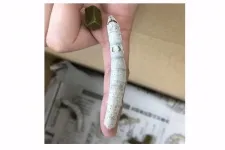

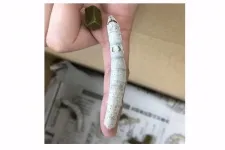

Changing the silkworm's diet to spin stronger silk

2021-02-26

(Press-News.org) Tohoku University researchers have produced cellulose nanofiber (CNF) synthesized silk naturally through a simple tweak to silkworms' diet. Mixing CNF with commercially available food and feeding the silkworms resulted in a stronger and more tensile silk.

The results of their research were published in the journal Materials and Design on February 1, 2021.

"The idea for our research came to us when we realized the flow-focusing method by which silkworms produce silk is optimal for the nanofibril alignment of CNF," said Tohoku University materials engineer Fumio Narita and co-author of the study.

Silk is usually associated with clothes. But its usage is incredibly diverse thanks to its strength and elastic properties. Its biocompatibility makes it even safe to use inside the human body.

Because of this, researchers have been investigating ways to further strengthen silk. Processes investigated thus far, however, require the use of toxic chemicals that are harmful to humans and the environment.

Cellulose nanofibers--plant derived fibers that have been refined to the micro-level-- show promise in synthesizing low-cost, lightweight, high strength, and sustainable nanocomposites such as silk.

However, previous CNF based synthesized materials have demonstrated few mechanical improvements even with the benefit of expensive equipment due to the lack of nanofibril alignment.

In contrast, silkworms produce silk in a flow-focused method. Silk is dispersed via their salivary glands, orientating the fibrils along the flow direction and thus enabling better nanofibril alignment.

In the present study, silkworm larvae were divided into three groups and reared on food containing differing amounts of CNF content. The research group performed strength tests on the drawn silk fibers which were found to be about 2.0 times stronger than the silk from non-CNF fed silkworms.

"Our findings demonstrate an environmentally friendly way to produce sustainable biomaterials by simply using the CNF as bait," said Narita.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-26

An open-source platform, OpenEP co-developed by researchers from the School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences at King's College London has been made available to advance research on atrial fibrillation, a condition characterised by an irregular and often fast heartbeat. It can cause significant symptoms such as breathlessness, palpitations and fatigue, as well as being a major contributor to stroke and heart failure.

Current research into the condition involves the interpretation of large amounts of clinical patient data using software written by individual ...

2021-02-26

The centre is part of the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR). With the help of microscopy and artificial intelligence, the "E-Morph" test reliably identifies substances that can have oestrogen-like or even opposing effects, according to the research team's report in the specialist journal "Environment International". "E-Morph is a milestone on the way to, one day, replacing animal experiments currently required to detect hormone-like effects," says BfR President Prof. Dr. Dr. Andreas Hensel.

Link to the specialist publication (ScienceDirect):

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412021000350

Link ...

2021-02-26

A number of brain areas change their activity before we execute a planned voluntary movement. A new study by Umeå University identifies a novel function of this preparatory neural activity, highlighting another mechanism the nervous system can use to achieve its goals.

Voluntary movements are prepared before they are executed. For example, such 'preparation' occurs in the period between seeing a coffee cup and starting to reach for it. Neurons in many areas of the brain change their activity during movement preparation in ways that reflect different aspects of ...

2021-02-26

Eminent scientists warn that key ecosystems around Australia and Antarctica are collapsing, and propose a three-step framework to combat irreversible global damage.

Their report, authored by 38 Australian, UK and US scientists from universities and government agencies, is published today in the international journal Global Change Biology. Researchers say I heralds a stark warning for ecosystem collapse worldwide, if action if not taken urgently.

Lead author, Dr Dana Bergstrom from the Australian Antarctic Division, said that the project emerged from a conference inspired by her ecological research in polar environments.

"I was seeing unbelievably rapid, widespread dieback in the alpine tundra of World Heritage-listed Macquarie Island and started wondering if this ...

2021-02-26

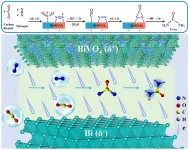

Converting both nitrogen (N2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) into value-added urea molecules via C-N coupling reaction is a promising method to solve the problem of excessive CO2 emissions.

Compared with huge energy consumption industrial processes, the electrochemical urea synthesis provides an appealing route under mild conditions. However, it still faces challenges of low catalytic activity and selectivity.

A research team led by Prof. ZHANG Guangjin from the Institute of Process Engineering (IPE) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences fabricated Bi-BiVO4 Mott-Schottky heterostructure catalysts for efficient urea synthesis at ambient conditions.

This work was published in Angewandte Chemie International ...

2021-02-26

The Korea Institute of Machinery and Materials (KIMM) successfully developed all-round gripper* technology, enabling robots to hold objects of various shapes and stiffnesses. With the new technology, a single gripper can be used to handle different objects such as screwdrivers, bulbs, and coffee pots, and even food with delicate surfaces such as tofu, strawberries, and raw chicken. It is expected to expand applications in contact-free services such as household chores, cooking, serving, packaging, and manufacturing.

*Gripper: A device that enables robots to hold and handle objects, ...

2021-02-26

Memphis, Tenn. (February 25, 2021) - Early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease has been shown to reduce cost and improve patient outcomes, but current diagnostic approaches can be invasive and costly. A recent study, published in the Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, has found a novel way to identify a high potential for developing Alzheimer's disease before symptoms occur.

Ray Romano, PhD, RN, completed the research as part of his PhD in the Nursing Science Program at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center College of Graduate Health Sciences. Dr. Romano conducted the research through the joint laboratory of Associate ...

2021-02-26

DETROIT (February 25, 2021) - Researchers at Henry Ford Health System, as part of a national asthma collaborative, have identified a gene variant associated with childhood asthma that underscores the importance of including diverse patient populations in research studies.

The study is published in the print version of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

For 14 years researchers have known that a casual variant for early onset asthma resides on chromosome 17, which holds one of the most highly replicated and significant genetic associations with asthma. Henry Ford researchers acknowledged they would not have identified it in this study ...

2021-02-26

ROCKVILLE, MD - Scientists are still a long way from being able to treat Alzheimer's Disease, in part because the protein aggregates that can become brain plaques, a hallmark of the disease, are hard to study. The plaques are caused by the amyloid beta protein, which gets misshapen and tangled in the brain. To study these protein aggregates in tissue samples, researchers often have to use techniques that can further disrupt them, making it difficult to figure out what's going on. But new research by Vrinda Sant, a graduate student, and Madhura Som, a recent PhD graduate, in the lab of Ratnesh Lal at the University of California, San Diego, provides a new technique for studying amyloid beta and could be useful in future Alzheimer's treatments. Sant and her colleagues will present their research ...

2021-02-26

Our use of social media, specifically our efforts to maximize "likes," follows a pattern of "reward learning," concludes a new study by an international team of scientists. Its findings, which appear in the journal Nature Communications, reveal parallels with the behavior of animals, such as rats, in seeking food rewards.

"These results establish that social media engagement follows basic, cross-species principles of reward learning," explains David Amodio, a professor at New York University and the University of Amsterdam and one of the paper's authors. "These findings may help us understand why social media comes to dominate daily life for many people and provide clues, borrowed from research on reward learning and addiction, to how troubling online engagement may ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Changing the silkworm's diet to spin stronger silk