' work was published in Nature Scientific Reports in January 2021 and will be presented ...

ROCKVILLE, MD - The remarkable genetic scissors called CRISPR/Cas9, the discovery that won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, sometimes cut in places that they are not designed to target. Though CRISPR has completely changed the pace of basic research by allowing scientists to quickly edit genetic sequences, it works so fast that it is hard for scientists to see what sometimes goes wrong and figure out how to improve it. Julene Madariaga Marcos, a Humboldt postdoctoral fellow, and colleagues in the lab of Professor Ralf Seidel at Leipzig University in Germany, found a way to analyze the ultra-fast movements of CRISPR enzymes, which will help researchers understand how they recognize their target sequences in hopes of improving the specificity. Madariaga Marcos will present ...

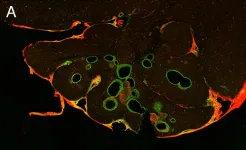

New compound targets neurons that initiate voluntary movement

After 60 days of treatment, diseased brain cells look like healthy cells

More research needed before clinical trial can be initiated

CHICAGO and EVANSTON--- Northwestern University scientists have identified the first compound that eliminates the ongoing degeneration of upper motor neurons that become diseased and are a key contributor to ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), a swift and fatal neurodegenerative disease that paralyzes its victims.

In addition to ALS, upper motor neuron degeneration also results in other motor neuron diseases, such as hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) and primary lateral sclerosis (PLS).

In ALS, movement-initiating nerve cells in the brain (upper motor neurons) and muscle-controlling ...

According to a 2017 UCLA study, students with ADHD make up about 6% of the college student population and represent the most common type of disability supported by college disability offices. But are these students receiving enough academic support from their institutions? Despite ADHD being prevalent among college students, there has been little research focused on how having ADHD impacts the transition to college and ongoing academic success. Until now.

New research from George DuPaul, professor of school psychology and associate dean for research in Lehigh University's College of Education, and colleagues confirms students with ADHD face consequential challenges in succeeding and completing ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Younger, smaller trees that comprise much of North America's eastern forests have increased their seed production under climate change, but older, larger trees that dominate forests in much of the West have been less responsive, a new Duke University-led study finds.

Declines in these trees' seed production, or fecundity, could limit western forests' ability to regenerate following the large-scale diebacks linked to rising temperatures and intensifying droughts that are now occurring in many states and provinces.

This continental divide, reported for the ...

In recent years, researchers have discovered ways to remove specific fears from the brain, increase one's own confidence, or even change people's preferences, by using a combination of artificial intelligence and brain scanning technology. Their technique could lead to new treatments for patients with conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), phobias or anxiety disorders.

But while this technique is extremely promising, in some individuals it remains unsuccessful. Why are there such differences in outcome? Better understanding how the brain can self-regulate its own activity patterns would go a long way toward establishing the technique for clinical use. The researchers who spearheaded this technique have thus released a unique dataset ...

Peer review/Experimental study/Animals

Propranolol, a drug that is efficacious against infantile haemangiomas ("strawberry naevi", resembling birthmarks), can also be used to treat cerebral cavernous malformations, a condition characterised by misshapen blood vessels in the brain and elsewhere. This has been shown by researchers at Uppsala University in a new study published in the scientific journal Stroke.

"Up to now, there's been no drug treatment for these patients, so our results may become hugely important for them," says Peetra Magnusson of the University's Department of Immunology, Genetics and Pathology, who headed the study.

Cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs, also called cavernous angiomas or cavernomas) are vascular lesions ...

DALLAS, Feb. 23, 2021 — Women face many female-specific risks for heart disease and stroke, including pregnancy, physical and emotional stress, sleep patterns and many physiological factors, according to multiple studies highlighted in this year’s Go Red for Women® special issue of the Journal of the American Heart Association, published online today.

“Although cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in men and women, women are less likely to be diagnosed and receive preventive care and aggressive treatment compared to men,” said Journal of the American Heart Association Editor-in-Chief Barry London, M.D., Ph.D., Ph.D., the Potter Lambert Chair in Internal Medicine, director of the division ...