(Press-News.org) A recent analysis of the latest generation of climate models -- known as a CMIP6 -- provides a cautionary tale on interpreting climate simulations as scientists develop more sensitive and sophisticated projections of how the Earth will respond to increasing levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Researchers at Princeton University and the University of Miami reported that newer models with a high "climate sensitivity" -- meaning they predict much greater global warming from the same levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide as other models -- do not provide a plausible scenario of Earth's future climate.

Those models overstate the global cooling effect that arises from interactions between clouds and aerosols and project that clouds will moderate greenhouse gas-induced warming -- particularly in the northern hemisphere -- much more than climate records show actually happens, the researchers reported in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

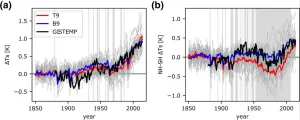

Instead, the researchers found that models with lower climate sensitivity are more consistent with observed differences in temperature between the northern and southern hemispheres, and, thus, are more accurate depictions of projected climate change than the newer models. The study was supported by the Carbon Mitigation Initiative (CMI) based in Princeton's High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI).

These findings are potentially significant when it comes to climate-change policy, explained co-author Gabriel Vecchi, a Princeton professor of geosciences and the High Meadows Environmental Institute and principal investigator in CMI. Because models with higher climate sensitivity forecast greater warming from greenhouse gas emissions, they also project more dire -- and imminent -- consequences such as more extreme sea-level rise and heat waves.

The high climate-sensitivity models forecast an increase in global average temperature from 2 to 6 degrees Celsius under current carbon dioxide levels. The current scientific consensus is that the increase must be kept under 2 degrees to avoid catastrophic effects. The 2016 Paris Agreement sets the threshold to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

"A higher climate sensitivity would obviously necessitate much more aggressive carbon mitigation," Vecchi said. "Society would need to reduce carbon emissions much more rapidly to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and keep global warming below 2 degrees Celsius. Reducing the uncertainty in climate sensitivity helps us make a more reliable and accurate strategy to deal with climate change."

The researchers found that both the high and low climate-sensitivity models match global temperatures observed during the 20th century. The higher-sensitivity models, however, include a stronger cooling effect from aerosol-cloud interaction that offsets the greater warming due to greenhouse gases. Moreover, the models have aerosol emissions occurring primarily in the northern hemisphere, which is not consistent with observations.

"Our results remind us that we should be cautious about a model result, even if the models accurately represent past global warming," said first author Chenggong Wang, a Ph.D. candidate in Princeton's Program in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences. "We show that the global average hides important details about the patterns of temperature change."

In addition to the main findings, the study helps shed light on how clouds can moderate warming both in models and the real world at large and small scales.

"Clouds can amplify global warming and may cause warming to accelerate rapidly during the next century," said co-author Wenchang Yang, an associate research scholar in geosciences at Princeton. "In short, improving our understanding and ability to correctly simulate clouds is really the key to more reliable predictions of the future."

Scientists at Princeton and other institutions have recently turned their focus to the effect that clouds have on climate change. Related research includes two papers by Amilcare Porporato, Princeton's Thomas J. Wu '94 Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the High Meadows Environmental Institute and a member of the CMI leadership team, that reported on the future effect of heat-induced clouds on solar power and how climate models underestimate the cooling effect of the daily cloud cycle.

"Understanding how clouds modulate climate change is at the forefront of climate research," said co-author Brian Soden, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami. "It is encouraging that, as this study shows, there are still many treasures we can exploit from historical climate observations that help refine the interpretations we get from global mean-temperature change."

INFORMATION:

The paper, "Compensation Between Cloud Feedback and Aerosol?Cloud Interaction in CMIP6 Models," was published in the Feb. 28 edition of Geophysical Research Letters. The research was supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (grants NA20OAR4310393 and NA18OAR4310418) and the Carbon Mitigation Initiative based in Princeton University's High Meadows Environmental Institute (HMEI).

Inspired by the eyes of mantis shrimp, researchers have developed a new kind of optical sensor that is small enough to fit on a smartphone but is capable of hyperspectral and polarimetric imaging.

"Lots of artificial intelligence (AI) programs can make use of data-rich hyperspectral and polarimetric images, but the equipment necessary for capturing those images is currently somewhat bulky," says Michael Kudenov, co-corresponding author of a paper on the work and an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at North Carolina State University. "Our work here makes smaller, more user friendly devices possible. And that would allow us to better bring those AI capabilities to bear in fields from astronomy to biomedicine."

In the context of this research, ...

Researchers have analyzed tracking data for 5,775 birds across 39 species of albatrosses and large petrels -- threatened seabirds whose ranges span many countries and the high seas -- to estimate how responsibility for their protection should be distributed among nations and international organizations. The authors note that albatrosses and large petrels from all breeding countries spend much of their time on the high seas, indicating that effectively managing these waters is of global interest. These estimates are critical to inform ongoing United Nations discussions to design a global treaty for conserving biodiversity in the high seas, beyond national jurisdictions, the authors write. Many species of albatrosses and ...

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. - First-year college students are reporting symptoms of depression and anxiety significantly more often than they were before the coronavirus pandemic, according to a study by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The study, embargoed for release until March 3, 2021, at 2 p.m. EST, in the journal PLOS ONE, is based on surveys of 419 Carolina students, and reflects the challenge of colleges nationwide to support student well-being.

The study is unique among the growing reports of COVID-19's toll on mental health: researchers followed the ...

The source of potentially hazardous solar particles, released from the Sun at high speed during storms in its outer atmosphere, has been located for the first time by researchers at UCL and George Mason University, Virginia, USA.

These particles are highly charged and, if they reach Earth's atmosphere, can potentially disrupt satellites and electronic infrastructure, as well as pose a radiation risk to astronauts and people in airplanes. In 1859, during what's known as the Carrington Event, a large solar storm caused telegraphic systems across Europe and America to fail. With the modern world ...

A huge volume of digital data has been harvested, stored and shared in the last few years - from sources such as social media, geolocation systems and aerial images from drones and satellites - giving researchers many new ways to study information and decrypt our world. In Switzerland, the Federal Statistical Office (FSO) has taken an interest in the big data revolution and the possibilities it offers to generate predictive statistics for the benefit of society.

Conventional methods such as censuses and surveys remain the benchmark for generating socio-economic indicators at the municipal, cantonal and national levels. But these methods can now be supplemented with secondary, mostly pre-existing data, from sources such as cell-phone ...

More than five years after receiving an experimental immunotherapy drug, half of a group of people at high risk of developing Type 1 diabetes remained disease-free compared with 22% of those who received a placebo, according to a new trial overseen by Yale School of Medicine researchers.

And those who developed diabetes did so on average about five years after receiving the new drug, called teplizumab, compared with 27 months for those who received the placebo.

The study, which was done in collaboration with researchers from Indiana University, was published March 3 in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

"If approved for use, this will be the first drug to delay or prevent Type 1 diabetes," ...

A series of nanoparticle-based vaccines elicits protective antibodies against various strains of the influenza virus in nonhuman primates, according to work from Nicole Darricarrère and colleagues. Although more research is needed, the vaccines mark an important step toward a universal flu vaccine for humans, which has long been a major goal for infectious disease researchers. Current seasonal flu vaccines can prevent disease but often only work for a year, after which a new vaccine must be developed. This occurs because influenza viruses evolve extremely quickly, meaning that a year-old vaccine may not prepare the immune system to recognize a new ...

Endangered Southern Resident killer whales prey on a diversity of Chinook and other salmon. The stocks come from an enormous geographic range as far north as Alaska and as far south as California's Central Valley, a new analysis shows.

The diverse salmon stocks each have their own migration patterns and timing. They combine to provide the whales with a "portfolio" of prey that supports them across the entire year. The catch is that many of the salmon stocks are at risk themselves.

"If returns to the Fraser River are in trouble, and Columbia River returns are strong, then prey availability to the whales potentially balances out ...

Scientists from the Skoltech Center for Design, Manufacturing and Materials (CDMM) and the Institute for Metals Superplasticity Problems (IMSP RAS) have studied the fatigue behavior of additive-manufactured high-entropy alloys (HEA). The research was published in the Journal of Alloys and Compounds.

Conventional 20th century materials that are extensively used in industries and mechanical engineering have reached their performance limit. Nowadays, alloying is commonly used to improve the alloys' mechanical performance and increase their operating temperature. ...

Coastal communities at the forefront of climate change reveal valuable approaches to foster adaptability and resilience, according to a worldwide analysis of small-scale fisheries by Stanford University researchers.

Globally important for both livelihood and nourishment, small-scale fisheries employ about 90 percent of the world's fishers and provide half the fish for human consumption. Large-scale shocks -- like natural disasters, weather fluctuations, oil spills and market collapse -- can spell disaster, depending on the fisheries' ability to adapt to change. In an assessment of 22 small-scale fisheries that experienced stressors, researchers revealed that diversity and flexibility are among the most important adaptive capacity factors ...