(Press-News.org) Medical researchers have long understood that a pregnant mother's diet has a profound impact on her developing fetus's immune system and that babies -- especially those born prematurely -- who are fed breast milk have a more robust ability to fight disease, suggesting that even after childbirth, a mother's diet matters. However, the biological mechanisms underlying these connections have remained unclear.

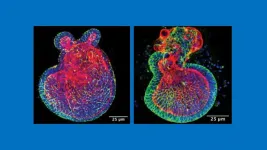

Now, in a study published Feb. 15, 2021, in the journal Nature Communications, a Johns Hopkins Medicine research team reports that pregnant mice fed a diet rich in a molecule found abundantly in cruciferous vegetables -- such as broccoli, Brussels sprouts and cauliflower -- gave birth to pups with stronger protection against necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). NEC is a dangerous inflammatory condition that destroys a newborn's intestinal lining, making it one of the leading causes of mortality in premature infants.

The team also found that breast milk from these mothers continued to confer immunity against NEC in their offspring.

Seen in as many as 12% of newborn babies weighing less than 3.5 pounds at birth, NEC is a rapidly progressing gastrointestinal emergency in which normally harmless gut bacteria invade the underdeveloped wall of the premature infant's colon, causing inflammation that can ultimately destroy healthy tissue at the site. If enough cells become necrotic (die) so that a hole is created in the intestinal wall, the bacteria can enter the bloodstream and cause life-threatening sepsis.

In earlier mouse studies, researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine showed that NEC results when the underdeveloped intestinal lining in premature infants produces higher-than-normal amounts of a protein called toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). TLR4 in full-term babies binds with bacteria in the gut and helps keep the microbes in check. However, in premature infants, TLR4 can act like an immune system switch, with excess amounts of the protein mistakenly directing the body's defense mechanism against disease to attack the intestinal wall instead.

"Based on this understanding, we designed our latest study to see if indole-3-carbinole, or I3C for short, a chemical compound common in green leafy vegetables and known to switch off the production of TLR4, could be fed to pregnant mice, get passed to their unborn children and then protect them against NEC after birth," says study senior author David Hackam, M.D., Ph.D., surgeon-in-chief at Johns Hopkins Children's Center and professor of surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "We also wanted to determine if I3C in breast milk could maintain that protection as the infants grow."

In the first of three experiments, Hackam and his colleagues sought to induce NEC in 7-day old mice, half of which were born from mothers fed I3C derived from broccoli during their pregnancies and half from mothers fed a diet without I3C. They found that those born from mothers given I3C throughout gestation were 50% less likely to develop NEC, even with their immune systems still immature at one week after birth.

The second experiment examined whether breast milk with I3C could continue to provide infant mice with protection against NEC. To do this, the researchers used mice genetically bred without the binding site on intestinal cells for I3C known as the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR).

When AHR-lacking pups were given breast milk from mice fed a diet containing I3C, they could not process the compound. Therefore, they developed severe NEC 50% more frequently than infant mice that had the I3C receptor.

The researchers say this shows in mice -- and suggests in humans -- that AHR must be activated to protect babies from NEC and that what a mother eats during breastfeeding -- in this case, I3C -- can impact the ability of her milk to bolster an infant's developing immune system.

In confirmatory studies, Hackam and his colleagues looked at the amounts of AHR in human tissue obtained from infants undergoing surgery for severe NEC. They found significantly lower than normal levels of the receptor, suggesting that reduced AHR predisposes infants to the disease.

Finally, the researchers searched for a novel drug that could be given to pregnant women to optimize AHR's positive effect and reduce the risk of NEC in the event of premature birth. After screening in pregnant mice a variety of compounds already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for other clinical uses, the researchers observed that one, which they called A18 (clinically known as lansoprazole, a drug approved for the treatment of gastrointestinal hyperacidity), activates the I3C receptor, limits TLR4 signaling and prevents gut bacteria from infiltrating the intestinal wall.

To show the relevance of what they saw in mice, the researchers tested A18 in the laboratory on human intestinal tissue removed from patients with NEC and found the drug produced similar protective results.

"These findings enable us to imagine the possibility of developing a maternal diet that can not only boost an infant's overall growth, but also enhance the immune system of a developing fetus and, in turn, reduce the risk of NEC if the baby is born prematurely," says Hackam.

INFORMATION:

Along with Hackam, the Johns Hopkins Medicine team members are Peng Lu, Yukihiro Yamaguchi, William Fulton, Sanxia Wang, Qinjie Zhou, Hongpeng Jia, Mark Kovler, Andres Gonzalez Salazar, Maame Sampah, Thomas Prindle Jr. and Chhinder Sodhi. Peter Wipf at the University of Pittsburgh also participated in the study.

The research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01GM078238, R01DK117186 and T32 DK00771322, and the Garrett Fund for Surgical Research.

Hackam, Wang, Sodhi and Lu have filed a patent application for the use of AHR agonists in the prevention and treatment of NEC. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

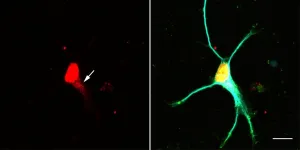

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as various forms of senile dementia or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), have one thing in common: large amounts of certain RNA-protein complexes (snRNPs) are produced and deposited in the nerve cells of those affected - and this hinders the function of the cells. The overproduction is possibly caused by a malfunction in the assembly of the protein complexes.

How the production of these protein complexes is regulated was unknown until now. Researchers from Martinsried and Würzburg in Bavaria, Germany, have solved the puzzle and now report on it in the open access journal Nature Communications. They describe in detail a signaling pathway that prevents the overproduction of snRNPs when they are not needed. The results should ...

A diet rich in human food may be wreaking havoc on the health of urban coyotes, according to a new study by University of Alberta biologists.

The research team from the Faculty of Science examined the stomach contents, gut microbiome and overall health of nearly 100 coyotes in Edmonton's capital region. Their results also show coyotes that consume more human food have more human-like gut bacteria--with potential impact on their nutrition, immune function and, based on similar findings in dogs, even behaviour.

"If eating human food disturbs the 'natural' coyote gut bacteria, it is possible that eating human food has the potential to affect all ...

The answer to the age-old mystery of the evolutionary origins of vertebrate eyes may lie in hagfish, according to a new study by biologists at the University of Alberta.

"Hagfish eyes can help us understand the origins of human vision by expanding our understanding of the early steps in vertebrate eye evolution," explained lead author Emily Dong, who conducted the research during her graduate studies with Ted Allison, a professor in the Faculty of Science and member of the U of A's Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute. "Our findings solidify the hagfish's place among vertebrates and open the door to further research to uncover the finer details ...

Blocking seizures after a head injury could slow or prevent the onset of dementia, according to new research by University of Alberta biologists.

"Traumatic brain injury is a major risk factor for dementia, but the reason this is the case has remained mysterious," said Ted Allison, co-author and professor in the Department of Biological Sciences in the Faculty of Science. "Through this research, we have discovered one important way they are linked--namely, post-injury seizures."

"There is currently no treatment for the long-term effects of traumatic brain injury, which includes developing dementia," added lead author Hadeel Alyenbaawi, who recently completed her PhD dissertation on this topic in the Department of Medical Genetics in the Faculty ...

INFORMS Journal Management Science Study Key Takeaways:

Changing an employee's hours during their shift, typically by having them stay longer, hurts restaurant revenue.

Checks for parties handled by servers who'd been asked to stay longer during their shift dropped by 4.4%, on average.

Servers asked to stay longer reduced the effort spent on upselling and cross-selling additional menu items.

CATONSVILLE, MD, February 25, 2021 - Short notice versus no advance notice makes a huge difference when it comes to employee scheduling in the restaurant industry. New research in the INFORMS journal Management Science finds checks for parties handled by servers who were asked (with ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - In many cases, unions in Europe have helped nonunionized workers whose jobs are precarious, according to new Cornell University research.

In "Dualism or Solidarity? Conditions for Union Success in Regulating Precarious Work," published in December in the European Journal of Industrial Relations, the researchers surveyed academic articles to see how often they would find evidence of unions helping nonunionized workers or helping only their own members, and which conditions were associated with each outcome.

The paper was co-authored by Laura Carver, M.S. 20, and Virginia Doellgast, associate ...

On a low-lying island in the Caribbean, the future of the critically endangered Bahama Oriole just got a shade brighter. A new study led by researchers at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) estimates the population of these striking black and yellow birds at somewhere between 1300 and 2800 individuals in the region they surveyed, suggesting the overall population is likely several thousand. Older studies estimated the entire population at fewer than 300, so the new results indicate there are at least 10 times as many Bahama Orioles as previously understood. The research ...

A group of crustaceans called amphipods can accelerate as fast as a bullet--literally, according to a new study by biologists at the University of Alberta and Duke University.

This study shows that a tiny and unusual species is responsible for making the fastest repeatable movements yet known for any animal in water.

"The high speeds of these repeatable movements reach nearly 30 metres per second or more than 100 kilometres per hour," explained Richard Palmer, professor emeritus in the Department of Biological Sciences and co-author on the study.

"They have the highest accelerations of any animal in water, reaching more than 0.5 million metres per second squared, which is close to the acceleration of ...

Glycomics researchers at the University of Alberta and CHU Sainte-Justine have reported a discovery that could lead to new treatments for cardiovascular disease.

The researchers identified a new mechanism responsible for the buildup of plaque on artery walls, a process known as atherosclerosis. This plaque, made up of fats, cholesterol and other substances, can restrict blood flow and is a major factor in cardiovascular disease.

"We identified a new mechanism underlying atherosclerosis," explained Chris Cairo, professor in the Department of Chemistry and co-lead author of the new study. "We also demonstrated that this can be addressed pharmacologically. Using inhibitors ...

Key takeaways

Opioid prescribing guideline is unique, taking into account each patient's perception of pain, rather than prescribing opioids based on type of operation.

Surgeons play a pivotal role in minimizing opioid use in their patients by setting expectations for pain management.

Opioid disposal rates dramatically increased because surgeons told patients about specific FDA-compliant methods for pill disposal, the location of a convenient pharmacy drop box, and made a reminder phone call.

CHICAGO (February 25, 2021): A prescribing guideline tailored to patients' specific needs reduced the number of opioid pills prescribed after major surgery with researchers reporting ...