(Press-News.org) Bioengineers at the University of California San Diego and San Diego State University have discovered a key feature that allows cancer cells to break from typical cell behavior and migrate away from the stiffer tissue in a tumor, shedding light on the process of metastasis and offering possible new targets for cancer therapies.

It has been well documented that cells typically migrate away from softer tissue to stiffer regions within the extracellular matrix-- a process called durotaxis. Metastatic cancer cells are the rare exception to this rule, moving away from the stiffer tumor tissue to softer tissue, and spreading the cancer as they migrate. What enables these cells to display this atypical behavior, called adurotaxis, and migrate away from the stiffer tumor hasn't been well understood.

Building off previous research led by bioengineers in UC San Diego Professor Adam Engler's lab, which found that weakly adherent, or less sticky, cells migrated and invaded other tissues more than strongly adherent cells, the team has now shown that the contractility of these weakly adherent cells is what enables them to move to less stiff tissue. By chemically reducing the contractility of weakly adherent cells, they become durotactic, migrating toward stiffer tissue; increasing the contractility of strongly adherent cells makes them migrate down the stiffness gradient. The researchers reported their findings on March 9 in Cell Reports.

"The main takeaway here is that the less adherent, more contractile cells are the ones that don't exhibit typical durotactic behavior," said Benjamin Yeoman, a bioengineering PhD student in the joint program at UC San Diego and SDSU, and first author of the study. "But beyond that, we see this in several different types of cancer, which opens up the possibility that maybe there's this commonality between different types of carcinomas that could potentially be a target for a more universal treatment."

To find out what enables this atypical behavior, Yeoman first used computational models developed in bioengineer Parag Katira's lab in the SDSU Department of Mechanical Engineering, to try and pinpoint what was different about the cells that were able to move against the stiffness gradient. The models showed that changing a cell's contractile force could modulate the cell's adhesion strength in an environment of a certain stiffness, which would change their ability to be durotactic. To confirm the computational results, Yeoman used a microfluidic flow chamber device designed for previous research on cell adherence in Engler's lab, to experiment with the contractility of real cancer cells from breast cancer, prostate cancer and lung cancer cell lines.

"It worked perfectly," said Katira, co-corresponding author of the paper. "It was really an ideal collaboration, where you have experimental results that show something is different; then you have a computational model that predicts it and explains why something is happening; and then you go back and do experiments to actually test if that's going on. All of these blocks fell into place to bring this interesting result."

The parallel plate flow chamber device used to test the computational theory was designed by engineers in Engler's lab studying the effect of adherence on cell metastasis and cancer recurrence, and first described in Cancer Research in February 2020. Using this patent pending device, the researchers now isolated cells based on adhesion strength, and seeded them onto photopatterned hydrogels with alternating soft and stiff profiles. The researchers used time-lapse video microscopy to watch how the cells moved, and found that strongly adherent cells would durotax, moving to stiffer sections, while weakly adherent cells would migrate to softer tissue.

After investigating several potential mechanisms within the cell enabling this behavior, the team focused on contractility as a key marker of its ability to adurotax. By modulating the number of active myosin motors within the cell-- a marker of contractile ability-- they were able to get previously durotactic cells to migrate away from stiffer tissue, and previously adurotactic, weakly adherent cells to migrate up the stiffness gradient.

The researchers hope that this work, and the further development of the microfluidic cell sorting device, will enable better assessments of disease prognosis in the future. Their ultimate aim is to be able to use the parallel plate flow chamber as a way to measure the metastatic potential of a patient's cells, and use that as a predictor for cancer recurrence to drive more effective treatments and outcomes.

"Understanding the mechanisms that govern invasion of many different tumor types enables us to better use this device to sort and count cells with weak adhesion and their percentage in a tumor, which may correlate with poor patient outcomes," said Adam Engler, professor of bioengineering at UC San Diego and co-corresponding author of the paper.

The researchers cautioned that this discovery doesn't preclude other mechanisms from playing a role in the metastasis of cells. It does, however, highlight the important role that adherence and contractility do play, which needs to be studied further.

"The point is not to say that nothing else can drive cells away from a tumor," said Katira. "There could be other drivers for metastasis, but this is clearly an important mechanism, and the fact that cells can do this across lung, breast and pancreatic cancer cells tells us this is generalizable."

Going forward, the engineers plan to study other parameters that may contribute to adurotaxis; investigate the effect of different types of tumor environments on a cell's ability to adurotax; and move from the individual cell scale to the population scale, to see how adhesion and contractility function and can be modulated when there is a mixed population of cells with unique mechanical properties.

INFORMATION:

This project was funded by grants from the National Science Foundation, National Institutes of Health and the Army Research Office.

WASHINGTON, March 9, 2021 -- Spinal cord injuries can be life-changing and alter many important neurological functions. Unfortunately, clinicians have relatively few tools to help patients regain lost functions.

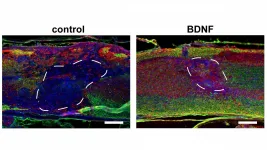

In APL Bioengineering, by AIP Publishing, researchers from UCLA have developed materials that can interface with an injured spinal cord and provide a scaffolding to facilitate healing. To do this, scaffolding materials need to mimic the natural spinal cord tissue, so they can be readily populated by native cells in the spinal cord, essentially filling in gaps left by injury.

"In this study, we demonstrate that incorporating a regular network of pores throughout these materials, where pores are sized similarly to normal cells, increases infiltration of cells from spinal cord tissue ...

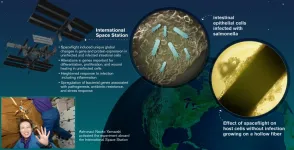

Astronauts face many challenges to their health, due to the exceptional conditions of spaceflight. Among these are a variety of infectious microbes that can attack their suppressed immune systems.

Now, in the first study of its kind, Cheryl Nickerson, lead author Jennifer Barrila and their colleagues describe the infection of human cells by the intestinal pathogen Salmonella Typhimurium during spaceflight. They show how the microgravity environment of spaceflight changes the molecular profile of human intestinal cells and how these expression patterns are further changed in response to infection. In another first, the researchers were also able to detect ...

PORTOLA VALLEY, CA, March 9, 2021 -- Bay Area Lyme Foundation, a leading sponsor of Lyme disease research in the U.S., today announced the publication of new data finding that five herbal medicines had potent activity compared to commonly-used antibiotics in test tubes against Babesia duncani, a malaria-like parasite found on the West Coast of the U.S. that causes the disease babesiosis. Published in the journal Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, the laboratory study was funded in part by the Bay Area Lyme Foundation. Collaborating researchers were from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, California Center for Functional Medicine, and FOCUS Health Group, Naturopathic.

"This research is particularly important ...

A study published in the journal eLife made all the possible mutations in the amyloid beta peptide and tested how they influence its aggregation into plaques, a pathological hallmark of Alzheimer's disease.

The comprehensive mutation map, which is the first of its kind, has the potential to help clinical geneticists predict whether the mutations found in amyloid beta can make an individual more prone to developing Alzheimer's disease later in life.

The complete atlas of mutations will also help researchers better understand the biological mechanisms that control the onset of the disease.

"The genetic sequencing of individuals is increasingly common. As a result, we are ...

While it's an unfair reality that women who develop gestational diabetes are ten times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes later in life, only a third of these women realise that they're at high risk, according to new research by the University of South Australia.

Conducted in partnership with the University College Dublin, the research examined the views of 429 Australian women with a history of gestational diabetes to establish their perceived risks of developing type 2 diabetes, potential barriers to losing weight, and useful strategies for supporting a healthy weight.

Lead researcher, UniSA's Kristy ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Producing high-value pharmaceutical proteins in plants--sometimes called "molecular pharming"--offers advantages over some other manufacturing methods, notably the low cost and ease of scaling up production to meet demand. But expressing large quantities of "foreign" proteins in plants can also sometimes lead to problems, such as dehydration and premature cell death in the leaves.

Now a team led by Professor Kenji Miura of the University of Tsukuba has discovered that spraying leaves with high concentrations of the antioxidant ascorbic acid (vitamin C) can increase protein production three-fold or even more. They recently published their findings in Plant Physiology.

The team worked with a close relative of tobacco, ...

The fossil in question is that of an oviraptorosaur, a group of bird-like theropod dinosaurs that thrived during the Cretaceous Period, the third and final time period of the Mesozoic Era (commonly known as the 'Age of Dinosaurs') that extended from 145 to 66 million years ago. The new specimen was recovered from uppermost Cretaceous-aged rocks, some 70 million years old, in Ganzhou City in southern China's Jiangxi Province.

"Dinosaurs preserved on their nests are rare, and so are fossil embryos. This is the first time a non-avian dinosaur has been found, sitting on a nest of eggs that preserve embryos, in a single ...

For the first time, two researchers--one from the University of Copenhagen and the other from Columbia University--have accurately dated the arrival of the first herbivorous dinosaurs in East Greenland. Their results demonstrate that it took the dinosaurs 15 million years to migrate from the southern hemisphere, as a consequence of being slowed down by extreme climatic conditions. Their long walk was only possible because as CO2 levels dropped suddenly, the Earth's climate became less extreme.

A snail could have crawled its way faster. 10,000 km over 15 million years--that's how long it took the first herbivorous dinosaurs to make their way from Brazil and Argentina all the way to East Greenland. This, according to a new study by Professor ...

Chili peppers (Capsicum spp.) are an important spice and vegetable that supports food culture around the world, whose intensity of its pungent taste is determined by the content of capsicumoids. However, the content of capsicumoids varies depending on the variety and is known to fluctuate greatly depending on the cultivation environment. This can be a big problem in the production, processing and distribution of peppers where sweet varieties can be spicy and highly spicy varieties are just only mildly spicy. It is thought that changes in the expression of multiple genes involved in capsaicinoid biosynthesis are involved in such changes in pungent taste ...

When something bad happens to a child, the public and policy response is swift and forceful.

How could this have happened?

What went wrong?

What do we do to make sure it never happens again?

When a family becomes erroneously or unnecessarily enmeshed in the child welfare system, that burden is largely invisible - a burden borne mostly by the family itself.

In both situations, the fault for the systemic failure is often placed on the caseworker - overburdened, under-resourced, and forced to make quick and critical judgments about the risk ...