The researchers sought to identify mutation hotspots, or frequent changes in specific locations of the cancer patients' genetic information. The researchers then used these hotspots to look for whether the same mutations were present in the DNA data of more than 4,500 people who were not known to have a cancer diagnosis. They found that approximately 2 percent of these presumably healthy participants had, at low levels, mutations identical to those frequently observed in the cancer patients.

"Understanding how a disease develops is greatly benefited by studying persons who are currently healthy but are on a trajectory for disease onset," said Clint Mason, PhD, assistant professor of pediatrics at the U of U, who specializes in cancer genomics and bioinformatics and led the study.

Mutations occur throughout the 3 billion bases of DNA that are present in human cells. Many will have no impact on health, yet certain mutations may cause or support development of diseases, including cancer. Therefore, scientists are working to discern which mutations have a significant impact on health. In this study, the researchers sought to understand which mutations are most frequently present in adults and children both with and without blood cancers. They hope this information may illuminate an understanding of these cancers, and further, may potentially be used to identify people who are progressing towards cancer.

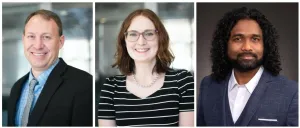

The team of researchers consisted nearly entirely of University of Utah (U of U) faculty and students. Mason was joined by co-first authors Julie Feusier, PhD, a trainee in the department of human genetics and now a postdoctoral fellow at Huntsman Cancer Institute, and Sasi Arunachalam, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow at Huntsman Cancer Institute and now a research associate at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, in performing analyses along with other co-authors.

For the first part of the study, the researchers completed a large data mining analysis to examine published data from 48 cancer studies that reported mutations present in persons who were being diagnosed with leukemia or other hematologic malignancies. Across the 7,430 pediatric and adult cancer patients of those studies, 434 DNA locations were identified as frequently mutated. Then, in a subsequent analysis of many terabytes of publicly available genetic data, the researchers identified these same cancer-relevant mutations at low levels among 83 of the 4,538 persons who were presumably free from cancer.

"When identical mutations are found to be present in a small percentage of blood cells of a healthy person, it may indicate that something abnormal has begun to occur," explained Mason.

This abnormal process (known as clonal hematopoiesis) has previously been found to be increasingly common as people age. As a result, researchers generally focus on the study of adults when investigating this phenomenon. Yet in this study, in addition to adults, the researchers analyzed data from 400 children who were likely to be free from cancer. They found preliminary evidence that early cancer mutations could be detected in this age group.

In an accompanying commentary, to be published by Blood Cancer Discovery in its "In the Spotlight" section, Barbara Spitzer, MD, and Ross Levine, MD, of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, wrote, "This work demonstrates the first evidence that [clonal hematopoiesis] is observed in children outside of those with advanced malignancies." They further commented, "This expansion of the range of hematologic malignancy hotspot mutations goes beyond an improved understanding of the molecular repertoire of hematologic malignancies... More complete knowledge of relevant mutations may increase our detection of patients at highest risk for malignant transformation."

Finding a low-level mutation identical to one that is frequently present at cancer diagnoses could be alarming to a currently healthy person screened for such events. But fortunately, because cancer frequently requires multiple mutations to be present in a sizeable fraction of cells, most persons with a single low-level mutation are not likely to develop cancer for many years or decades--if they develop cancer at all. Large longitudinal studies are needed to identify the timeframe over which specific mutations or combinations of mutations accelerate progression to cancer.

The Utah researchers next hope to determine the stability of mutations identified at younger ages. This will give a preliminary glimpse into their potential to serve as biomarkers for those having greatest risk of cancer. Future intervention studies will require such an identification.

"Our goal has been to help fill in gaps in the understanding of cancer development so that future prevention work can take place more quickly and effectively," said Mason. "We are grateful to have been able to contribute a few puzzle pieces to that monumental effort."

INFORMATION:

The work was funded by the Pediatric Cancer Program, which is supported by the Primary Children's Hospital Foundation, the Intermountain Healthcare Foundation, and the Division of Hematology & Oncology in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Utah. The co-authors were supported by the National Institutes of Health, including the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, the Department of Defense Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program, and Huntsman Cancer Foundation.

Associated Content:

View the full commentary published in In The Spotlight at https://bloodcancerdiscov.aacrjournals.org/content/early/2021/02/26/2643-3230.BCD-21-0025

About University of Utah Health

University of Utah Health provides leading-edge and compassionate care for a referral area that encompasses Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and much of Nevada. A hub for health sciences research and education in the region, U of U Health touts a $408 million research enterprise and trains the majority of Utah's physicians and health care providers at its Colleges of Health, Nursing, and Pharmacy and Schools of Dentistry and Medicine. With more than 20,000 employees, the system includes 12 community clinics and five hospitals. U of U Health is recognized nationally as a transformative health care system and regionally a provider of world-class care.

About Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) at the University of Utah is the official cancer center of Utah. The cancer campus includes a state-of-the-art cancer specialty hospital as well as two buildings dedicated to cancer research. HCI treats patients with all forms of cancer and is recognized among the best cancer hospitals in the country by U.S. News and World Report. As the only National Cancer Institute (NCI)-Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center in the Mountain West, HCI serves the largest geographic region in the country, drawing patients from Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana. More genes for inherited cancers have been discovered at HCI than at any other cancer center in the world, including genes responsible for hereditary breast, ovarian, colon, head, and neck cancers, along with melanoma. HCI manages the Utah Population Database, the largest genetic database in the world, with information on more than 11 million people linked to genealogies, health records, and vital statistics. HCI was founded by Jon M. and Karen Huntsman.