But this particle just so happened to smash into an electron deep inside the South Pole's glacial ice. The collision created a new particle, known as the W- boson. That boson quickly decayed, creating a shower of secondary particles.

The whole thing played out in front of the watchful detectors of a massive telescope buried in the Antarctic ice, the IceCube Neutrino Observatory. This enabled IceCube to make the first ever detection of a Glashow resonance event, a phenomenon predicted 60 years ago by Nobel laureate physicist Sheldon Glashow.

This detection provides the latest confirmation of the Standard Model, the name of the particle physics theory explaining the universe's fundamental forces and particles.

"Finding it wasn't necessarily a surprise, but that doesn't mean I wasn't very happy to see it," said Claudio Kopper, an associate professor in Michigan State University's Department of Physics and Astronomy in the College of Natural Science. Kopper and his departmental colleague, assistant professor Nathan Whitehorn, lead IceCube's Diffuse and Atmospheric Flux Working Group behind the discovery.

The international IceCube Collaboration published this result online on March 11 in the journal Nature.

"Even three years ago, I didn't think IceCube would be able to make this measurement, or at least as well as we did," Whitehorn said.

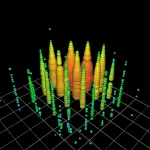

A 3-D plot with columns of green, blue, yellow and orange spheres and other round shapes give a visual representation of the Glashow resonance event detection.

This detection further demonstrates the ability of IceCube, which observes nearly massless particles called neutrinos using thousands of sensors embedded in the Antarctic ice, to do fundamental physics.

Although the Spartans lead the working group, they emphasized that this discovery was a team effort, powered by the paper's three lead analysts: Lu Lu, an assistant professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison; Tianlu Yuan, an assistant scientist at the Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center, or WIPAC; and Christian Haack, a postdoc at the Technical University of Munich.

"We lead weekly meetings, we talk about how the work is done, we ask hard questions," said Kopper. "But without the people doing the actual analysis, we wouldn't have anything."

"Our job is to be the doubters-in-chief," Whitehorn said. "The lead authors did a great job convincing everyone that this event was a Glashow resonance."

The particle physics community has been anticipating such a detection, but Glashow resonance events are extremely rare by nature and technologically challenging to detect.

"When Glashow was a postdoc at Niels Bohr, he could never have imagined that his unconventional proposal for producing the W- boson would be realized by an antineutrino from a faraway galaxy crashing into Antarctic ice," said Francis Halzen, professor of physics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the headquarters of IceCube maintenance and operations, and principal investigator of IceCube.

A Glashow resonance event requires an electron antineutrino with a cosmic amount of energy -- at least 6.3 peta-electronvolts, or PeV. For comparison, that's about 1,000 times more energy than that of the most energetic particles produced by the Earth's most powerful particle accelerators.

Since IceCube started fully operating in 2011, it has detected hundreds of high-energy neutrinos from space. Yet the neutrino in December 2016 was only the third with an energy higher than 5 PeV.

And simply having a high-energy neutrino is not sufficient to detect a Glashow resonance event. The neutrino then has to interact with matter, which is not a guarantee. But IceCube encompasses quite a bit of matter in the form of Antarctic ice.

The IceCube Laboratory, lighted red against the night sky, is small in this landscape photograph of the South Pole white tundra, which also captures yellow stars and light green auroras.

The observatory's detector array has been built into the ice, spanning nearly 250 acres with sensors reaching up to about a mile deep. All told, IceCube boasts a cubic kilometer of coverage, watching over a billion metric tons of extremely clear ice.

That's what it takes to detect neutrinos, along with a team of scientists who have the skill and determination to spot rare events.

IceCube's more than 5,000 detectors take in a tremendous firehose of light, Whitehorn said. Detecting the Glashow resonance meant researchers had to pick out a handful of telltale photons, individual particles of light, from that firehose spray.

"This is some of the most impressive technical work I've ever seen," Whitehorn said, calling the team unstoppable over the years-long effort to confirm this was a Glashow resonance event.

Making the work even more impressive was the fact that the lead authors -- Lu, Yuan and Haack -- were in three countries on three different continents during the analysis. Lu was a postdoc at Chiba University in Japan, Yuan was at WIPAC in the U.S. and Haack was a doctoral student at Rheinisch-Westfälische Technische Hochschule Aachen University in Germany.

"It was amazing to me just seeing that that is possible," Kopper said.

But this is very much in keeping with the ethos of IceCube, an observatory built on international collaboration. IceCube is operated by a group of scientists, engineers and staff from 53 institutions in 12 countries, together known as the IceCube Collaboration. The project's headquarters is WIPAC, a research center of UW-Madison in the United States.

To confirm the detection and usher in a new chapter of neutrino astronomy, the IceCube Collaboration is working to detect more Glashow resonances. And they need IceCube-Gen2, a proposed expansion of the IceCube detector, to make it happen.

"We already know that the astrophysical spectrum does not end at 6 PeV," Lu said. "The key is to detect more Glashow resonance events and to identify the sources that accelerate those antineutrinos. IceCube-Gen2 will be key to making such measurements in a statistically significant way."

Glashow himself echoed that sentiment about validation. "To be absolutely sure, we should see another such event at the very same energy as the one that was seen," said Glashow, now an emeritus professor of physics at Boston University. "So far there's one, and someday there will be more."

INFORMATION:

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory is funded primarily by the National Science Foundation and is operated by a team headquartered at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. IceCube's research efforts, including critical contributions to the detector operation, are funded by agencies in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, Republic of Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. IceCube construction was also funded with significant contributions from the National Fund for Scientific Research -- the FNRS and FWO -- in Belgium; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research and the German Research Foundation in Germany; the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat, and the Swedish Research Council in Sweden; and the Department of Energy and the University of Wisconsin-Madison Research Fund in the U.S.

(Note for media: Please include a link to the original paper in online coverage: https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03256-1)