It is well known that airborne particulate matter can pose a danger to human health. The particles, with a maximum diameter of ten micrometres, can penetrate deep into lung tissue and settle there. They contain reactive oxygen species (ROS), also called oxygen radicals, which can damage the cells of the lungs. The more particles there are floating in the air, the higher the risk. The particles get into the air from natural sources such as forests or volcanoes. But human activities, for example in factories and traffic, multiply the amount so that concentrations reach a critical level. The potential of particulate matter to bring oxygen radicals into the lungs, or to generate them there, has already been investigated for various sources. Now the PSI researchers have gained important new insights.

From previous research it is known that some ROS are formed in the human body when particulates dissolve in the surface fluid of the respiratory tract. Particulate matter usually contains chemical components, for instance metals such as copper and iron, as well as certain organic compounds. These exchange oxygen atoms with other molecules, and highly reactive compounds are created, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl (HO), and hydroperoxyl (HO2), which cause so-called oxidative stress. For example, they attack the unsaturated fatty acids in the body, which then can no longer serve as building blocks for the cells. Physicians attribute pneumonia, asthma, and various other respiratory diseases to such processes. Even cancer could be triggered, since the ROS can also damage the genetic material DNA.

New insights thanks to a unique combination of devices

It has been known for some time that certain reactive oxygen species are already present in particulates in the atmosphere, and that they enter our body as so-called exogenous ROS by way of the air we breathe, without having to form there first. As it now turns out, scientists had not yet looked closely enough: "Previous studies have analysed the particulate matter with mass spectrometers to see what it consists of," explains Peter Aaron Alpert, first author of the new PSI study. "But that does not give you any information about the structure of the individual particles and what is going on inside them."

Alpert, in contrast, used the possibilities PSI offers to take a more precise look: "With the brilliant X-ray light from the Swiss Light Source SLS, we were able not only to view such particles individually with a resolution of less than one micrometre, but even to look into particles while reactions were taking place inside them." To do this, he also used a new type of cell developed at PSI, in which a wide variety of atmospheric environmental conditions can be simulated. It can precisely regulate temperature, humidity, and gas exposure, and has an ultraviolet LED light source that stands in for solar radiation. "In combination with high-resolution X-ray microscopy, this cell exists just one place in the world," says Alpert. The study therefore would only have been possible at PSI. He worked closely with the head of the Surface Chemistry Research Group at PSI, Markus Ammann. He also received support from researchers working with atmospheric chemists Ulrich Krieger and Thomas Peter at ETH Zurich, where additional experiments were carried out with suspended particles, as well as experts working with Hartmut Hermann from the Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research in Leipzig.

How dangerous compounds form

The researchers examined particles containing organic components and iron. The iron comes from natural sources such as desert dust and volcanic ash, but it is also contained in emissions from industry and traffic. The organic components likewise come from both natural and anthropogenic sources. In the atmosphere, these components combine to form iron complexes, which then react to so-called radicals when exposed to sunlight. These in turn bind all available oxygen and thus produce the ROS.

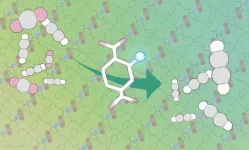

Normally, on a humid day, a large proportion of these ROS would diffuse from the particles into the air. In that case it no longer poses additional danger if we inhale the particles, which contain fewer ROS. On a dry day, however, these radicals accumulate inside the particles and consume all available oxygen there within seconds. And this is due to viscosity: Particulate matter can be solid like stone or liquid like water - but depending on the temperature and humidity, it can also be semi-fluid like syrup, dried chewing gum, or Swiss herbal throat drops. "This state of the particle, we found, ensures that radicals remain trapped in the particle," says Alpert. And no additional oxygen can get in from the outside.

It is especially alarming that the highest concentrations of ROS and radicals form through the interaction of iron and organic compounds under everyday weather conditions: with an average under 60 percent and temperatures around 20 degrees C., also typical conditions for indoor rooms. "It used to be thought that ROS only form in the air - if at all - when the fine dust particles contain comparatively rare compounds such as quinones," Alpert says. These are oxidised phenols that occur, for instance, in the pigments of plants and fungi. It has recently become clear that there are many other ROS sources in particulate matter. "As we have now determined, these known radical sources can be significantly reinforced under completely normal everyday conditions." Around every twentieth particle is organic and contains iron.

But that's not all: "The same photochemical reactions likely takes place also in other fine dust particles," says research group leader Markus Ammann. "We even suspect that almost all suspended particles in the air form additional radicals in this way," Alpert adds. "If this is confirmed in further studies, we urgently need to adapt our models and critical values with regard to air quality. We may have found an additional factor here to help explain why so many people develop respiratory diseases or cancer without any specific cause."

At least the ROS have one positive side - especially during the Covid-19 pandemic - as the study also suggests: They also attack bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens that are present in aerosols and render them harmless. This connection might explain why the SARS-CoV-2 virus has the shortest survival time in air at room temperature and medium humidity.

INFORMATION:

Text: Jan Berndorff

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2100 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 400 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research).

Contact

Prof. Dr. Markus Ammann

Head of the Surface Chemistry Research Group

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232

Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 40 49;

e-mail: markus.ammann@psi.ch

[German, English]

Dr. Peter Aaron Alpert

Surface Chemistry Research Group

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232

Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 39 34;

e-mail: peter.alpert@psi.ch

[English]

Original publication

Photolytic Radical Persistence due to Anoxia in Viscous Aerosol Particles

Peter A. Alpert, Jing Dou, Pablo Corral Arroyo, Frederic Schneider, Jacinta Xto, Beiping Luo, Thomas Peter, Thomas Huthwelker, Camelia N. Borca, Katja D. Henzler, Thomas Schaefer, Hartmut Herrmann, Jörg Raabe, Benjamin Watts, Ulrich K. Krieger, Markus Ammann

Nature Communications, 19.03.2021

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-21913-x