(Press-News.org) We all have a clear picture in mind when we think of metals: We think of solid, unbreakable objects that conduct electricity and exhibit a typical metallic sheen. The behaviour of classical metals, for example their electrical conductivity, can be explained with well-known, well-tested physical theories.

But there are also more exotic metallic compounds that pose riddles: Some alloys are hard and brittle, special metal oxides can be transparent. There are even materials right at the border between metal and insulator: tiny changes in chemical composition turn the metal into an insulator - or vice versa. In such materials, metallic states with extremely poor electrical conductivity occur; these are referred to as "bad metals". Until now, it seemed that these "bad metals" simply could not be explained with conventional theories. New measurements now show that these metals are not that "bad" after all. Upon closer inspection, their behaviour fits in perfectly with what we already knew about metals.

Small change, big difference

Prof. Andrej Pustogow and his research group at the Institute for Solid State Physics at TU Wien (Vienna) are conducting research on special metallic materials - small crystals that have been specially grown in the laboratory. "These crystals can take on the properties of a metal, but if you vary the composition just a little bit, we are suddenly dealing with an insulator that no longer conducts electricity and is transparent like glass at certain frequencies," says Pustogow.

Right at this transition, one encounters an unusual phenomenon: the electrical resistance of the metal becomes extremely large - larger, in fact, than should be possible at all according to conventional theories. "Electrical resistance has to do with the electrons being scattered at each other or at the atoms of the material", explains Andrej Pustogow. According to this view, the greatest possible electrical resistance should occur if the electron is scattered at every single atom on its way through the material - after all, there is nothing between an atom and its neighbour that could throw the electron off its path. But this rule does not seem to apply to so-called "bad metals": They show a much higher resistance than this model would allow.

It all depends on the frequency

The key to solving this puzzle is that the material properties are frequency-dependent. "If you just measure the electrical resistance by applying a DC voltage, you only get a single number - the resistance at zero frequency," says Andrej Pustogow. "We, on the other hand, made optical measurements using light waves with different frequencies."

This showed that the "bad metals" are not so "bad" after all: At low frequencies they hardly conduct any current, but at higher frequencies they behave as one would expect from metals. The research team considers tiny amounts of impurities or defects in the material, that can no longer be adequately shielded by a metal at the boundary to an insulator, as a possible cause. These defects can cause some areas of the crystal to no longer conduct electricity because there the electrons remain localized in a certain place instead of moving through the material. If a DC voltage is applied to the material so that the electrons can move from one side of the crystal to the other, then virtually every electron will eventually hit such an insulating region and current can hardly flow.

At high AC frequency, on the other hand, every electron moves back and forth continuously - it does not cover a long distance in the crystal because it keeps changing direction. This means that in this case many electrons do not even come into contact with one of the insulating regions in the crystal.

Hope for important further steps

"Our results show that optical spectroscopy is a very important tool for answering fundamental questions in solid-state physics," says Andrej Pustogow. "Many observations for which it was previously believed that exotic, novel models had to be developed could very well be explained by existing theories if they were adequately extended. Our measurement method shows where the additions are necessary." Already in earlier studies, Prof. Pustogow and his international colleagues gained important insight into the boundary region between metal and insulator using spectroscopic methods, thus establishing a fundament for theory.

The metallic behaviour of materials subject to strong correlations between the electrons is also particularly relevant for so-called "unconventional superconductivity" - a phenomenon that was discovered half a century ago but is still not fully understood.

INFORMATION:

Contact

Ass. Prof. Dr. Andrej Pustogow

Institute for Solid State Physics

TU Wien

+43 1 58801 13128

pustogow@ifp.tuwien.ac.at

http://www.ifp.tuwien.ac.at/forschung/pustogow-research/home

Cryoprotectants are used to protect biological material during frozen storage

They have to be removed when defrosting, and how much to use and how exactly they inhibit ice recrystallisation is poorly understood

The polymer poly(vinyl)alcohol (PVA) is arguably the most potent ice recrystallisation inhibitor and researchers from the University of Warwick have unravelled how exactly it works.

This newly acquired knowledge base provides novel guidelines to design the next generation of cryoprotectants

When biological material (cells, blood, tissues) is frozen, cryoprotectants are used to prevent the damage associated with the formation of ...

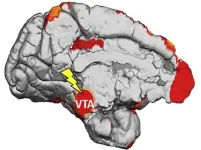

Researchers uncovered for the first time what happens in animals' brains when they learn from subconscious, visual stimuli. In time, this knowledge can lead to new treatments for a number of conditions. The study, a collaboration between KU Leuven, Massachusetts General Hospital, and Harvard was published in Neuron.

An experienced birdwatcher recognises many more details in a bird's plumage than the ordinary person. Thanks to extensive training, he or she can identify specific features in the plumage. This learning process is not only dependent on conscious processes. Previous research has shown that when people are rewarded during the presentation of visual stimuli that are not consciously perceivable, ...

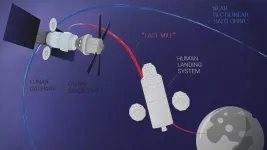

Researchers from Skoltech and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have analyzed several dozen options to pick the best one in terms of performance and costs for the 'last mile' of a future mission to the Moon - actually delivering astronauts to the lunar surface and back up to the safety of the orbiting lunar station. The paper was published in the journal Acta Astronautica.

Ever since December 1972, when the crew of Apollo 17 left the lunar surface, humans have been eager to return to the Moon. In 2017, the US government launched the Artemis program, which intends ...

An RCSI study conducted in Beaumont Hospital in Dublin has found that surgery, rather than antibiotics-only, should remain as the mainstay of treatment for acute uncomplicated appendicitis.

Published in the Annals of Surgery and led by researchers from the RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, the study entitled the COMMA trial (Conservative versus Open Management of Acute uncomplicated Appendicitis) examined the efficacy and quality of life associated with antibiotic-only treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis versus surgical intervention. The results revealed that antibiotic-only treatment resulted in high recurrence rates and an inferior quality ...

Drugs such as beta-adrenergic antagonists (beta blockers) have been linked to a range of adverse effects, including depression. But how reliable are these data, and which psychiatric side effects might indeed be caused by these drugs? These questions have been addressed by a team of researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, whose comprehensive meta-analysis has been published in Hypertension*. While treatment with beta blockers was not found to be associated with an increased incidence of depression, some studies recorded higher levels of sleep disturbance.

Beta-adrenergic ...

During the past decade the European People's Party in the European Parliament was criticized for its unwillingness to vote for measures that would sanction the Hungarian Fidesz government, which is accused of breaching key democratic principles.

Researchers have said the EPP protected Fidesz in order to safeguard Hungarian votes in its ranks and protect their own interests, but this support had weakened by 2019, when Fidesz was suspended from the EPP.

Researchers analysed the votes of EPP MEPs for 24 resolutions covering the protection of EU fundamental values ...

(Boston)-- Warning signs for Alzheimer's disease (AD) can begin in the brain years before the first symptoms appear. Spotting these clues may allow for lifestyle changes that could possibly delay the disease's destruction of the brain.

"Improving the diagnostic accuracy of Alzheimer's disease is an important clinical goal. If we are able to increase the diagnostic accuracy of the models in ways that can leverage existing data such as MRI scans, then that can be hugely beneficial," explained corresponding author Vijaya B. Kolachalama, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at Boston University School ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - An analysis of historic and projected simulations from 19 global climate models shows that, because of climate change, the temperature in the Antarctic peninsula will increase by 0.5 to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2044.

The projections also showed that precipitation - a threat to ice if it manifests as rain - will likely increase on the peninsula by about 5% to 10% over that same time period.

The estimates were published recently in the journal Climate Dynamics.

"We are concerned about these findings. We've been seeing overall quite big changes on the peninsula, generally getting warmer and ice shelves and glaciers discharging into the ocean," said David Bromwich, a leading author of the study and a research professor at The Ohio State University ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Proposals to create a national gun registry have long been met with fierce opposition from gun rights advocates. While proponents say a registry would help in tracking guns used in crimes, opponents worry that it would compromise privacy and could be used by the federal government to confiscate firearms. Now, a team of Brown University computer scientists has devised a way of implementing a registry that may allay some of those concerns.

They propose a database that uses advanced encryption to protect privacy. The encryption scheme allows the database to be searched without being decrypted, which means people querying the database see only the records they're looking for and nothing else. Meanwhile, the system places control of data ...

Lemurs can use their sense of smell to locate fruit hidden more than 50 feet away in the forest--but only when the wind blows the fruit's aroma toward them, according to a study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

"This is the first time research has demonstrated that primates can track a distant smell carried by the wind," said anthropologist Elena Cunningham, a clinical associate professor of molecular pathobiology at NYU College of Dentistry and the study's lead author.

Many animals use their sense of smell to locate food. However, less is known about whether primates can smell food that is far away, or if they instead rely on visual cues or memory to find their next meal.

Because many primates--including ring-tailed lemurs, ...