At least in some cases, the original cancer-causing mutation could have appeared as long as 40 years ago, according to a new study by researchers at Harvard Medical School and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

Reconstructing the lineage history of cancer cells in two individuals with a rare blood cancer, the team calculated when the genetic mutation that gave rise to the disease first appeared. In a 63-year-old patient, it occurred at around age 19; in a 34-year-old patient, at around age 9.

The findings, published in the March 4 issue of Cell Stem Cell, add to a growing body of evidence that cancers slowly develop over long periods of time before manifesting as a distinct disease. The results also present insights that could inform new approaches for early detection, prevention, or intervention.

"For both of these patients, it was almost like they had a childhood disease that just took decades and decades to manifest, which was extremely surprising," said co-corresponding study author Sahand Hormoz, HMS assistant professor of systems biology at Dana-Farber.

"I think our study compels us to ask, when does cancer begin, and when does being healthy stop?" Hormoz said. "It increasingly appears that it's a continuum with no clear boundary, which then raises another question: When should we be looking for cancer?"

In their study, Hormoz and colleagues focused on myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs), a rare type of blood cancer involving the aberrant overproduction of blood cells. The majority of MPNs are linked to a specific mutation in the gene JAK2. When the mutation occurs in bone marrow stem cells, the body's blood cell production factories, it can erroneously activate JAK2 and trigger overproduction.

To pinpoint the origins of an individual's cancer, the team collected bone marrow stem cells from two patients with MPN driven by the JAK2 mutation. The researchers isolated a number of stem cells that contained the mutation, as well normal stem cells, from each patient, and then sequenced the entire genome of each individual cell.

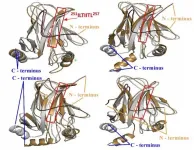

Over time and by chance, the genomes of cells randomly acquire so-called somatic mutations--nonheritable, spontaneous changes that are largely harmless. Two cells that recently divided from the same mother cell will have very similar somatic mutation fingerprints. But two distantly related cells that shared a common ancestor many generations ago will have fewer mutations in common because they had the time to accumulate mutations separately.

Cell of origin

Analyzing these fingerprints, Hormoz and colleagues created a phylogenetic tree, which maps the relationships and common ancestors between cells, for the patients' stem cells--a process similar to studies of the relationships between chimpanzees and humans, for example.

"We can reconstruct the evolutionary history of these cancer cells, going back to that cell of origin, the common ancestor in which the first mutation occurred," Hormoz said.

Combined with calculations of the rate at which mutations accumulate, the team could estimate when the JAK2 mutation first occurred. In the patient who was first diagnosed with MPN at age 63, the team found that the mutation arose around 44 years prior, at the age of 19. In the patient diagnosed at age 34, it arose at age 9.

By looking at the relationships between cells, the researchers could also estimate the number of cells that carried the mutation over time, allowing them to reconstruct the history of disease progression.

"Initially, there's one cell that has the mutation. And for the next 10 years there's only something like 100 cancer cells," Hormoz said. "But over time, the number grows exponentially and becomes thousands and thousands. We've had the notion that cancer takes a very long time to become an overt disease, but no one has shown this so explicitly until now."

The team found that the JAK2 mutation conferred a certain fitness advantage that helped cancerous cells outcompete normal bone marrow stem cells over long periods of time. The magnitude of this selective advantage is one possible explanation for some individuals' faster disease progression, such as the patient who was diagnosed with MPN at age 34.

In additional experiments, the team carried out single-cell gene expression analyses in thousands of bone marrow stem cells from seven different MPN patients. These analyses revealed that the JAK2 mutation can push stem cells to preferentially produce certain blood cell types, insights that may help scientists better understand the differences between various MPN types.

Together, the results of the study offer insights that could motivate new diagnostics, such as technologies to identify the presence of rare cancer-causing mutations currently difficult to detect, according to the authors.

"To me, the most exciting thing is thinking about at what point can we detect these cancers," Hormoz said. "If patients are walking into the clinic 40 years after their mutation first developed, could we have caught it earlier? And could we prevent the development of cancer before a patient ever knows they have it, which would be the ultimate dream?"

The researchers are now further refining their approach to studying the history of cancers, with the aim of helping clinical decision-making in the future.

While their approach is generalizable to other types of cancer, Hormoz notes that MPN is driven by a single mutation in a very slow growing type of stem cell. Other cancers may be driven by multiple mutations, or in faster-growing cell types, and further studies are needed to better understand the differences in evolutionary history between cancers.

The team's current efforts include developing early detection technologies, reconstructing the histories of greater numbers of cancer cells, and investigating why some patients' mutations never progress into full-blown cancer, but others do.

"Even if we can detect cancer-causing mutations early, the challenge is to predict which patients are at risk of developing the disease, and which are not," Hormoz said. "Looking into the past can tell us something about the future, and I think historical analyses such as the ones we conducted can give us new insights into how we could be diagnosing and intervening."

INFORMATION:

Study collaborators include scientists and physicians from Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston Children's Hospital, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the European Bioinformatics Institute. The other co-corresponding authors of the study are Ann Mullally and Isidro Cortés-Ciriano.

Additional authors include Debra Van Egeren, Javier Escabi, Maximilian Nguyen, Shichen Liu, Christopher Reilly, Sachin Patel, Baransel Kamaz, Maria Kalyva, Daniel DeAngelo, Ilene Galinsky, Martha Wadleigh, Eric Winer, Marlise Luskin, Richard Stone, Jacqueline Garcia, Gabriela Hobbs, Fernando Camargo, and Franziska Michor.

The study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants R00GM118910, R01HL158269), the Jayne Koskinas Ted Giovanis Foundation for Health and Policy, the William F. Milton Fund at Harvard University, an AACR-MPM Oncology Charitable Foundation Transformative Cancer Research grant, Gabrielle's Angel Foundation for Cancer Research, and the Claudia Adams Barr Program in Cancer Research.

DOI: 10.1016/j.stem.2021.02.001