(Press-News.org) An impressive body of evidence published this week reveals the answer to a mystery that has puzzled plant scientists for more than 30 years: the role of the molecule suberin in the leaves of some of our most productive crops. This discovery could be the key to engineering better crops and ensuring future food security.

Highly productive crops such as sugarcane, sorghum and maize belong to the type of plants that use the more efficient C4 photosynthetic pathway to transform water, sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2) into sugars.

Scientists have known for a long time that one of key factors that makes C4 photosynthesis more efficient is that they have the capacity to enclose CO2 inside a gas tight compartment in the leaf tissue, making it easier for the inefficient photosynthetic enzyme Rubisco to fix carbon.

"The big question we haven't been able to answer until now is what makes this compartment gas tight so CO2 can't escape?" says lead author Dr Florence Danila, from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Translational Photosynthesis (CoETP) at the Australian National University (ANU).

"Our research provides several pieces of evidence about the responsibility of suberin on making the leaf cells of C4 plants, gas tight. Suberin forms a layer that keeps CO2 gas inside a layer of cells called the bundle sheath. We have grown mutant plants that don't develop this layer and we have seen the deleterious effect this mutation has in their growth and in their capacity to photosynthesise," says Dr Danila, who works at ANU as part of the international C4 Rice Project, led by Oxford University.

This discovery is the result of many years of work, a bit of serendipity and access to modern techniques that were not available until recently, including faster and cheaper genome mapping, high throughput phenotyping, electron microscopy and gas exchange measures.

"We have known for a long time that suberin is in the bundle sheath cells of the C4 plants leaves. However, we didn't have the experimental evidence to prove its essential role for C4 photosynthesis. Now, for the first time, we have been able to see clearly under the microscope, the anatomical differences between plants with and without suberin. The key element in this discovery is that we found a mutant population of green foxtail millet (Setaria viridis) that didn't have the gene that produces suberin," says CoETP's Deputy Director Professor Susanne von Caemmerer, one of the co-authors of this study.

This elusive mutant population was generated in the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) by screening hundreds of plants under low CO2 conditions and then selecting those plants that didn't perform well.

"Using high throughput screening, we identified only three mutants with impaired photosynthetic capacity. We sent the seeds to ANU in Canberra and they grew and analysed them using the electron microscope and gas exchange techniques. To our surprise, one of these mutants was the one that lacked suberin, says Dr Rob Coe, who was in charge of the screening process at IRRI.

Centre Director and co-author of the paper Bob Furbank says that "this is a very exciting discovery, one of the last mechanistic pieces of the C4 photosynthesis puzzle, as Hal Hatch, the discoverer of the C4 pathway noted some time ago".

"It shows that science discoveries can take a long time to be solved and that the recipe for eureka moments like this are the collaborative work of several experts combined with modern technologies, plus a pinch of serendipity. It seems that all the stars were aligned this time for us, but it was certainly a hard nut to crack," he says.

Dr Danila says that the team's next steps involve applying their discovery and new developed methodologies to projects like the C4 rice project that aims to convert rice (a C3 photosynthesis crop) into the more productive C4 path.

"We will also focus on another unsolved mystery: the case of a group of grasses which use C4 photosynthesis but don't have suberin," she says.

INFORMATION:

This research has been funded by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Translational Photosynthesis, which aims to improve the process of photosynthesis to increase the production of major food crops such as sorghum, wheat and rice.

The research started as part of the C4 Rice Project consortium, which comprises the Academia Sinica, Australian National University, Max Planck Institute of Molecular Plant Physiology, Leibniz Institute of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, University of Oxford and Washington State University and is funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to the University of Oxford.

LOS ALAMOS, N.M., March 1, 2021-- A novel computer algorithm that could create a broadly reactive influenza vaccine for swine flu also offers a path toward a pan-influenza vaccine and possibly a pan-coronavirus vaccine as well, according to a new paper published in Nature Communications.

"This work takes us a step closer to a pan-swine flu virus vaccine," said Bette Korber, a computational biologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory and a co-author on the paper. "The hope is to eventually be prepared with an effective and rapid response if another swine flu epidemic begins to spread in humans, but this swine flu vaccine could also be useful in a veterinary setting." The immune responses to the vaccine showed very promising breadth against diverse viral variants. "The same basic principles ...

Nearly everything author Malcolm Gladwell said about how information spreads in his 2000 bestseller "The Tipping Point" is wrong, according to a recent study led by UCLA professor of sociology Gabriel Rossman.

"The main point of 'The Tipping Point' is if you want your idea to spread, you find the most popular person in the center of any given network and you sell them on your idea, and then they'll sell the rest of the world on it," Rossman said.

But Rossman's latest study, recently published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, pokes holes in that widely accepted notion ...

Law enforcement seizures of drugs, particularly marijuana and methamphetamine, dropped at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, then increased significantly in the following months--exceeding pre-pandemic seizure rates and providing clues about the impact of the crisis on substance use, according to a new study in the journal Drug and Alcohol Dependence.

The research was conducted as part of the National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS), which uses real-time surveillance to detect early signals of potential drug epidemics. NDEWS is led by a team of researchers at the University of Florida, New York University, and Florida Atlantic University, ...

While natural disasters and economic recessions traditionally unleash an uptick in child abuse, a new study suggests that cases may have declined in the first months of the pandemic, compared with the same timeframe in previous years.

In the study, led by UCSF Benioff Children's Hospitals and Children's Mercy Kansas City, researchers tracked the number of pediatric inpatients ages 5 and under in 52 children's hospitals nationwide for the first eight months of 2020. They found a steep decline in the number of ER visits and hospital admissions, including those requiring treatment for physical abuse. This started in mid-March - around the time some states issued shelter-in-place ...

A Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet (LMU) in Munich team has shown that slight alterations in transfer-RNA molecules (tRNAs) allow them to self-assemble into a functional unit that can replicate information exponentially. tRNAs are key elements in the evolution of early life-forms.

Life as we know it is based on a complex network of interactions, which take place at microscopic scales in biological cells, and involve thousands of distinct molecular species. In our bodies, one fundamental process is repeated countless times every day. In an operation known as replication, proteins duplicate the genetic ...

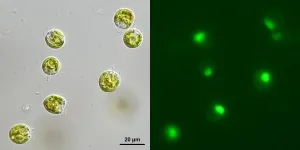

New research suggests that the ability of green algae to eat bacteria is likely much more widespread than previously thought, a finding that could be crucial to environmental and climate science. The work, led by scientists at the American Museum of Natural History, Columbia University, and the University of Arizona, found that five strains of single-celled green algae consume bacteria when they are "hungry," and only when those bacteria are alive. The study is published today in The ISME Journal.

"Traditionally, we think of green algae as being purely photosynthetic organisms, producing their food by soaking in sunlight," said Eunsoo Kim, an associate curator at the American Museum of Natural History and one of the study's corresponding ...

An international team led by Prof. dr habil. Andrzej Niedzielski, an astronomer from the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Torun (Poland), has discovered yet another three extrasolar planets. These planets revolve around the stars that can be called elder sisters of our Sun.

You can read about the astronomers' success in Astronomy and Astrophysics. The prestigious European journal will publish the paper: Tracking Advanced Planetary Systems (TAPAS) with HARPS-N. VII. Elder suns with low-mass companions. Apart from Prof. Andrzej Niedzielski from the NCU Institute of Astronomy, the team which worked on the discovery includes Prof. dr habil. Gracjan Maciejewski, also from the NCU Faculty of Physics, Astronomy and Informatics, Prof. Aleksander Wolszczan (Pennsylvania State ...

For several years now, the biofuels that power cars, jet airplanes, ships and big trucks have come primarily from corn and other mass-produced farm crops. Researchers at USC, though, have looked to the ocean for what could be an even better biofuel crop: seaweed.

Scientists at the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies on Santa Catalina Island, working with private industry, report that a new aquaculture technique on the California coast dramatically increases kelp growth, yielding four times more biomass than natural processes. The technique employs a contraption called the "kelp elevator" ...

Australia's marine World Heritage Sites are among the world's largest stores of carbon dioxide according to a new report from the United Nations, co-authored by an ECU marine science expert.

The UNESCO report found Australia's six marine World Heritage Sites hold 40 per cent of the estimated 5 billion tons of carbon dioxide stored in mangrove, seagrass and tidal marsh ecosystems within UNESCO sites.

The report quantifies the enormous amounts of so-called blue carbon absorbed and stored by those ecosystems across the world's 50 UNESCO marine World Heritage Sites.

Despite covering less ...

Rapid COVID-19 tests are on the rise to deliver results faster to more people, and scientists need an easy, foolproof way to know that these tests work correctly and the results can be trusted. Nanoparticles that pass detection as the novel coronavirus could be just the ticket.

Such coronavirus-like nanoparticles, developed by nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego, would serve as something called a positive control for COVID-19 tests. Positive controls are samples that always test positive. They are run and analyzed right alongside patient samples to verify that COVID-19 tests are working consistently and as intended.

The positive controls developed at UC San Diego offer several advantages over the ones currently used in COVID-19 testing: ...