(Press-News.org) A computer network closely modelled on part of the human brain is enabling new insights into the way our brains process moving images - and explains some perplexing optical illusions.

By using decades' worth of data from human motion perception studies, researchers have trained an artificial neural network to estimate the speed and direction of image sequences.

The new system, called MotionNet, is designed to closely match the motion-processing structures inside a human brain. This has allowed the researchers to explore features of human visual processing that cannot be directly measured in the brain.

Their study, published in the Journal of Vision, uses the artificial system to describe how space and time information is combined in our brain to produce our perceptions, or misperceptions, of moving images.

The brain can be easily fooled. For instance, if there's a black spot on the left of a screen, which fades while a black spot appears on the right, we will 'see' the spot moving from left to right - this is called 'phi' motion. But if the spot that appears on the right is white on a dark background, we 'see' the spot moving from right to left, in what is known as 'reverse-phi' motion."

The researchers reproduced reverse-phi motion in the MotionNet system, and found that it made the same mistakes in perception as a human brain - but unlike with a human brain, they could look closely at the artificial system to see why this was happening. They found that neurons are 'tuned' to the direction of movement, and in MotionNet, 'reverse-phi' was triggering neurons tuned to the direction opposite to the actual movement.

The artificial system also revealed new information about this common illusion: the speed of reverse-phi motion is affected by how far apart the dots are, in the reverse to what would be expected. Dots 'moving' at a constant speed appear to move faster if spaced a short distance apart, and more slowly if spaced a longer distance apart.

"We've known about reverse-phi motion for a long time, but the new model generated a completely new prediction about how we experience it, which no-one has ever looked at or tested before," said Dr Reuben Rideaux, a researcher in the University of Cambridge's Department of Psychology and first author of the study.

Humans are reasonably good at working out the speed and direction of a moving object just by looking at it. It's how we can catch a ball, estimate depth, or decide if it's safe to cross the road. We do this by processing the changing patterns of light into a perception of motion - but many aspects of how this happens are still not understood.

"It's very hard to directly measure what's going on inside the human brain when we perceive motion - even our best medical technology can't show us the entire system at work. With MotionNet we have complete access," said Rideaux.

Thinking things are moving at a different speed than they really are can sometimes have catastrophic consequences. For example, people tend to underestimate how fast they are driving in foggy conditions, because dimmer scenery appears to be moving past more slowly than it really is.

The researchers showed in a previous study that neurons in our brain are biased towards slow speeds, so when visibility is low they tend to guess that objects are moving more slowly than they actually are.

Revealing more about the reverse-phi illusion is just one example of the way that MotionNet is providing new insights into how we perceive motion. With confidence that the artificial system is solving visual problems in a very similar way to human brains, the researchers hope to fill in many gaps in current understanding of how this part of our brain works.

Predictions from MotionNet will need to be validated in biological experiments, but the researchers say that knowing which part of the brain to focus on will save a lot of time.

Rideaux and his study co-author Dr Andrew Welchman are part of Cambridge's Adaptive Brain Lab, where a team of researchers is examining the brain mechanisms underlying our ability to perceive the structure of the world around us.

INFORMATION:

Over many decades now, traditional drug discovery methods have steadily improved at keeping diseases at bay and cancer in remission. And for the most part, it's worked well.

But it hasn't worked perfectly.

A lab on UNLV's campus has been a hub of activity in recent years, playing a significant role in a new realm of drug discovery -- one that could potentially provide a solution for patients who have run out of options.

"It's starting to get to the point where we've kind of taken traditional drug discovery as far as we can, and we really need something new," said UNLV biochemist Gary Kleiger.

Traditional drug discovery involves what is called the small molecule approach. To attack a protein that's causing disease in a cancer cell, for instance, ...

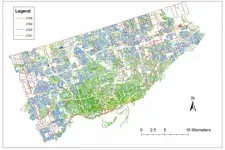

With COVID-19 making it vital for people to keep their distance from one another, the city of Toronto undertook the largest one-year expansion of its cycling network in 2020, adding about 25 kilometres of temporary bikeways.

Yet, the benefits of helping people get around on two wheels go far beyond facilitating physical distancing, according to a recent study by three University of Toronto researchers that was published in the journal Transport Findings.

University of Toronto Engineering PhD candidate Bo Lin, as well as professors Shoshanna Saxe and Timothy Chan used ...

Ithaca, NY--Famous for their uncanny ability to imitate other birds and even mechanical devices, researchers find that Australia's Superb Lyrebird also uses that skill in a totally unexpected way. Lyrebirds imitate the panicked alarm calls of a mixed-species flock of birds while males are courting and even while mating with a female. These findings are published in the journal Current Biology.

"The male Superb Lyrebird creates a remarkable acoustic illusion," says Anastasia Dalziell, currently a Cornell Lab of Ornithology Associate and recent Cornell Lab Rose Postdoctoral Fellow, now at the ...

URBANA, Ill. - Food waste is a major problem in the U.S., and young adults are among the worst culprits. Many of them attend college or university and live on campus, making dining halls a prime target for waste reduction efforts. And a simple intervention can make a big difference, a University of Illinois study shows.

Shifting from round to oval plates with a smaller surface area can significantly reduce food waste in dining halls, says Brenna Ellison, associate professor in the Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics (ACE) and co-author on the study.

"Americans waste about 31% of the food that is available at the retail and consumer levels," Ellison says. "All-you-can-eat ...

West Virginia University scientists used MRI scans to show what happens when ultrasound waves target a specific area of Alzheimer's patient's brains. They concluded that this treatment may induce an immunological healing response, a potential breakthrough for a disease that accounts for up to 80% of all dementia cases.

Rashi Mehta, a researcher with the WVU School of Medicine and Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, led the study that appears in the journal Radiology.

"Focused ultrasound is an innovative technique and new way of approaching brain diseases, including Alzheimer's disease," said Mehta, an associate professor ...

New research in mice published today in the journal Scientific Reports strengthens the growing scientific consensus regarding the role of the gut microbiome in neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's disease.

The study, led by researchers at Oregon Health & Science University, found a correlation between the composition of the gut microbiome and the behavioral and cognitive performance of mice carrying genes associated with Alzheimer's. The mice carried the human amyloid precursor protein gene with dominant Alzheimer's mutations generated by scientists in Japan.

The study further suggests a relationship between microbes in the digestive tract ...

A widespread field search for a rare Australian native bee not recorded for almost a century has found it's been there all along - but is probably under increasing pressure to survive.

Only six individual were ever found, with the last published record of this Australian endemic bee species, Pharohylaeus lactiferus (Colletidae: Hylaeinae), from 1923 in Queensland.

"This is concerning because it is the only Australian species in the Pharohylaeus genus and nothing was known of its biology," Flinders University researcher James Dorey says in a new scientific paper in the journal Journal of Hymenoptera Research.

The ...

Immunologists at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital have mapped the previously unknown biological machinery by which the immune system generates T cells that kill bacteria, viruses and tumor cells.

The findings have multiple implications for how the adaptive immune system responds to infections to generate such memory T cells. The experiments revealed mechanisms that inhibit development of the long-lived memory T cells that continually renew to protect the body over time. Blocking these inhibitory mechanisms with pharmacological or genetic approaches could boost protective immunity against infection and cancers.

The researchers also discovered a subtype of memory T cells that they named terminal effector prime cells. Mapping the pathway that controls these cells raises the possibility ...

(Boston)--What if you could improve your heart health and brain function by changing your diet? Boston University School of Medicine researchers have found that by eating more plant-based food such as berries and green leafy vegetables while limiting consumption of foods high in saturated fat and animal products, you can slow down heart failure (HF) and ultimately lower your risk of cognitive decline and dementia.

Heart failure (HF) affects over 6.5 million adults in the U.S. In addition to its detrimental effects on several organ systems, presence of HF is associated with higher risk of cognitive decline and dementia. Similarly, changes in cardiac structure ...

When building a nest, previous experience raising chicks will influence the choices birds make, according to a new study by University of Alberta scientists.

The results show that birds that have successfully raised families stick with tried-and-true methods when building their nests, whereas less successful birds will try something new.

"We found that when presented with a choice between a familiar material, coconut fibre, and a never-before-encountered material, white string, zebra finches who had successfully raised chicks preferred to stick with the same material they had previously used. Birds who failed to raise chicks built nests with equal amounts of familiar and novel material," explained ...