New proteins 'out of nothing'

International team of researchers investigates how evolution forms the structure and function of a newly emerged protein in flies

2021-03-12

(Press-News.org) Proteins are the key component in all modern forms of life. Haemoglobin, for example, transports the oxygen in our blood; photosynthesis proteins in the leaves of plants convert sunlight into energy; and fungal enzymes help us to brew beer and bake bread. Researchers have long been examining the question of how proteins mutate or come into existence in the course of millennia. That completely new proteins - and, with them, new properties - can emerge practically out of nothing, was inconceivable for decades, in line with what the Greek philosopher Parmenides said: "Nothing can emerge from nothing" (ex nihilo nihil fit). Working with colleagues from the USA and Australia, researchers from the University of Münster (Germany) have now reconstructed how evolution forms the structure and function of a newly emerged protein in flies. This protein is essential for male fertility. The results have been published in the journal "Nature Communications".

The background:

It had been assumed up to now that new proteins emerge from already existing proteins - by a duplication of the underlying genes and by a series of small mutations in one or both gene copies. In the past ten years, however, a new understanding of protein evolution has come about: proteins can also develop from so-called non-coding DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) - in other words, from that part of the genetic material which does not normally produce proteins - and can subsequently develop into functional cell components. This is surprising for several reasons: for many years, it had been assumed that, in order to be functional, proteins had to take on a highly developed geometrical form (a "3D structure"). It had further been assumed that such a form could not develop from a gene emerging at random, but would require a complex combination of amino-acids enabling this protein to exist in its functional form.

Despite decades of trying, researchers worldwide have not yet succeeded in constructing proteins with the desired 3D structures and functions, which means that the "code" for the formation of a functioning protein is essentially unknown. While this task remains a puzzle for scientists, nature has proven to be more adept at the formation of new proteins. A team of researchers headed by Prof. Erich Bornberg-Bauer, from the Institute of Evolution and Biodiversity at the University of Münster, discovered, by comparing the newly analysed genomes in numerous organisms, that species not only differ through duplicated protein-coding genes adapted in the course of evolution. In addition, proteins are constantly being formed de novo ("anew") - i.e. without any related precursor protein going through a selection process.

The vast majority of these de novo proteins are useless, or even slightly deleterious, as they can interfere with existing proteins in the cell. Such new proteins are quickly lost again after several generations, as organisms carrying the new gene encoding the protein have impaired survival or reproduction. However, a select few de novo proteins prove to have beneficial functions. These proteins integrate into the molecular components of cells and eventually, after millions of years of minor modifications, become indispensable. There are some important questions which many reearchers wonder about in this context: How do such novel proteins look like upon birth? How do they change, and which functions do they assume as the "new kids on the block"? Spearheaded by Prof. Bornberg-Bauer's group in Münster, an international team of researchers has answered this question in much detail for "Goddard", a fruit fly protein that is essential for male fertility.

Methodology

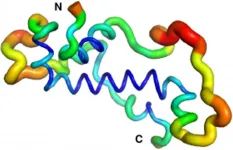

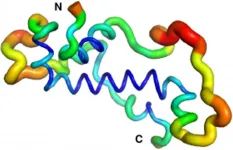

The research proceeded on three related fronts across three continents. At the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts, USA, Dr. Prajal Patel and Prof. Geoff Findlay used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to show that male flies that do not produce Goddard are sterile, but otherwise healthy. Meanwhile, Dr. Andreas Lange and PhD student Brennen Heames of Prof. Bornberg-Bauer's group used biochemical techniques to predict the shape of the novel protein in present-day flies. They then used evolutionary methods to reconstruct the likely structure of Goddard ~50 million years ago when the protein first arose. What they found was quite a surprise: "The ancestral Goddard protein looked already very much like the ones which exist in fly species today" Erich Bornberg-Bauer explains. "Right from the beginning, Goddard contained some structural elements, so called alpha-helices, which are believed to be essential for most proteins." To confirm these findings, the scene shifted to the Australian National University in Canberra, where Dr. Adam Damry and Prof. Colin Jackson used intensive, computational simulations to verify the predicted shape of the Goddard protein. They validated the structural analysis of Dr. Lange and showed that Goddard, in spite of its young age, is already quite stable - though not quite as stable as most fly proteins that are believed to have existed for longer, perhaps hundreds of millions of years.

The results match up with several other current studies, which have shown that the genomic elements from which protein-coding genes emerge are activated frequently - tens of thousands of times in each individual. These fragments are then "sorted" through the process of evolutionary selection. The ones which are useless or harmful - the vast majority - are quickly discarded. But those which are neutral, or are slightly beneficial, can be optimized over millions of years and changed into something useful.

INFORMATION:

Funding

The research undertaken received funding from the European Grant EsCat within the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Framework Programme No. 722610 (Münster), from the ARC Centres of Excellence in Peptide and Protein Science and Synthetic Biology (Australia), and from an NSF CAREER Grant #1652013 (USA).

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-12

The Cabeza de los Gatos waste rock pile, left from mining activities in the town of Tharsis (Huelva), underwent a rehabilitation process consisting of remodelling the slope of the pile, applying liming materials and then a layer of soil. Finally, trees and shrubs typical of the area were planted and a hydroseeding with a mixture of shrub and herbaceous seeds was applied. Twelve years later, a study led by researchers from IRNAS-CSIC, in collaboration with Sabina Rossini Oliva, a researcher from the University of Seville and the Environment and Water Agency of Andalusia (AMAYA), has proven the effectiveness of this sort of rehabilitation.

"The results obtained show that the steps taken were successful. Now, ...

2021-03-12

People with high levels of emotional intelligence are less likely to be susceptible to 'fake news', according to research at the University of Strathclyde.

The study invited participants to read a series of news items on social media and to ascertain whether they were real or fictitious, briefly describing the reasons for their answers. They were also asked to complete a test to determine their levels of emotional intelligence (EQ or emotional quotient) and were asked a number of questions when considering the veracity of each news item.

Researchers found that those who identified the types of news correctly were most likely to score highly in the EQ tests. There was a similar correlation between correct identification and educational attainment.

The ...

2021-03-12

In asthma, the airways become hyperresponsive. Researchers from Uppsala University have found a new mechanism that contributes to, and explains, airway hyperresponsiveness. The results are published in the scientific journal Allergy.

Some 10 per cent of Sweden's population suffer from asthma. In asthmatics, the airways are hyperresponsive (overreactive) to various types of stimuli, such as cold air, physical exertion and chemicals. The airways become constricted, making breathing difficult.

To diagnose asthma, a "methacholine test" is commonly used to determine whether a person is showing signs of airway hyperresponsiveness. Methacholine binds to what are known as muscarinic receptors in the smooth muscle cells lining the inside ...

2021-03-12

The researchers say this is a big step in tackling smouldering peat fires, which are the largest fires on Earth. They ignite very easily, are notoriously difficult to put out, and release up to 100 times more carbon into the atmosphere than flaming fires, contributing to climate change.

The fires, known as 'zombie fires' for their ability to hide and smoulder underground and then reanimate as new flames days or weeks after the wildfire had been extinguished, are prevalent in regions like Southeast Asia, North America, and Siberia.

They are driven by the burning of soils rich in organic content like peat, which is a large natural reservoir of carbon. Worldwide, peat fires account for millions of tonnes of carbon released into the atmosphere each year.

Firefighters currently use millions ...

2021-03-12

A new model of aging takes into account not only genetics and environmental exposures but also the tiny changes that randomly arise at the cellular level.

University Professor Caleb Finch introduced the "Tripartite Phenotype of Aging" as a new conceptual model that addresses why lifespan varies so much, even among human identical twins who share the same genes. Only about 10 to 35 percent of longevity can be traced to genes inherited from our parents, Finch mentioned.

Finch authored the paper introducing the model with one of his former graduate students, Amin Haghani, who received his PhD in the Biology of Aging from the USC ...

2021-03-12

Researchers at Lund University in Sweden can now show that a new examination method identifies high-risk plaques in the blood vessels surrounding the heart, that cannot be seen solely with traditional angiograms. This type of plaque, rich in fat, could potentially cause recurring heart attacks in patients with heart disease. The study is published in the The Lancet.

"We have been working on this study for ten years. This creates a unique opportunity to treat plaques before they cause a heart attack", says David Erlinge, professor of cardiology at Lund University and Consultant in ...

2021-03-12

During 1995-2015, fullerene derivatives had been the dominating electron acceptors in organic solar cells (OSCs) owing to their performance superior to other acceptors. However, the drawbacks of fullerenes, such as weak visible absorption, limited tunability of electronic properties and morphological instability, restrict further development of OSCs toward higher efficiencies and practical applications. Therefore, the development of new acceptors beyond fullerenes is urgent in the field of OSCs.

Professor Zhan Xiaowei from the College of Engineering at Peking University is one of the pioneers engaging in development of nonfullerene acceptors in the world. ...

2021-03-12

University of Otago researchers have discovered one of the reasons why more than 50 per cent of people with type 2 diabetes die from heart disease.

And perhaps more significantly, they have found how to treat it.

Associate Professor Rajesh Katare, of the Department of Physiology, says it has been known that stem cells in the heart of diabetic patients are impaired. While stem cell therapy has proved effective in treating heart disease, it is not the case in diabetic hearts.

It has not been known why; until now.

It comes down to tiny molecules called microRNA which control gene expression.

"Based on the results of laboratory testing, ...

2021-03-12

New bioarchaeological research shows malaria has threatened human communities for more than 7000 years, earlier than when the onset of farming was thought to have sparked its devastating arrival.

Lead author Dr Melandri Vlok from the Department of Anatomy, University of Otago, says this ground-breaking research, published today in Scientific Reports, changes the entire understanding of the relationship humans have had with malaria, still one of the deadliest diseases in the world.

"Until now we've believed malaria became a global threat to humans when we turned to farming, but our research shows in at least Southeast Asia this disease was a threat to human groups well before that.

"This research providing a new cornerstone of malaria's evolution with humans is a great achievement ...

2021-03-12

When people think of sea level rise, they usually think of coastal erosion. However, recent computer modeling studies indicate that coastal wastewater infrastructure, which includes sewer lines and cesspools, is likely to flood with groundwater as sea-level rises.

A new study, published by University of Hawai'i (UH) at Mānoa earth scientists, is the first to provide direct evidence that tidally-driven groundwater inundation of wastewater infrastructure is occurring today in urban Honolulu, Hawai'i. The study shows that higher ocean water levels ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] New proteins 'out of nothing'

International team of researchers investigates how evolution forms the structure and function of a newly emerged protein in flies