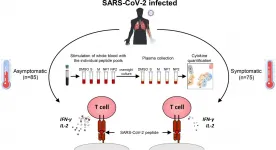

(Press-News.org) By analyzing blood samples from individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2, researchers in Singapore have begun to unpack the different responses by the body's T cells that determine whether or not an individual develops COVID-19. The study, published today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), suggests that clearing the virus without developing symptoms requires T cells to mount an efficient immune response that produces a careful balance of pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules.

Many people infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus do not develop any symptoms, and the infection is cleared by both antibodies and T cells that specifically recognize the virus. In some cases, however, this protective immune response can trigger excessive inflammation that damages tissues and causes many of the symptoms associated with COVID-19.

What determines whether or not an infected individual develops symptoms remains unknown. Some studies have suggested that asymptomatic individuals produce fewer anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies than individuals that develop symptoms. But whether their T cell responses are also reduced was unclear.

"Asymptomatic individuals constitute a variable but often large proportion of infected individuals, and they should hold the key to understanding the immune response capable of controlling the virus without triggering pathological processes," says Antonio Bertoletti, a professor at the Duke-NUS Medical School in Singapore.

Bertoletti and colleagues, including Nina Le Bert, a senior research fellow at Duke-NUS Medical School, and Clarence C. Tam, an assistant professor at the National University of Singapore Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, studied a group of migrant workers who were exposed to SARS-CoV-2 in their dormitories in April 2020. Over the course of six weeks, the researchers took regular blood samples from 85 workers who were infected but remained asymptomatic and compared their T cells to those of 75 patients who were hospitalized with mild to moderate COVID-19.

Surprisingly, the researchers found that, shortly after infection, the frequency of T cells recognizing SARS-CoV-2 was similar in both asymptomatic individuals and COVID-19 patients. "The overall magnitude of T cell responses against different viral proteins was similar in both cohorts," Nina Le Bert says.

However, the T cells of asymptomatic individuals produced greater amounts of two proteins called IFN-γ and IL-2. These signaling proteins, or cytokines, help to coordinate the immune system's response to viruses and other pathogens.

Accordingly, the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 appears to be more coordinated in asymptomatic individuals. Bertoletti and colleagues challenged some of the blood samples with fragments of viral proteins and found that the immune cells of asymptomatic individuals produce a balanced, well-proportioned mix of pro- and anti-inflammatory molecules. In contrast, the immune cells of COVID-19 patients produced a disproportionate amount of proinflammatory molecules.

"Overall, our study suggests that asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals are not characterized by a weak antiviral immunity; on the contrary, they mount a highly efficient and balanced anti-viral cellular response that protects the host without causing any apparent pathology," the researchers say.

The molecular details of this response, and how it safely controls SARS-CoV-2 infections, can now be studied in more detail. However, because most of the participants in the study were male and of Indian/Bangladeshi origin, the researchers caution that their results will need to be confirmed in women and other populations around the world.

INFORMATION:

Le Bert et al. 2021. J. Exp. Med. https://rupress.org/jem/article-lookup/doi/10.1084/jem.20202617?PR

About Journal of Experimental Medicine

Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM) publishes peer-reviewed research on immunology, cancer biology, stem cell biology, microbial pathogenesis, vascular biology, and neurobiology. All editorial decisions on research manuscripts are made through collaborative consultation between professional scientific editors and the academic editorial board. Established in 1896, JEM is published by Rockefeller University Press, a department of The Rockefeller University in New York. For more information, visit jem.org.

Visit our Newsroom, and sign up for a weekly preview of articles to be published. Embargoed media alerts are for journalists only.

Follow JEM on Twitter at @JExpMed and @RockUPress.

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- The rate of suicide among post-9/11 military veterans has been rising for nearly a decade. While there are a number of factors associated with suicide, veterans have unique experiences that may contribute to them thinking about killing themselves.

"Compared to their civilian peers, veterans are more likely to report having experienced traumatic adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) such as physical and emotional abuse," stated Keith Aronson, associate director of the Clearinghouse for Military Family Readiness at Penn State and the Social Science Research Institute ...

LAWRENCE -- A new study from University of Kansas journalism & mass communication researchers examines what influences people to be susceptible to false information about health and argues big tech companies have a responsibility to help prevent the spread of misleading and dangerous information.

Researchers shared a fake news story with more than 750 participants that claimed a deficiency of vitamin B17 could cause cancer. Researchers then measured if how the article was presented -- including author credentials, writing style and whether the article was labeled as "suspicious" or "unverified" -- affected how participants perceived its credibility and whether they would adhere to the article's recommendations or share it on social media. The findings showed that ...

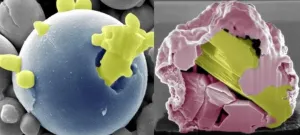

AMES, Iowa - Inspired by nature's work to build spiky structures in caves, engineers at Iowa State University have developed technology capable of recovering pure and precious metals from the alloys in our old phones and other electrical waste.

Using controlled applications of oxygen and relatively low temperatures, the engineers say they can dealloy a metal by slowly moving the most reactive components to the surface where they form stalagmite-like spikes of metal oxides.

That leaves the least-reactive components in a purified, liquid core surrounded by brittle metal-oxide spikes "to create a so-called 'ship-in-a-bottle structure,'" said Martin Thuo, the leader of the research project and an associate professor of materials science and ...

A type of ultrasound scan can detect cancer tissue left behind after a brain tumour is removed more sensitively than surgeons, and could improve the outcome from operations, a new study suggests.

The new ultrasound technique, called shear wave elastography, could be used during brain surgery to detect residual cancerous tissue, allowing surgeons to remove as much as possible.

Researchers believe that the new type of scan, which is much faster to carry out and more affordable than 'gold standard' MRI scans, has the potential to reduce a patient's risk of relapse by cutting the chances that a tumour will grow ...

The amount of green space surrounding children's homes could be important for their risk of developing ADHD. This is shown by new research results from iPSYCH.

A team of researchers from Aarhus University has studied how green space around the residence affects the risk of children and adolescents being diagnosed with ADHD. And the researchers find an association.

"Our findings show that children who have been exposed to less green surroundings in their residential area in early childhood, which we define as lasting up until age five, have an increased risk of receiving an ADHD diagnosis when compared to children who have been surrounded by the highest level of green space," says ...

Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder are the three main eating disorders that 4 out of in 10 individuals living in Western Europe will experience at some point in their lives. In recent years, studies on the genetic basis of anorexia nervosa have highlighted the existence of predisposing genetic markers, which are shared with other psychiatric disorders. By analysing the genome of tens of thousands of British people, a team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), the University Hospitals of Geneva (HUG), King's College London, the University College London, the University of North Carolina (UNC) and The Icahn ...

Research from the University of Kent has led to the development of the MeshCODE theory, a revolutionary new theory for understanding brain and memory function. This discovery may be the beginning of a new understanding of brain function and in treating brain diseases such as Alzheimer's.

In a paper published by Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, Dr Ben Goult from Kent's School of Biosciences describes how his new theory views the brain as an organic supercomputer running a complex binary code with neuronal cells working as a mechanical computer. He explains ...

Gene editing technology will play a vital role in climate-proofing future crops to protect global food supplies, according to scientists at The University of Queensland.

Biotechnologist Dr Karen Massel from UQ's Centre for Crop Science has published a review of gene editing technologies such as CRISPR-Cas9 to safeguard food security in farming systems under stress from extreme and variable climate conditions.

"Farmers have been manipulating the DNA of plants using conventional breeding technologies for millennia, and now with new gene-editing technologies, we can do this with unprecedented safety, precision and speed," Dr Massel said.

"This type of gene editing mimics the way cells repair in nature."

Her review recommended ...

New research from the University of Kent reveals social cohesion with immigration is best ensured through childhood exposure to diversity in local neighbourhoods, leading to acceptance of other groups.

The research, which is published in Oxford Economic Papers, builds on the Nobel Laureate economist Thomas Schelling's Model of Segregation, which showed that a slight preference by individuals and families towards their own groups can eventually result in complete segregation of communities.

Shedding new light on this issue, researchers from Kent's School of Economics have introduced the theory ...

Will we enjoy our work more once routine tasks are automated? - Not necessarily, suggests a recent study

Research conducted at Åbo Akademi University suggests that when routine work tasks are being replaced with intelligent technologies, the result may be that employees no longer experience their work as meaningful.

Advances in new technologies such as artificial intelligence, robotics and digital applications have recently resurrected discussions and speculations about the future of working life. Researchers predict that new technologies will affect, in particular, routine and structured work tasks. According to estimations, 7-35 percent ...