(Press-News.org) Cooperation is generally a good thing -- working together to reach a goal.

But in the case of cancer, it can be detrimental. University of Cincinnati researchers have discovered that cooperation between two key genes drive cancer growth, spread and treatment resistance in one particularly aggressive type of breast cancer.

The good news is, though, with this knowledge, they can continue to aim their targeted treatments at these genes, singularly and together, to stop breast cancer in its tracks.

This study is published in the March 9 online edition of the journal Cell Reports.

"According to the American Cancer Society's estimate, over 280,000 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in women in 2021," explains Xiaoting Zhang, PhD, professor and Thomas Boat Endowed Chair in UC's Department of Cancer Biology, director of the Breast Cancer Research Program and member of the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center, who led this research. "Like many other cancers, breast cancer cells are fueled by mutations and overproduction of 'driver' genes, which lead the process of cancer development."

He says one of these genes, called HER2 (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2), accounts for about 20% of all human breast cancer cases, and while there are some therapies to target it, unwanted side effects and treatment resistance often occur in patients, causing relapse.

"There are about a dozen additional genes, including one called MED1, located within the same chromosomal region where HER2 and other genes are multiplied in breast cancer, but it's not known whether any of these genes are simply 'passenger' genes, and let HER2 to do the driving, or actually collaborate with the gene to play significant roles in the development, spread and treatment resistance of this type of breast cancer."

To investigate this, the team created an animal model with an overproduction of both genes, HER2 and MED1, in the mammary gland.

This helped researchers discover the key role MED1 played in helping HER2 promote breast tumor growth, spread and treatment resistance. They found that the genes could in fact work with each other to further speed up their production and activities, which in turn promotes rapid cell multiplication, movement and invasion to spread cancer and cause treatment resistance.

Zhang adds that previous research has shown that MED1 has a role in treatment resistance in another type of breast cancer, ER+ (estrogen receptor positive). This UC study established MED1 as a key driver in the development and treatment resistance of two major kinds of breast cancer.

"Our findings suggest that targeting MED1, alone and in combination with current therapies, could be an effective treatment strategy for nearly 90% of breast cancer patients in clinics and combat treatment resistance to two widely used breast cancer therapies," Zhang says.

Zhang and his team have already developed a treatment targeting MED1 specifically in tumors, using RNA nanotechnology similar to that used for the COVID-19 vaccines, and have observed positive outcomes. This technology is currently patent pending.

Creating foundations for future research, careers

Yongguang Yang, PhD, first author on this study and a research associate in Zhang's lab, says the work he's done on studying the roles of these genes in cancer and treatment resistance is eye-opening and takes a true "teamwork" approach.

"Working together as a team is very important in this process, as collaborations with the basic cancer biology researchers, clinical teams and physicians ensure our access to their unique insights and firsthand clinical experience, data and samples," he says. "These findings are exciting and relate very closely to how this cancer impacts people. This new animal model we created has a wide range of future applications and will allow us to continue to study basic molecular mechanisms of this type of breast cancer to find and test new therapies."

"It was very exciting to be able to not only conduct my graduate studies on something so innovative and impactful as identifying new ways that breast cancers function, but also to develop potential applications for the future of cancer treatment," adds co-author, Marissa Leonard, PhD, a recent doctoral graduate of the cancer and cell biology program at UC. "One or the other is often seen in research labs, but doing both is something I would consider a rare opportunity."

"The scientific experience, knowledge and writing skills I gained from Dr. Zhang's lab and our graduate program at UC have greatly broadened my horizons and allowed me to familiarize myself with a wide range of scientific concepts," says Leonard, who is now a medical writer. "These broad, laboratory-based skill sets bode well for many different career paths, too, whether that includes continued research, medical writing, regulatory science, patent law, teaching or others."

INFORMATION:

Authors and collaborators of this study also include UC breast oncologists Elyse Lower, MD, and Mahmoud Charif, MD; pathologist Jiang Wang, MD, PhD; cancer biology researcher Jun-Lin Guan, PhD, and his lab members Syn Yeo, PhD, and Mingang Hao, PhD; Zhenhua Luo, PhD, of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center; and Gregory Bick, PhD, and Chunmiao Cai, PhD, from Zhang's laboratory.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA197865 and R01CA229869), Ohio Cancer Research Seed Grant, University of Cincinnati Cancer Center and Ride Cincinnati Awards. Researchers cite no conflict of interest.

Some of Princeton's leading cancer researchers were startled to discover that what they thought was a straightforward investigation into how cancer spreads through the body -- metastasis -- turned up evidence of liquid-liquid phase separations: the new field of biology research that investigates how liquid blobs of living materials merge into each other, similar to the movements seen in a lava lamp or in liquid mercury.

"We believe this is the first time that phase separation has been implicated in cancer metastasis," said Yibin Kang, the Warner-Lambert/Parke-Davis Professor of Molecular Biology. He is the ...

Broad political, economic, and social factors influence disciplinary punishment. In particular, over the last half century, such considerations have shaped jurisdictions' use of the death penalty, which has declined considerably since the 1990s. A new study examined the factors associated with use of the death penalty at the county level to provide a fuller picture of what issues influence court outcomes. The study concludes that partisan politics, religious fundamentalism, and economic threat influenced local decisions about the death penalty. The study also found that the size of the African American population, which ...

CHAPEL HILL, NC -- In a viewpoint perspective published in JAMA on March 9, 2021, a University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center researcher and two other experts endorsed the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services' (CMS) requirement for a patient and their doctor to engage in a shared discussion of benefits and harms before proceeding with a low-dose spiral computed tomography (LDCT) scan as a method for preventing lung cancer death. An accompanying evidence report detailed the benefits and harms from screening, suggesting that shared decision-making between a patient ...

URBANA, Ill. - If you haven't been the parent or caregiver of an infant in recent years, you'd be forgiven for missing the human milk oligosaccharide trend in infant formulas. These complex carbohydrate supplements mimic human breast milk and act like prebiotics, boosting beneficial microbes in babies' guts.

Milk oligosaccharides aren't just for humans, though; all mammals make them. And new University of Illinois research suggests milk oligosaccharides may be beneficial for cats and dogs when added to pet diets.

But before testing the compounds, scientists had to find them.

"When we first looked into this, there had only been one study on milk oligosaccharides in dogs, and none in domestic cats. The closest were really small studies on a single lion and a single ...

In a new study in PNAS, an international team of researchers including scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology has shown that Arabidopsis thaliana plants produce beta-cyclocitral when attacked by herbivores and that this volatile signal inhibits the methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway. The MEP pathway is instrumental in plant growth processes, such as the production of pigments for photosynthesis. In addition to down-regulating the MEP pathway, beta-cyclocitral also increases plant defenses against herbivores. Since the MEP pathway is only found in plants and microorganisms, but not animals, knowledge of a signal molecule like beta-cyclocitral opens up new possibilities for the development ...

Brazilian researchers who study a native venomous fish have confirmed a route to drug development for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases such as multiple sclerosis and asthma.

The venomous toadfish Thalassophryne nattereri contains a peptide (TnP) with anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic potential. Confirmation of this potential has now come via the zebrafish Danio rerio, a popular aquarium species native to South Asia that shares 70% of its genome with humans and is widely used as a model for in vivo trials in drug development.

The researchers tested TnP in D. rerio to measure its toxicity. In a little over a year, their research showed that the peptide is safe. It did not cause cardiac dysfunction or neurological problems in the toxicity tests ...

Health care systems could save lives and minimize losses by optimizing resource allocation and implementing mitigation strategies, according to two new studies. Colorado State University researchers explored how our health care systems might perform under multiple disasters and multiple waves of COVID-19, and how we can keep them functioning when we need them most.

In the first study, published in Nature Communications, Civil and Environmental Engineering Ph.D. student Emad Hassan and Associate Professor Hussam Mahmoud investigated the compound effects of pandemics and natural disasters on health care systems. They combined wildfire ...

DALLAS (March 9, 2021) - Better brain health and performance for humankind is one step closer to reality with the successful trial of the groundbreaking BrainHealth Project. A cross-disciplinary team with the Center for BrainHealth® at The University of Texas at Dallas unveiled an easy-to-use online platform that delivers a novel, science-backed approach to measuring, improving and tracking one's own brain fitness.

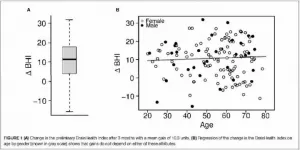

A key innovation of the Project centers on the BrainHealth Index™ (BHI), which is based on a multidimensional definition of brain health and its upward potential. The BHI is a composite derived from a series of best-in-class assessments that explore ...

Farmers in the Midwest may be able to bypass the warming climate not by getting more water for their crops, but instead by adapting to climate change through soil management says a new study from Michigan State University.

"The Midwest supplies 30% of the world's corn and soybeans," said Bruno Basso, an ecosystems scientist and MSU Foundation Professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences within the College of Natural Science. "These crops are sensitive to temperature and water changes."

Previous studies have suggested that by 2050, the Midwest will need about 35% more water to sustain its current levels of corn and soybean yields. But research done by Basso and colleagues found that the data does not support this idea. The Midwest is in a unique location that ...

If past natural disasters have taught us anything about their effects on pregnant women and developing babies, it is to pay close attention, for the added stress will surely have an impact on them. Amanda Venta, associate professor of psychology at the University of Houston, is sounding that alarm as it relates to the COVID-19 pandemic in a newly released study published in Child Psychiatry & Human Development.

"There is strong evidence to suggest that the coronavirus pandemic will affect mothers and infants through immune pathways that, in previous research, have been shown to link stress and social isolation during the pre- and post-natal periods with deficits in maternal mental health and infant well-being and development across developmental stages," reports Venta.

Research ...