(Press-News.org) New bioarchaeological research shows malaria has threatened human communities for more than 7000 years, earlier than when the onset of farming was thought to have sparked its devastating arrival.

Lead author Dr Melandri Vlok from the Department of Anatomy, University of Otago, says this ground-breaking research, published today in Scientific Reports, changes the entire understanding of the relationship humans have had with malaria, still one of the deadliest diseases in the world.

"Until now we've believed malaria became a global threat to humans when we turned to farming, but our research shows in at least Southeast Asia this disease was a threat to human groups well before that.

"This research providing a new cornerstone of malaria's evolution with humans is a great achievement by the entire team," Dr Vlok says.

Still a serious health issue, as recently as 2019 the World Health Organization reported an estimated 229 million cases of malaria around the world, with 67 per cent of malaria deaths in children under the age of 5 years.

While malaria is invisible in the archaeological record, the disease has changed the evolutionary history of human groups causing consequences visible in prehistoric skeletons. Certain genetic mutations can lead to the inheritance of Thalassemia, a devasting genetic disease that in its milder form provides some protection against malaria.

Deep in humanity's past, the genes for malaria became more common in Southeast Asia and the Pacific where it remains a threat, but up until now the origin of malaria has not been pinpointed. This research has identified thalassemia in an ancient hunter-gatherer archaeological site from Vietnam dated to approximately 7000 years ago, thousands of years before the transition to farming in the region.

In some parts of the world, slashing and burning in agricultural practice would have created pools of stagnant water attracting mosquitos carrying malaria, but in Southeast Asia these mosquitos are common forest dwellers exposing humans to the disease long before agriculture was adopted.

The study Forager and farmer evolutionary adaptations to malaria evidenced by 7000 years of thalassemia in Southeast Asia is a result of combined efforts from years of investigation by a team of researchers led by Professor Marc Oxenham (currently at the University of Aberdeen) and including researchers from University of Otago, the Australian National University (ANU), James Cook University, Vietnam Institute of Archaeology and Sapporo Medical University.

The research is the first of its kind to use microscopic techniques to investigate changes in bone tissue to identify thalassemia. In 2015, Professor Hallie Buckley from the University of Otago noticed changes in the bone of hunter-gatherers that made her suspicious that thalassemia might be the cause, but the bones were too poorly preserved to be certain. Professor Buckley called in microscopic bone expert Dr Justyna Miszkiewicz of ANU to investigate. Under the microscope, the ancient samples from Vietnam showed evidence for abnormal porosity mirroring modern-day bone loss complications in thalassemic patients.

At the same time, Dr Vlok, completing her doctoral research in Vietnam, found changes in the bones excavated in a 4000-year-old agricultural site in the same region as the 7000-year-old hunter-gatherer site. The combined research suggests a long history of evolutionary changes to malaria in Southeast Asia which continues today.

"A lot of pieces came together, then there was a startling moment of realisation that malaria was present and problematic for these people all those years ago, and a lot earlier than we've known about until now," Dr Vlok adds.

INFORMATION:

When people think of sea level rise, they usually think of coastal erosion. However, recent computer modeling studies indicate that coastal wastewater infrastructure, which includes sewer lines and cesspools, is likely to flood with groundwater as sea-level rises.

A new study, published by University of Hawai'i (UH) at Mānoa earth scientists, is the first to provide direct evidence that tidally-driven groundwater inundation of wastewater infrastructure is occurring today in urban Honolulu, Hawai'i. The study shows that higher ocean water levels ...

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) have revolutionized the displays industry. LEDs use electric current to produce visible light without the excess heat found in traditional light bulbs, a glow called electroluminescence. This breakthrough led to the eye-popping, high-definition viewing experience we've come to expect from our screens. Now, a group of physicists and chemists have developed a new type of LED that utilizes spintronics without needing a magnetic field, magnetic materials or cryogenic temperatures; a "quantum leap" that could take displays to the next level.

"The companies that make LEDs or TV and computer displays don't want to deal with magnetic fields and magnetic materials. It's heavy ...

TOKYO - Toshiba Corporation (TOKYO: 6502), the industry leader in solutions for large-scale optimization problems, today announced a scale-out technology that minimizes hardware limitations, an evolution of its optimization computer, the Simulation Bifurcation Machine (SBM), that supports continued increases in computing speed and scale. Toshiba expects the new SBM to be a game changer for real-world problems that require large-scale, high-speed and low-latency, such as simultaneous financial transactions involving large numbers of stock, and complex control of multiple robots. The research results were published in Nature Electronics*1 on March 1.

Speed and scale are keys to success in industrial sectors ...

Waste cooking oil, sulfur and wool offcuts have been put to good use by green chemists at Flinders University to produce a sustainable new kind of housing insulation material.

The latest environmentally friendly building product from experts at the Flinders Chalker Lab and colleagues at Deakin and Liverpool University, has been described in a new paper published in Chemistry Europe ahead of Global Recycling Day (18 March 2021)

The insulating composite was made from the sustainable building blocks of wool fires, sulfur, and canola oil to produce a promising new model for next-generation insulation - not only capitalising on wool's natural low flammability but also to make significant energy savings for property owners and tenants.

The new composite is one of several exciting ...

Magnetic reconnection refers to the reconfiguration of magnetic field geometry. It plays an elemental role in the rapid release of magnetic energy and its conversion to other forms of energy in magnetized plasma systems throughout the universe.

Researchers led by Dr. LI Leping from the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC) analyzed the evolution of magnetic reconnection and its nearby filament. The result suggested that reconnection is significantly accelerated by the propagating disturbance caused by the adjacent filament eruption.

The study was published in The Astrophysical Journal on Feb. 25.

The New Vacuum Solar Telescope (NVST) is a ...

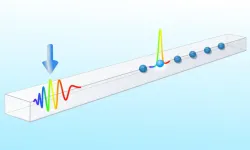

In order to exploit the properties of quantum physics technologically, quantum objects and their interaction must be precisely controlled. In many cases, this is done using light. Researchers at the University of Innsbruck and the Institute of Quantum Optics and Quantum Information (IQOQI) of the Austrian Academy of Sciences have now developed a method to individually address quantum emitters using tailored light pulses. "Not only is it important to individually control and read the state of the emitters," says Oriol Romero-Isart, "but also to do so while leaving the system as undisturbed as possible." Together with Juan Jose? Garci?a-Ripoll (IQOQI visiting fellow) from the Instituto de Fi?sica Fundamental in Madrid, Romero-Isart's research group has ...

CLEMSON, South Carolina -- By using laser spectroscopy in a photophysics experiment, Clemson University researchers have broken new ground that could result in faster and cheaper energy to power electronics.

This novel approach, using solution-processed perovskite, is intended to revolutionize a variety of everyday objects such as solar cells, LEDs, photodetectors for smart phones and computer chips. Solution-processed perovskite are the next generation materials for solar cell panels on rooftops, X-ray detectors for medical diagnosis, and LEDs for daily-life lighting.

The research team included ...

A multiyear workplace health promotion program can slow down the increase in health risks for working-age people. A study by the Faculty of Sport and Health Sciences at the University of Jyväskylä followed what kind of changes happened among participants during an eight-year workplace health promotion program in smoking, minor exercise, high blood pressure, musculoskeletal disorders, and overweight. The results of the study were encouraging for health promotion.

According to earlier studies, a high number of health risks are connected to an increase in occupational health care costs, lower productivity at work, and the growing number of sickness ...

CLEVELAND--Scientists at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine have determined the structure of protein "fibrils" linked to Lou Gehrig's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders--findings that provide clues to how toxic proteins clump and spread between nerve cells in the brain.

Their results may also lead to developing drugs to treat diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

"These devastating brain disorders that affect tens of thousands of Americans?are on the rise worldwide, and there are no effective treatments to ...

Researchers at Tufts University School of Engineering have created light-activated composite devices able to execute precise, visible movements and form complex three-dimensional shapes without the need for wires or other actuating materials or energy sources. The design combines programmable photonic crystals with an elastomeric composite that can be engineered at the macro and nano scale to respond to illumination.

The research provides new avenues for the development of smart light-driven systems such as high-efficiency, self-aligning solar cells that automatically follow the sun's direction and angle of light, light-actuated microfluidic valves or soft robots that move with light on demand. A "photonic sunflower," whose petals curl ...