(Press-News.org) Researchers have captured the first detailed images of newborn babies' lungs as they take their first breaths.

The research, led by the Murdoch Children's Research Institute (MCRI) and published the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, provides a breakthrough in understanding the events around a baby's first breath, why healthy babies cry at birth and provides clues to improving preterm babies' survival chances and long term health outcomes.

About 10 per cent of newborns, and almost all preterm infants, need resuscitation because their lungs do not properly fill with air at birth (a process called lung aeration). Despite this, MCRI Associate Professor David Tingay said that birth was one of the most poorly understood respiratory events in medicine due to the difficulties of imaging a newborn's lungs.

The research involved studying full-term infants born at The Royal Women's Hospital. Researchers used cutting edge-technology, electrical impedance tomography (EIT), where a small silk belt is placed around the infants chest to take highly detailed images deep into the lungs without interfering with parental contact or clinical care. This process allowed the team to generate high resolution images of how air was moving through the lungs for each breath.

Associate Professor Tingay said the technology helped babies in a way that was not possible before.

"Respiratory problems are the most common reason we need to treat babies in intensive care," he said. "This new technology not only allows us to see deep into the lungs but is also the only method we have of continuously imaging the lungs without using radiation or interrupting life-saving care. This study has shown that babies' lungs are far more complicated than traditional monitoring methods had previously suggested."

Associate Professor Tingay said he was currently researching whether using the technology on very preterm babies may help to predict which children would go onto develop lung problems.

Joanna Bezette's daughter, Camilla 'Milly', 14 months, has chronic lung disease after being born at 25 weeks.

"Milly had to be intubated at just eight minutes old," she said. "She spent the next five months in the neonatal intensive care unit relying on various types of respiratory ventilation and having what felt like an endless amount of X-rays. There were times when she had two or three X-rays a day. You just shudder to think of a tiny baby having to go through that.

"It took doctors about a month to get a full picture of just how little and underdeveloped Milly's lungs were. Even today Milly still requires supplementary oxygen when sleeping."

Ms Bezette said it was remarkable to think about the potential of the new lung imaging technology for premmie babies.

"So many families could be spared in future from what we went through in those first few weeks of Milly's life," she said. "To have imaging technology that can detect quickly whether there is problem with a newborn's lungs and that's also not invasive will be of such great comfort."

Associate Professor Tingay said this recent study provided the first detailed description of exactly how lungs fill with air during the first moments after birth.

"Healthy term babies use remarkably complex methods of adapting to air-breathing at birth," he said. "There is a reason why parents, midwives and obstetricians are pleased to hear those first life-affirming cries when a baby is born. Crying is a process that quickly aerates the lung, which is why 80 per cent of all breaths immediately after birth are cries.

"We were amazed to see that expiration is also critically important during those first cries. Just after birth the lung is still at risk of collapsing and the air-spaces can refill with fluid when a baby is breathing out. Babies are remarkably clever, as they breath out after a cry they move gas from well aerated regions to those areas of the lungs that are still filled with fluid preventing collapse. Babies will keep doing this until their lungs are safely filled with air and then they can start breathing normally."

Associate Professor Tingay said doctors lacked strong evidence-based interventions to support breathing after birth, influencing infant deaths, the rate of disease and resource allocation across all health care settings.

"Improving interventions in the delivery room first requires understanding the processes that define success and failure of breathing at birth," he said. "This study has significantly reduced that knowledge gap. We hope that being able to see these unique breathing patterns in the delivery room will tell clinicians when a baby needs resuscitation and also guide how effective that resuscitation is."

INFORMATION:

Researchers from the University of Melbourne, The Royal Children's Hospital, The Royal Women's Hospital, Rostock University Medical Center in Germany, Carleton University in Canada and the University Medical Center Schleswig-Holstein in Germany also contributed to the findings.

Publication: David G Tingay, Olivia Farrell, Jessica Thomson, Elizabeth J Perkins, Prue M Pereira-Fantini, Andreas D Waldmann, Christoph Rüegger, Andy Adler, Peter G Davis, Inéz Frerichs. 'The respiratory complexities during transition to air-breathing at birth,' American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202007-2997OC

Funding:

The study was supported by the Victorian Government Operational Infrastructure Support Program and the National Health and Medical Research Council Centre of Research Excellence (Grant ID 1057514). DGT is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Clinical Career Development Fellowship (Grant ID 1053889). PGD is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant (Grant ID 606789). PGD is supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Practitioner Fellowship (Grant ID 556600).

*The content of this communication is the sole responsibility of MCRI and does not reflect the views of the NHMRC.

Available for interview:

Associate Professor David Tingay, MCRI Group Leader

Neonatal Research

Joanna Bezette, whose daughter, Camilla 'Milly', 14 months, has chronic lung disease

New research from UBC finds that higher life satisfaction is associated with better physical, psychological and behavioural health.

The research, published recently in The Milbank Quarterly, found that higher life satisfaction is linked to 21 positive health and well-being outcomes including:

a 26 per cent reduced risk of mortality

a 46 per cent reduced risk of depression

a 25 per cent reduced risk of physical functioning limitations

a 12 per cent reduced risk of chronic pain

a 14 per cent reduced risk of sleep problem onset

an eight per cent higher likelihood of frequent physical activity

better psychological well-being on ...

If you've ever swatted a mosquito away from your face, only to have it return again (and again and again), you know that insects can be remarkably acrobatic and resilient in flight. Those traits help them navigate the aerial world, with all of its wind gusts, obstacles, and general uncertainty. Such traits are also hard to build into flying robots, but MIT Assistant Professor Kevin Yufeng Chen has built a system that approaches insects' agility.

Chen, a member of the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and the Research Laboratory of Electronics, has developed insect-sized drones with unprecedented dexterity and resilience. The aerial robots ...

Green tea supplements modulate facial development of children with Down syndrome

A new study led by Belgian and Spanish researchers published in Scientific Reports adds evidence about the potential benefits of green tea extracts in Down syndrome. The researchers observed that the intake of green tea extracts can reduce facial dysmorphology in children with Down syndrome when taken during the first three years of life. Additional experimental research in mice confirmed the positive effects at low doses. However, they also found that high doses of the extract can disrupt facial and bone development. More research is needed to fully understand the effects of green tea extracts and therefore they should ...

Imagine a robot.

Perhaps you've just conjured a machine with a rigid, metallic exterior. While robots armored with hard exoskeletons are common, they're not always ideal. Soft-bodied robots, inspired by fish or other squishy creatures, might better adapt to changing environments and work more safely with people.

Roboticists generally have to decide whether to design a hard- or soft-bodied robot for a particular task. But that tradeoff may no longer be necessary.

Working with computer simulations, MIT researchers have developed a concept for a soft-bodied robot that can turn rigid on demand. The approach could enable a new generation of robots that combine the strength and precision of rigid robots with the fluidity and safety of ...

The models used to produce global climate scenarios may overestimate the energy and emission savings from improved energy efficiency, warns new research led by academics at the University of Sussex Business School and the University of Leeds.

In a review of 33 studies, the researchers find that economy wide rebound effects may erode around half of the energy and emission savings from improved energy efficiency.

These rebound effects result from individuals and businesses responding to the benefits of improved energy efficiency - such as cheaper heating, lighting and travel. These responses improve quality-of-life, raise productivity and boost industrial competitiveness, ...

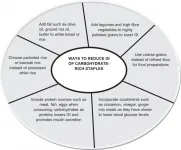

Professor Christiani Jeyakumar Henry, Senior Advisor of Singapore Institute of Food and Biotechnology Innovation (SIFBI), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) and his team have developed a Glycaemic Index (GI) glossary of non-Western foods. The research paper (attached PDF) was published in Nutrition & Diabetes on 6 Jan 2021: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-020-00145-w.

Observational studies have shown that the consumption of low glycaemic index (GI) foods is associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), significantly less insulin resistance and a lower prevalence of the metabolic syndrome. ...

Recently, research team led by academician GUO Guangcan from CAS Key Laboratory of Quantum Information of the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of CAS, has made an important progress in quantum information theory. Prof. LI Chuanfeng and Prof. XIANG Guoyong from the team, cooperated with Dr. Strelstov from University of Warsaw, investigated the imaginary part of quantum theory as a resource, and several important results have been obtained. Relevant results are now jointly published as Editors' Suggestion in Physical Review Letters and Physical Review A.

Complex number is a mathematical ...

It is millions of trillions of times brighter than the sunlight and a whopping 1,000 trillionth of a second, appropriately called the instantaneous light. It is the X-ray Free Electron Laser (XFEL) light that opens a new scientific paradigm. Combining it with AI, an international research team has succeeded in filming and restoring the 3D structure of nanoparticles that share structural similarities with viruses. With the fear of a new pandemic growing around the world due to COVID-19, this discovery is attracting the attention among academic circles for imaging the structure of the virus with both high accuracy and speed.

An international team of researchers from POSTECH, National University of ...

Targeted, efficient and with few side effects: A new method for combating periodontitis could render the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics superfluous. It was developed and tested for the first time by a team from Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg (MLU), the Fraunhofer Institute for Cell Therapy and Immunology IZI and Periotrap Pharmaceuticals GmbH. The aim is to neutralise only bacteria that cause periodontitis while sparing harmless bacteria. The study appeared in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Periodontitis is a common bacterial inflammation of the gums. According to the World Health Organization WHO Oral ...

Ask Eric Weaver about pandemics, and he's quick to remind you of a fact that illustrates the fleeting nature of human memory and the proximal nature of human attention: The first pandemic of the 21st century struck not in 2019, but 2009.

That's when the H1N1/09 swine flu emerged, eventually infecting upwards of 1.4 billion people -- nearly one of every five on the planet at the time. True to the name, swine flus jump to humans from pigs. It's a phenomenon that has been documented more than 400 times since the mid-2000s in the United States alone.

"They're considered the great mixing vessel," said Weaver, associate professor of biological sciences at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. "They're susceptible to their own circulating ...