(Press-News.org) When people hear botulinum toxin, they often think one of two things: a cosmetic that makes frown lines disappear or a deadly poison.

But the "miracle poison," as it's also known, has been approved by the F.D.A. to treat a suite of maladies like chronic migraines, uncontrolled blinking, and certain muscle spasms. And now, a team of researchers from Harvard University and the Broad Institute have, for the first time, proved they could rapidly evolve the toxin in the laboratory to target a variety of different proteins, creating a suite of bespoke, super-selective proteins called proteases with the potential to aid in neuroregeneration, regulate growth hormones, calm rampant inflammation, or dampen the life-threatening immune response called cytokine storm.

"In theory, there is a really high ceiling for the number and type of conditions where you could intervene," said Travis Blum, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology and first author on the study published in Science. The study was the culmination of a collaboration with Min Dong, an associate professor at the Harvard Medical School, and David Liu, the Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, and a core faculty member of the Broad Institute.

Together, the team achieved two firsts: They successfully reprogrammed proteases--enzymes that cut proteins to either activate or deactivate them--to cut entirely new protein targets, even some with little or no similarity to the native targets of the starting proteases, and to simultaneously avoid engaging their original targets. They also started to address what Blum called a "classical challenge in biology": designing treatments that can cross into a cell. Unlike most large proteins, botulinum toxin proteases can enter neurons in large numbers, giving them a wider reach that makes them all the more appealing as potential therapeutics.

Now, the team's technology can evolve custom proteases with tailor-made instructions for which protein to cut. "Such a capability could make 'editing the proteome' feasible," said Liu, "in ways that complement the recent development of technologies to edit the genome."

Current gene-editing technologies often target chronic diseases like sickle cell anemia, caused by an underlying genetic error. Correct the error, and the symptoms fade. But some acute illnesses, like neurological damage following a stroke, aren't caused by a genetic mistake. That's where protease-based therapies come in: The proteins can help boost the body's ability to heal something like nerve damage through a temporary or even one-time treatment.

Scientists have been eager to use proteases to treat disease for decades. Unlike antibodies, which can only attack specific alien substances in the body, proteases can find and attach to any number of proteins, and, once bound, can do more than just destroy their target. They could, for example, reactivate dormant proteins.

"Despite these important features, proteases have not been widely adopted as human therapeutics," said Liu, "primarily because of the lack of a technology to generate proteases that cleave protein targets of our choosing."

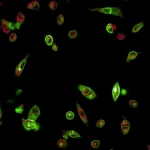

But Liu has a technological ace in his pocket: PACE (which stands for phage-assisted continuous evolution). A Liu lab invention, the platform rapidly evolves novel proteins with valuable features. PACE, Liu said, can evolve dozens of generations of proteins a day with minimal human intervention. Using PACE, the team first taught so-called "promiscuous" proteases--those that naturally target a wide swath of proteins--to stop cutting certain targets and become far more selective. When that worked, they moved on to the bigger challenge: Teaching a protease to only recognize an entirely new target, one outside its natural wheelhouse.

"At the outset," said Blum, "we didn't know if it was even feasible to take this unique class of proteases and evolve them or teach them to cleave something new because that had never been done before." ("It was a moonshot to begin with," said Michael Packer, a previous Liu lab member and an author on the paper). But the proteases outperformed the team's expectations. With PACE, they evolved four proteases from three families of botulinum toxin; all four had no detected activity on their original targets and cut their new targets with a high level of specificity (ranging from 218- to more than 11,000,000-fold). The proteases also retained their valuable ability to enter cells. "You end up with a powerful tool to do intracellular therapy," said Blum. "In theory."

"In theory" because, while this work provides a strong foundation for the rapid generation of many new proteases with new capabilities, far more work needs to be done before such proteases can be used to treat humans. There are other limitations, too: The proteins are not ideal as treatments for chronic diseases because, over time, the body's immune system will recognize them as alien substances and attack and defuse them. While botulinum toxin lasts longer than most proteins in cells (up to three months as opposed to the typical protein lifecycle of hours or days), the team's evolved proteins might end up with shorter lifetimes, which could diminish their effectiveness.

Still, since the immune system takes time to identify foreign substances, the proteases could be effective for temporary treatments. And, to side-step the immune response, the team is also looking to evolve other classes of mammalian proteases since the human body is less likely to attack proteins that resemble their own. Because their work on botulinum toxin proteases proved so successful, the team plans to continue to tinker with those, too, which means continuing their fruitful collaboration with Min Dong, who not only has the required permission from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) to work with botulinum toxin but provides critical perspective on the potential medical applications and targets for the proteases.

"We're still trying to understand the system's limitations, but in an ideal world," said Blum, "we can think about using these toxins to theoretically cleave any protein of interest." They just have to choose which proteins to go after next.

INFORMATION:

A Brazilian study published (http://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-20217-w) in Nature Communications shows that human activities have directly or indirectly caused biodiversity and biomass losses in over 80% of the remaining Atlantic Rainforest fragments.

According to the authors, in terms of carbon storage, the biomass erosion corresponds to the destruction of 70,000 square kilometers (km²) of forest - almost 10 million soccer pitches - or USD 2.3 billion-USD 2.6 billion in carbon credits. "These figures have direct implications for mechanisms of climate change mitigation," they state in the article.

Atlantic Rainforest remnants ...

DALLAS - Feb. 24, 2021 - Using machine learning tools to analyze hundreds of proteins, UT Southwestern researchers have identified a group of biomarkers in blood that could lead to an earlier diagnosis of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and, in turn, more effective therapies sooner.

The identification of nine serum proteins that strongly predict ASD were reported in a study published today by PLOS ONE.

Earlier diagnosis, followed by prompt therapeutic support and intervention, could have a significant impact on the 1 in 59 children diagnosed with autism in the United States. Being able to identify children on the autism spectrum when they are toddlers could make a big difference, says Dwight German, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry at UT Southwestern ...

For decades, climate change researchers and activists have used dramatic forecasts to attempt to influence public perception of the problem and as a call to action on climate change. These forecasts have frequently been for events that might be called "apocalyptic," because they predict cataclysmic events resulting from climate change.

In a new paper published in the International Journal of Global Warming, Carnegie Mellon University's David Rode and Paul Fischbeck argue that making such forecasts can be counterproductive. "Truly apocalyptic forecasts can only ever be observed in their failure--that is the world did not end as predicted," says Rode, adjunct research faculty with the Carnegie Mellon Electricity Industry Center, "and observing ...

Parenthood leads to greater reductions in short-term research productivity for mothers across three disciplines than for fathers, largely explaining the publication gender gap between women and men in academia, according to an analysis of survey data from 3,064 tenure track faculty at PhD-granting universities in the U.S. and Canada. The findings suggest that policies designed to boost workplace flexibility for parents, including easily accessible lactation rooms and affordable childcare, may help to ease the impact of parenthood on mothers in academia, giving them more time for research. While a large body of previous research across academic fields has shown that men tend to publish more papers than women, the reasons for this have remained uncertain. ...

Scientists have found that comparing the ratio of two immune molecules helped predict the likelihood of transplant rejection in 339 patients who received kidney transplants, the only curative treatment for late-stage kidney failure. Their results suggest that monitoring this ratio could help distinguish high-risk patients early on, before long-term organ rejection becomes inevitable, allowing clinicians to intervene accordingly with new treatments. Kidney transplants often grant immediate benefits to patients with end-stage kidney disease, but long-term outcomes are mixed, as 35% of transplant recipients lose their new kidney within ...

Cancer cells can experience stress. They have to contend with attacks by the immune system or with anti-cancer therapeutics. If they attempt to colonize other tissues, they have to break away from the extracellular matrix, enter the bloodstream and survive during the travel through the body. Then exit and start building a new colony. The ability of cells to adapt their properties to face all the challenges they encounter is called plasticity. In epithelial solid tumors, including the very common lung, breast, colon and pancreatic cancers, tumor cells plasticity hijacks a cellular development process known as epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

EMT is commonly associated to kinases - enzymes that act like a switch, turning biochemical ...

Targeted radiation is often used to study and treat diverse cancer types. A multidisciplinary research team based at the University of Chicago Medicine has recently focused on a type of cell that releases a protein that enhances resistance to cancer therapies and promotes tumor progression.

The study focused on Ter cells, which are extra medullary erythroid precursers that secrete the neuropeptide artemin. In the study, published February 24, 2020, in Science Translational Medicine, the researchers showed that local tumor radiotherapy, systemic immunotherapy or the combination of both treatments were able to deplete Ter cells in the spleen, reduce artemin production and limit tumor progression both in the locally irradiated tumors as well as outside ...

Researchers believe they have closed the case of what killed the dinosaurs, definitively linking their extinction with an asteroid that slammed into Earth 66 million years ago by finding a key piece of evidence: asteroid dust inside the impact crater.

Death by asteroid rather than by a series of volcanic eruptions or some other global calamity has been the leading hypothesis since the 1980s, when scientists found asteroid dust in the geologic layer that marks the extinction of the dinosaurs. This discovery painted an apocalyptic picture of dust from the vaporized asteroid and rocks from impact circling the planet, blocking ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Politicization of the COVID-19 pandemic had a powerful influence over adherence to social distancing guidelines in the United States and why people did, or did not, comply during the lockdown days, a new study has found.

The analysis boiled down to whom study participants trusted most: scientists or President Donald Trump.

"People who expressed a great deal of faith in President Trump, who thought he was doing an effective job of guiding us through the pandemic, were less likely to socially distance," said Russell Fazio, senior author of the study and a professor ...

Ultra-fast, cheap LAMP-based COVID tests could be performed by non-experts at work and in public spaces, giving results in under an hour

INFORMATION:

Article Title: "Ultra-rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2 in public workspace environments"

Funding: This project was made possible through the support of a grant from Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry, LLC, The funder provided support in the form of salaries and supplies for authors OY, ZY, JM, and BO, but did not have any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The specific ...