(Press-News.org) Inflammatory lung diseases such as asthma, COPD and, most recently, COVID-19, have proven difficult to treat. Current therapies reduce symptoms and do little to stop such diseases from continuing to damage the lungs. Much research into treating chronic inflammatory diseases has focused on blocking chemicals called cytokines, which trigger cascades of molecular events that fuel damaging inflammation.

Now, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have found that such cytokines can drive inflammation in more ways than previously understood, perhaps revealing new routes to potential treatments for chronic inflammatory conditions.

A new study demonstrates that in addition to raining down directly into tissues and triggering damaging events, cytokines can come packaged in tiny compartments called exosomes, making the packaged cytokines extremely difficult to detect and nearly impossible to study without specialized instruments. Not being able to study these exosomes means scientists could be missing important strategies to treat or prevent inflammatory disease.

The study, in JCI Insight, also demonstrates that understanding how these inflammatory cytokines are packaged can reveal new ways to block them, preventing lung disease from developing, at least in mice.

"In trying to understand and better treat inflammatory disease in patients, scientists have focused heavily on blocking cytokines, which we know are key players in setting off inflammatory processes and keeping them smoldering," said senior author Jennifer Alexander-Brett, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. "How a particular family of cytokines gets out of cells to trigger inflammation has been a mystery that has stymied the field for a long time. At the same time, people started to recognize that these structures called exosomes are doing something, though it was unclear what. They're small, difficult to isolate and easily overlooked. But with new technology, we're starting to understand that key cytokines can be packaged in exosomes in ways that completely change the way we would target them to develop anti-inflammatory therapies."

Based on prior work from Alexander-Brett, Michael J. Holtzman, MD, the Selma and Herman Seldin Professor of Medicine, and other investigators at Washington University, it has long been known that a specific cytokine called IL-33 is a central player in the development of chronic lung diseases, such as COPD and asthma. Indeed, this cytokine also is implicated in arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, hepatitis, heart failure, inflammation of the central nervous system and cancer. But how it triggers inflammation was unknown. The new research shows that IL-33 is released into the airway, packaged with an exosome. Complicating matters further, IL-33 doesn't travel inside the exosome; it piggybacks on the outside.

With a new understanding of the packaging, the researchers tried a different method to block the inflammatory signaling of IL-33. They studied mice that develop lung disease due to inhaling a type of fungus; the disease, mimics, for example, the development of asthma due to an inhaled allergen. The researchers showed that they could block airway disease from developing in mice exposed to the fungus by treating them with a compound that blocks exosome secretion, rather than IL-33 directly.

"This study opens up many new questions about how cytokine signaling might be different when the cytokine is bound to an exosome," Alexander-Brett said. "It's possible exosome packaging is a key feature of cytokines that are not secreted in the classical way. This new understanding of cytokine signaling could lead to completely different ways of targeting it to treat diseases such as COPD. At the moment, we have no treatments that reverse or even slow COPD. We can only treat symptoms."

Alexander-Brett said that until recently, this type of exosome activity would have been extremely difficult to detect. Her lab has a relatively new instrument called a single-particle interferometric reflectance imaging system (SP-IRIS) that lets her team study exosomes using very small amounts of biological samples.

For asthma and COPD, Alexander-Brett said her lab is seeking more precise ways to block specific exosomes, since a strategy that blocks all of them across the board, as in this mouse study, likely would stop some beneficial processes as well.

"We need more research to find an inhibitor that might block IL-33 from even being incorporated into the exosome, which would theoretically stop the initial trigger of chronic lung disease," Alexander-Brett said. "Ideally, we would like to find something that we could deliver as an inhaled drug that would target the effects to the airway, where it's needed."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant numbers K08 HL121168, R01 HL152245 and T32 HL007317; an Early Career Investigator Award from the American Thoracic Society; a career award for medical scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund; and the fund to retain clinical scientists from the Doris Duke Foundation. Additional support and services were provided by the Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Core, grant number NIDDK P30 DK052574; the Siteman Center Flow Cytometry Core; the Washington University Center for Cellular Imaging, grant number ORIP OD021629; the Washington University Genome Engineering and iPSC Center; and the Pulmonary Morphology Core.

Katz-Kiriakos E, et al. Epithelial IL-33 appropriates exosome trafficking for secretion in chronic airway disease. JCI Insight. Feb. 22, 2021.

Washington University School of Medicine's 1,500 faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals. The School of Medicine is a leader in medical research, teaching and patient care, ranking among the top 10 medical schools in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children's hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

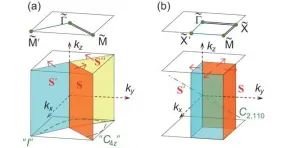

Using the symmetries of the systems, people can define various topological invariants to describe different topological states. The topological materials can be accurately discovered by calculating the topological invariants. Recently, researchers found that irreducible representations and compatibility relationships can be used to determine whether a material is topological nontrivial/trivial insulator (satisfying the compatibility relations) or topological semimetal (violating the compatibility relations), which leads to a large number of topological materials predicted by theoretical calculations. However, Weyl semimetals go beyond this paradigm because the existence of Weyl fermions does not need any symmetry protections (except for lattice translation symmetries). At present, ...

Urban areas are on the rise and changing rapidly in form and function, with spillover effects on virtually all areas of the Earth. The UN estimates that by 2050, 68% of the world's population will reside in urban areas. In the inaugural issue of npj Urban Sustainability, a new Nature Partner Journal out today, a team of leading urban ecologists outlines a practical checklist to guide interventions, strategies, and research that better position urban systems to meet urgent sustainability goals.

Co-author Steward Pickett of Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies explains, "Urban areas shape demographics, ...

By Maria Fernanda Ziegler | Agência FAPESP – Yellow fever was the first human disease to have a licensed vaccine and has long been considered important to an understanding of how epidemics happen and should be combated. It was introduced to the Americas in the seventeenth century, and high death rates have resulted from successive outbreaks since then. Epidemics of yellow fever were associated with the slave trade, the US gold rush and settlement of the Old West, the Haitian Revolution, and construction of the Panama Canal, to cite only a few examples.

Centuries after the disease was first reported in the Americas, an international team of researchers will embark on a groundbreaking study to develop ...

What should researchers do if they encounter a study participant who reports suicidal thoughts?

UIC College of Nursing associate professor Susan Dunn explores this question as lead author of "Suicide Risk Management Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial of Cardiac Patients Reporting Hopelessness," a paper published in the January/February edition of Nursing Research.

Suicide is ranked as the 10th leading cause of death for all ages in the U.S. and can be identified through clinical research, according to the paper.

Although suicide screening tools are widely available for patients in emergency, hospital and primary care settings and ...

The environmental impacts of removing dingoes from the landscape are visible from space, a new UNSW Sydney study shows.

The study, recently published in Landscape Ecology, pairs 32 years' worth of satellite imagery with site-based field research on both sides of the Dingo Fence in the Strzelecki Desert.

The researchers found that vegetation inside the fence - that is, areas without dingoes - had poorer long-term growth than vegetation in areas with dingoes.

"Dingoes indirectly affect vegetation by controlling numbers of kangaroos and small mammals," says Professor Mike Letnic, senior author of the study and researcher at UNSW's Centre ...

Since astronomers captured the bright explosion of a star on February 24, 1987, researchers have been searching for the squashed stellar core that should have been left behind. A group of astronomers using data from NASA space missions and ground-based telescopes may have finally found it.

As the first supernova visible with the naked eye in about 400 years, Supernova 1987A (or SN 1987A for short) sparked great excitement among scientists and soon became one of the most studied objects in the sky. The supernova is located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a small companion galaxy to our own Milky Way, only about 170,000 light-years from Earth.

While astronomers watched debris ...

Unlike the Higgs boson, discovered at CERN's Large Hadron Collider in 2012 after a 40-year quest, the new particle proposed by these researchers is so heavy that it could not be produced directly even in this collider

The University of Granada is among the participants in this major scientific advancement in Theoretical Physics, which could help unravel the mysteries of dark matter

Scientists from the University of Granada (UGR) and the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) have recently published a study in which they endeavour to extend the Standard Model of particle physics (the equivalent of 'the periodic table' for particle physics) and answer some of the questions that this model is unable to answer. Such puzzles include: What ...

This study, published recently in the international journal Insects, was conducted by researchers from the University of Granada, the Doñana Biological Station, and the Biomedical Research Networking Centre for Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP)

Researchers from the University of Granada (UGR), the Doñana Biological Station (EBD-CSIC), and the Biomedical Research Networking Centre for Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP) have carried out the most comprehensive study to date of the eating patterns of the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) and other invasive species of the same genus in Europe. The results of the study were recently published in the international journal Insects.

This research, which reviews ...

With a survival rate of only five years, the most common and aggressive form of primary brain tumor, glioblastoma multiforme, is notoriously hard to treat using current regimens that rely on surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and their combinations.

"Two of the major challenges in the treatment of gliomas include poor transport of chemotherapeutics across the blood brain barrier and undesired side effects of these therapeutics on healthy tissues," said Sheereen Majd, assistant professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Houston. "To get enough medicine across the blood brain barrier, a high dosage ...

Insomnia -- trouble falling asleep, staying asleep or waking up too early -- is a common condition in older adults. Sleeplessness can be exacerbated by osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis causing joint pain. While there are effective therapies for treating insomnia in older adults, many people cannot get the treatment they need because they live in areas with limited access to health care, either in person or over the internet.

With telephones nearly universal among the elderly, however, researchers at the University of Washington and Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute sought to determine if therapy using only a phone connection ...