(Press-News.org) As the planet warms, scientists expect that mountain snowpack should melt progressively earlier in the year. However, observations in the U.S. show that as temperatures have risen, snowpack melt is relatively unaffected in some regions while others can experience snowpack melt a month earlier in the year.

This discrepancy in the timing of snowpack disappearance--the date in the spring when all the winter snow has melted--is the focus of new research by scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

In a new study published March 1 in the journal Nature Climate Change, Scripps Oceanography climate scientists Amato Evan and Ian Eisenman identify regional variations in snowpack melt as temperatures increase, and they present a theory that explains which mountain snowpacks worldwide are most "at-risk" from climate change. The study was funded by NOAA's Climate Program Office.

Looking at nearly four decades of observations in the Western U.S., the researchers found that as temperatures rise, the timing of snowpack disappearance is changing most rapidly in coastal regions and the south, with smaller changes in the northern interior of the country. This means that snowpack in the Sierra Nevadas, the Cascades, and the mountains of southern Arizona is much more vulnerable to rising temperatures than snowpack found in places like the Rockies or the mountains of Utah.

The scientists used these historical observations to create a new model for understanding why the timing of snowpack disappearance differs widely across mountain regions. They theorize that changes in the amount of time that snow can accumulate and the amount of time the surface is covered with snow during the year are the critical reasons why some regions are more vulnerable to snowpack melt than others.

"Global warming isn't affecting everywhere the same. As you get closer to the ocean or further south in the U.S., the snowpack is more vulnerable, or more at-risk, due to increasing temperature, whereas in the interior of the continent, the snowpack seems much more impervious, or resilient to rising temperatures," said Evan, lead author of the study. "Our theory tells us why that's happening, and it's basically showing that spring is coming a lot earlier in the year if you're in Oregon, California, Washington, and down south, but not if you're in Colorado or Utah."

Applying this theory globally, the researchers found that increasing temperatures would affect the timing of snowpack melt most prominently in the Arctic, the Alps of Europe, and the southern region of South America, with much smaller changes in the northern interiors of Europe and Asia, including the central region of Russia.

To devise the model that led to these findings, Evan and Eisenman analyzed daily snowpack measurements from nearly 400 sites across the Western U.S managed by the Natural Resources Conservation Service Snowpack Telemetry (SNOTEL) network. They looked at SNOTEL data each year from 1982 to 2018 and focused on changes in the date of snowpack disappearance in the spring. They also examined data from the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR) showing the daily mean surface air temperature and precipitation over the same years for each of these stations.

Using an approach based on physics and mathematics, the model simulates the timing of snowpack accumulation and snowpack melting as a function of temperature. The scientists could then use the model to solve for the key factor that was causing the differences in snowpack warming: time. Specifically, they looked at the amount of time snow can accumulate and the amount of time the surface is covered with snow.

"I was excited by the simplicity of the explanation that we ultimately arrived at," said Eisenman. "Our theoretical model provides a mechanism to explain why the observed snowmelt dates change so much more at some locations than at others, and it also predicts how snowmelt dates will change in the future under further warming."

The model shows that regions with very large swings in temperature between the winter and summer are less susceptible to warming than those where the change in temperature from winter to summer is smaller. The model also shows that regions where the annual mean temperature is closest to 0?C are less susceptible to early melt. The most susceptible regions are ones where the differences between wintertime and summertime temperatures are small, and where the average temperature is either far above, or even far below 0?C.

For example, in an interior mountain region of the U.S. like the Colorado Rockies, where the temperature dips below 0°C for about half the year, an increase of 1°C can lead to a quicker melt by a couple of days--not a huge difference.

However, in a coastal region like the Pacific Northwest, the influence of the ocean and thermal regulation helps keep the winter temperatures a bit warmer, meaning there are fewer days below 0°C in which snow can accumulate. The researchers hypothesize that in the region's Cascade Mountains, a 1°C increase in temperature could result in the snow melting about a month earlier in the season--a dramatic difference.

One of the most "at-risk" regions is the Arctic, where snow accumulates for nine months each year and takes about three months to melt. The model suggests that 1°C warming there would result in a faster melt by about a week--a significant period of time for one of the fastest warming places on Earth.

This study builds upon previous work done by Scripps scientists since the mid-1990s to map out changes in snowmelt timing and snowpacks across the Western U.S. The authors said that a "shrinking" winter--one that is shorter, warmer, and with less overall precipitation--has adverse societal effects because it contributes to a longer fire season. This could have devastating impacts on already fire-prone regions. In California, faster snowpack melt rates have already made forest management more difficult and provided prime conditions for invasive species like the bark beetle to thrive.

INFORMATION:

Funding for this work was provided by NOAA/CPO grant NA17OAR4310163 to the University of California.

For the first time, scientists have assessed how many corals there are in the Pacific Ocean--and evaluated their risk of extinction.

While the answer to "how many coral species are there?" is 'Googleable', until now scientists didn't know how many individual coral colonies there are in the world.

"In the Pacific, we estimate there are roughly half a trillion corals," said the study lead author, Dr Andy Dietzel from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies at James Cook University (Coral CoE at JCU).

"This is about the same number of trees in the Amazon, or ...

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN FRANCISCO

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

Toronto, ON - Children in the United States who have more screen time at ages 9-10 are more likely to develop binge-eating disorder one year later, according to a new national study.

The study, published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders on March 1, found that each additional hour spent on social media was associated with a 62% higher risk of binge-eating disorder one year later. It also found that each additional hour spent watching or streaming television or movies led to a 39% ...

HANOVER, N.H. - March 1, 2020 - During World War II, British intelligence agents planted false documents on a corpse to fool Nazi Germany into preparing for an assault on Greece. "Operation Mincemeat" was a success, and covered the actual Allied invasion of Sicily.

The "canary trap" technique in espionage spreads multiple versions of false documents to conceal a secret. Canary traps can be used to sniff out information leaks, or as in WWII, to create distractions that hide valuable information.

WE-FORGE, a new data protection system designed at Dartmouth's Department ...

Assessing a drug compound by its activity, not simply its structure, is a new approach that could speed the search for COVID-19 therapies and reveal more potential therapies for other diseases.

This action-based focus -- called biological activity-based modeling (BABM) -- forms the core of a new approach developed by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) researchers and others. NCATS is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Researchers used BABM to look for potential anti-SARS-CoV-2 agents whose actions, not their structures, are similar to those of compounds already shown to be effective.

NCATS scientists ...

The hidden social, environmental and health costs of the world's energy and transport sectors is equal to more than a quarter of the globe's entire economic output, new research from the University of Sussex Business School and Hanyang University reveals.

According to analysis carried out by Professor Benjamin K. Sovacool and Professor Jinsoo Kim, the combined externalities for the energy and transport sectors worldwide is an estimated average of $24.662 trillion - the equivalent to 28.7% of global Gross Domestic Product.

The study found that the true cost of coal should be more than twice as high as current prices when factoring in the currently unaccounted ...

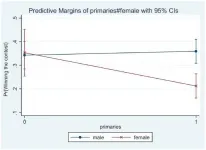

A study by two researchers at the UPF Department of Political and Social Sciences (DCPIS) has examined the effect of selecting party leaders by direct vote by the entire membership (a process known in southern Europe as "primaries" and in English-speaking countries as "one-member-one -vote", OMOV) on the likelihood of a woman winning a leadership competition against male rivals.

Javier Astudillo and Andreu Paneque, a tenured lecturer and PhD with the DCPIS, respectively, and members of the Institutions and Political Actors Research Group, are the authors of the article published recently in the journal ...

TROY, N.Y. -- The era of widespread remote learning brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic requires online testing methods that effectively prevent cheating, especially in the form of collusion among students. With concerns about cheating on the rise across the country, a solution that also maintains student privacy is particularly valuable.

In research published today in npj Science of Learning, engineers from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute demonstrate how a testing strategy they call "distanced online testing" can effectively reduce students' ability to receive help from one another in order to score higher on a test taken at individual homes during social distancing.

"Often in remote online exams, students ...

A group of researchers including Tiago Falótico, a Brazilian primatologist at the University of São Paulo's School of Arts, Sciences and Humanities (EACH-USP), archeologists at Spain's Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES) and University College London in the UK, and an anthropologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, have published an article in the Journal of Archeological Science: Reports describing an analysis of stone tools used by bearded capuchin monkeys (Sapajus libidinosus) that inhabit ...

Researchers at CÚRAM, the SFI Research Centre for Medical Devices based at National University of Ireland Galway, and BIOFORGE Lab, at the University of Valladolid in Spain, have developed an injectable hydrogel that could help repair and prevent further damage to the heart muscle after a heart attack.

The results of their research have just been published in the prestigious journal Science Translational Medicine.

Myocardial infarction or heart disease is a leading cause of death due to the irreversible damage caused to the heart muscle (cardiac tissue) during a heart attack. The regeneration of cardiac tissue is minimal so that the damage caused cannot be repaired by itself. ...

Because walleyes are a cool-water fish species with a limited temperature tolerance, biologists expected them to act like the proverbial "canary in a coal mine" that would begin to suffer and signal when lakes influenced by climate change start to warm. But in a new study, a team of researchers discovered that it is not that simple.

"After analyzing walleye early-life growth rates in many lakes in the upper Midwest over the last three decades, we determined that water clarity affects how growth rates of walleyes change as lakes start to warm," said Tyler Wagner, Penn State adjunct professor of fisheries ecology. ...