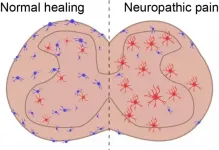

(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, NC - One of the hallmarks of chronic pain is inflammation, and scientists at the UNC School of Medicine have discovered that anti-inflammatory cells called MRC1+ macrophages are dysfunctional in an animal model of neuropathic pain. Returning these cells to their normal state could offer a route to treating debilitating pain caused by nerve damage or a malfunctioning nervous system.

The researchers, who published their work in Neuron, found that stimulating the expression of an anti-inflammatory protein called CD163 reduced signs of neuroinflammation in the spinal cord of mice with neuropathic pain.

"Macrophages are a type of immune cell that are found in the blood and in tissues throughout the body. We found a class of anti-inflammatory macrophages that normally help the body to resolve pain. But neuropathic pain appears to disable these macrophages and prevent them from doing their job," said senior author Mark Zylka, PhD, director of the UNC Neuroscience Center and Kenan Distinguished Professor of Cell Biology and Physiology. "Fortunately they don't appear to be permanently disabled, as we were able to coax them to ramp up their anti-inflammatory actions and reduce neuropathic pain. We suspect it will be possible to develop new treatments for pain by boosting the activities of these macrophages."

Roughly one-fifth of the U.S. population has chronic pain, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Often the underlying causes are elusive, and patients need pain alleviated so they can function in life. While opioids are great at treating pain in the short term, these drugs can have severe side effects when used for extended periods, such as addiction, respiratory depression, dizziness, nausea, and death due to overdose.

One reason why strong pain relievers work well but can have dramatic side effects has to do with a basic biological fact: pain involves a highly diverse set of cells and current treatments lack cell type specificity. So, any given medication may resolve adverse changes in some cells to alleviate pain, but the medication might exacerbate a particular function in other cells, leading to adverse side effects.

With an emerging technology called single-cell RNA-sequencing, scientists can now interrogate thousands of cells at once to see which cells are altered during chronic pain, and in which ways the cells change.

"Knowing which cells to target allows us to design very specific therapies. Targeted therapies in theory should have fewer adverse side-effects," said Jesse Niehaus, graduate student in the Zylka lab and first author of the Neuron paper.

To figure out which cells were changing and in what ways, Zylka's lab performed single-cell RNA-sequencing on the spinal cords of mice with neuropathic pain, a type of chronic pain caused by nerve damage. The spinal cord undergoes many long-term changes that contribute to neuropathic pain.

From those experiments, the researchers found a population of anti-inflammatory cells called MRC1+ macrophages that were dysfunctional.

"This was incredibly interesting because long-term inflammation in the spinal cord is commonly seen in animals with neuropathic pain," Niehaus said.

With the identity of the cells revealed, Zylka's lab delivered a gene therapy designed to stimulate the expression of an anti-inflammatory protein called CD163 in MRC1+ macrophages. With this approach, a single treatment reduced spinal cord inflammation and relieved pain-related behavior for up to a month.

"This discovery is quite exciting," Zylka said, "As it immediately suggests multiple distinct ways to boost the function of these macrophages. Any one of these therapeutic approaches could provide a more precise way to treat neuropathic pain."

INFORMATION:

Other authors of the Neuron paper are Jeremy Simon, PhD, research assistant professor; Bonnie Taylor-Blake, research specialist, and Lipin Loo, PhD, a former postdoc in the Zylka Lab who is now a research fellow at the University of Sidney.

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke funded this research. Sequencing was performed at the UNC High Throughput Sequencing Core. Microscopy was performed at the UNC Neuroscience Center Microscopy Core.

What The Study Did: In this study of return-to-play cardiac testing performed on 789 professional athletes with COVID-19 infection, imaging evidence of inflammatory heart disease that resulted in restriction from play was identified in five athletes (0.6%). No adverse cardiac events occurred in the athletes who underwent cardiac screening and resumed professional sports participation.

Authors: David J. Engel, M.D., of Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0565)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of ...

What The Study Did: Using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction testing, this study found that SARS-CoV-2 was present on the ocular surface in 52 of 91 patients with COVID-19 (57.1%). The virus may also be detected on ocular surfaces in patients with COVID-19 when the nasopharyngeal swab is negative.

Authors: Claudio Azzolini, M.D., of the University of Insubria in Varese, Italy, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2020.5464)

Editor's ...

What The Study Did: This study of more than 526,000 procedures across 17 institutions reports a significant decrease in the use of lasers and cryotherapy, retinal detachment repairs and other vitrectomies, beginning mid-March last year and lasting at least until May.

Authors: Mark P. Breazzano, M.D., of the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.0036)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. ...

What The Study Did: Clinical trial registrations for COVID-19 interventions that were highly publicized during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with treatments not comparably promoted were assessed in this study.

Authors: Nadir Yehya, M.D., M.S.C.E., of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, is the author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0689)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the feasibility and acceptability of using a mobile robotic system to perform health care tasks such as acquiring vital signs, obtaining nasal or oral swabs and facilitating contactless triage interviews of patients with potential COVID-19 in the emergency department.

Authors: Giovanni Traverso M.B., B.Chir., Ph.D., of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0667)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts ...

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- In the era of social distancing, using robots for some health care interactions is a promising way to reduce in-person contact between health care workers and sick patients. However, a key question that needs to be answered is how patients will react to a robot entering the exam room.

Researchers from MIT and Brigham and Women's Hospital recently set out to answer that question. In a study performed in the emergency department at Brigham and Women's, the team found that a large majority of patients reported that interacting with a health care provider via a video screen mounted on a robot was similar to an in-person interaction with a health care worker.

"We're ...

How governments and companies should listen to the people on climate change

People are more engaged in reducing carbon emissions than previously thought - and governments, scientists and companies should listen to them - according to new research from the University of East Anglia and the UK Energy Research Centre.

A new study published today in Nature Energyy investigates how invested people are in making the changes needed to reduce carbon emissions and stop climate change.

The study shows that people, their views and actions should be included more when it comes to how we transform the way we use energy, to keep global average temperatures well below 2°C as set out in the Paris COP21 climate agreement.

Lead ...

HOUSTON -- Contrary to long-held beliefs, Type I collagen produced by cancer-associated fibroblasts may not promote cancer development but instead plays a protective role in controlling pancreatic cancer progression, reports a new study from researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. This new understanding supports novel therapeutic approaches that bolster collagen rather than suppress it.

The study finds that collagen works in the tumor microenvironment to stop the production of immune signals, called chemokines, that lead to suppression of the anti-tumor immune response. When collagen is lost, chemokine levels increase, and the cancer is allowed ...

Digital solutions including remote monitoring can help chronic pain sufferers manage their pain and reduce the probability of misuse of prescription opioids.

For chronic pain sufferers an app may be just the tool they need to manage their pain. In a UHN-led study that used the app "Manage My Pain" enrolled patients saw clinically significant reductions in key areas that drive increased medical needs, potential abuse of prescription opioids and of course, pain.

Toronto (March 4, 2021) - For the first time, an app has been shown to reduce key symptoms of chronic pain. A UHN-led study evaluated the impact of Manage My Pain (MMP), a digital health solution developed ...

The body's immune response plays a crucial role in the course of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition to antibodies, the so-called T-killer cells, are also responsible for detecting viruses in the body and eliminating them. Scientists from the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine of the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Medical University of Vienna have now shown that SARS-CoV-2 can make itself unrecognizable to the immune response by T-killer cells through mutations. The findings of the research groups of Andreas Bergthaler, Judith Aberle and Johannes Huppa provide important clues for the further development of vaccines and were published in the journal Science ...