(Press-News.org) DETROIT (February 25, 2021) - Researchers at Henry Ford Health System, as part of a national asthma collaborative, have identified a gene variant associated with childhood asthma that underscores the importance of including diverse patient populations in research studies.

The study is published in the print version of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.

For 14 years researchers have known that a casual variant for early onset asthma resides on chromosome 17, which holds one of the most highly replicated and significant genetic associations with asthma. Henry Ford researchers acknowledged they would not have identified it in this study without a diverse patient population that included African Americans, many from the metro Detroit area.

"This study is one of the best examples that demonstrates diversity matters in genetic research," said L. Keoki Williams, M.D., MPH, the study's senior author and co-Director of Henry Ford's Center for Individualized and Genomic Medicine Research. "African Americans have greater variation in their genome due to their African ancestry and this allowed us to pin-point a variant on chromosome 17 which has eluded asthma researchers for over a decade."

In an accompanying editorial written by researchers at the Harvard Medical School, the authors wrote that divergent genealogical histories can facilitate gene discovery. "In a time when our society is attempting to confront the ills of racial discrimination, including the ongoing racial disparities in healthcare, it is imperative that future studies are more inclusive to ensure that all peoples benefit equally in the post-genome era."

According to the National Center for Health Statistics, more than 41 million Americans had asthma in 2019, of which 18.5% were children less than 18 years of age. As a group, African Americans have some of the highest rates of asthma in the U.S. - 17.6% vs. 9.3% for African American children and non-Hispanic white children, respectively, and 15.2% vs. 13.8% for African American adults and non-Hispanic white adults, respectively.

The Henry Ford-led study was conducted in collaboration with researchers Esteban Burchard, M.D., MPH, at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) and Hakon Hakonarson, M.D., Ph.D., at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP). It was part of the Asthma Translational Genomics Collaborative and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute's Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program, a nationwide effort to use cutting-edge genetic technologies to better understand common, yet complex, diseases.

The study is believed to be the largest to date using whole genome sequencing for asthma research. It included 5,630 African American participants with and without asthma from the Henry Ford, UCSF and CHOP cohorts. Participants from Henry Ford were part of the Study of Asthma Phenotypes and Pharmacogenomic Interactions by Race-Ethnicity, or SAPPHIRE.

"African Americans have been represented in less than 3% of these types of studies, yet make up 13% of the U.S. population," said Hongsheng Gui, Ph.D., a Henry Ford researcher and study co-author. "Another reason to have diverse study populations is that many of the genetic risk markers found in one population group don't replicate in other population groups. However, the variant that we found appears to confer the same magnitude of asthma risk in both African Americans and non-Hispanic white Americans."

The variant that was identified resides in a gene called gasdermin-B, abbreviated GSDMB. Researchers found that the "protective" variant caused alternative splicing or editing of the final gene, resulting in a messenger RNA sequence missing exons 6 and 7. Researchers believe that this finding will help focus efforts to understand how this particular gene affects a child's risk of developing asthma.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by grants from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the American Asthma Foundation.

About Henry Ford Health System

Founded in 1915 by Henry Ford himself, Henry Ford Health System is a non-profit, integrated health system committed to improving people's lives through excellence in the science and art of healthcare and healing. Henry Ford Health System includes Henry Ford Medical Group, with more than 1,900 physicians and researchers practicing in more than 50 specialties at locations throughout Southeast and Central Michigan. Acute care hospitals include Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, MI and Henry Ford Allegiance Health in Jackson, MI - both Magnet® hospitals; Henry Ford Macomb Hospital; Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital; and Henry Ford Wyandotte Hospital.

The largest of these is Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, a quaternary care research and teaching hospital and Level 1 Trauma Center recognized for clinical excellence in cardiology, cardiovascular surgery, neurology, neurosurgery, and multi-organ transplants. The health system also provides comprehensive, best-in-class care for cancer at the Brigitte Harris Cancer Pavilion, and orthopedics and sports medicine at the William Clay Ford Center for Athletic Medicine - both in Detroit.

As one of the nation's leading academic medical centers, Henry Ford Health System annually trains more than 3,000 medical students, residents, and fellows in more than 50 accredited programs, and has trained nearly 40% of the state's physicians. Our dedication to education and research is supported by nearly $100 million in annual grants from the National Institutes of Health and other public and private foundations.

Henry Ford's not-for-profit health plan, Health Alliance Plan (HAP), provides health coverage for more than 540,000 people.

Henry Ford Health System employs more than 33,000 people, including more than 1,600 physicians, more than 6,600 nurses and 5,000 allied health professionals.

NEWS MEDIA ONLY may contact:

David Olejarz / David.Olejarz@hfhs.org / 313-303-0606

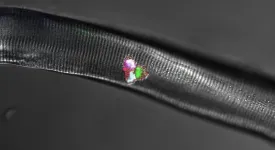

ROCKVILLE, MD - Scientists are still a long way from being able to treat Alzheimer's Disease, in part because the protein aggregates that can become brain plaques, a hallmark of the disease, are hard to study. The plaques are caused by the amyloid beta protein, which gets misshapen and tangled in the brain. To study these protein aggregates in tissue samples, researchers often have to use techniques that can further disrupt them, making it difficult to figure out what's going on. But new research by Vrinda Sant, a graduate student, and Madhura Som, a recent PhD graduate, in the lab of Ratnesh Lal at the University of California, San Diego, provides a new technique for studying amyloid beta and could be useful in future Alzheimer's treatments. Sant and her colleagues will present their research ...

Our use of social media, specifically our efforts to maximize "likes," follows a pattern of "reward learning," concludes a new study by an international team of scientists. Its findings, which appear in the journal Nature Communications, reveal parallels with the behavior of animals, such as rats, in seeking food rewards.

"These results establish that social media engagement follows basic, cross-species principles of reward learning," explains David Amodio, a professor at New York University and the University of Amsterdam and one of the paper's authors. "These findings may help us understand why social media comes to dominate daily life for many people and provide clues, borrowed from research on reward learning and addiction, to how troubling online engagement may ...

Chemical engineering researchers have developed a new catalyst that significantly increases yield in styrene manufacturing, while simultaneously reducing energy use and greenhouse gas emissions.

"Styrene is a synthetic chemical that is used to make a variety of plastics, resins and other materials," says Fanxing Li, corresponding author of the work and Alcoa Professor of Chemical Engineering at North Carolina State University. "Because it is in such widespread use, we are pleased that we could develop a technology that is cost effective and will reduce the environmental impact of styrene manufacturing." Industry estimates ...

The koala retrovirus (KoRV) is a virus which, like other retroviruses such as HIV, inserts itself into the DNA of an infected cell. At some point in the past 50,000 years, KoRV has infected the egg or sperm cells of koalas, leading to offspring that carry the retrovirus in every cell in their body. The entire koala population of Queensland and New South Wales in Australia now carry copies of KoRV in their genome. All animals, including humans, have gone through similar "germ line" infections by retroviruses at some point in their evolutionary history and contain many ancient retroviruses in their genomes. These retroviruses have, over millions of years, mutated into degraded, inactive forms that are no longer harmful to the host. Since in most animal ...

NARRAGANSETT, R.I. - February 26, 2021 - A team of researchers from the University of Rhode Island's END ...

When a muscle grows, because its owner is still growing too or has started exercising regularly, some of the stem cells in this muscle develop into new muscle cells. The same thing happens when an injured muscle starts to heal. At the same time, however, the muscle stem cells must produce further stem cells - i.e., renew themselves - as their supply would otherwise be depleted very quickly. This requires that the cells involved in muscle growth communicate with each other.

Muscle growth is regulated by the Notch signaling pathway

Two years ago, a team of researchers led by Professor Carmen Birchmeier, head of the Developmental Biology/Signal Transduction ...

A new study shows that a widespread decline in abundance of emergent insects - whose immature stages develop in lakes and streams while the adults live on land - can help to explain the alarming decline in abundance and diversity of aerial insectivorous birds (i.e. preying on flying insects) across the USA. In turn, the decline in emergent insects appears to be driven by human disturbance and pollution of water bodies, especially in streams. This study, published in END ...

Who would have thought that a small basic compound like vitamin B6 in the banana or fish you had this morning may be key to your body's robust response against COVID-19?

Studies have so far explored the benefits of vitamins D and C and minerals like zinc and magnesium in fortifying immune response against COVID-19. But research on vitamin B6 has been mostly missing. Food scientist END ...

HDL cholesterol (high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) or good cholesterol is associated with a decreased risk of cardiovascular disease as it transports cholesterol deposited in the arteries to the liver to be eliminated. This contrasts with the so-called bad cholesterol, LDL (low-density lipoprotein cholesterol), which causes cholesterol to accumulate in the arteries and increases cardiovascular risk. Although drugs that lower bad cholesterol reduce cardiovascular risk, those that raise good cholesterol have not proven effective in reducing the risk of heart disease. This paradox has called into question the ...

Whilst the nation has taken to washing its hands regularly since the start of the pandemic, other individual behaviours, such as cleaning and disinfecting surfaces or social distancing within the home, have proved harder to stick, say the researchers behind the behaviour change website 'Germ Defence'.

In their new study, published today (Friday 26 February 2021) in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, psychologists from the universities of Bath, Bristol and Southampton, warn of the continuing risks of household transmission of COVID-19 and the ongoing importance of breaking chains of transmission now and in the future.

Their research analysed user data of the ...