(Press-News.org) Repeatedly getting angry, hitting, shaking or yelling at children is linked with smaller brain structures in adolescence, according to a new study published in Development and Psychology. It was conducted by Sabrina Suffren, PhD, at Université de Montréal and the CHU Sainte?Justine Research Centre in partnership with researchers from Stanford University.

The harsh parenting practices covered by the study are common and even considered socially acceptable by most people in Canada and around the world.

"The implications go beyond changes in the brain. I think what's important is for parents and society to understand that the frequent use of harsh parenting practices can harm a child's development," said Suffren, the study's lead author. "We're talking about their social and emotional development, as well as their brain development."

Emotions and brain anatomy

Serious child abuse (such as sexual, physical and emotional abuse), neglect and even institutionalization have been linked to anxiety and depression later in life.

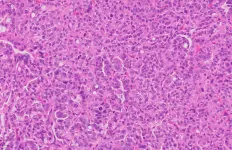

Previous studies have already shown that children who have experienced severe abuse have smaller prefrontal cortexes and amygdala, two structures that play a key role in emotional regulation and the emergence of anxiety and depression.

In this study, researchers observed that the same brain regions were smaller in adolescents who had repeatedly been subjected to harsh parenting practices in childhood, even though the children did not experience more serious acts of abuse.

"These findings are both significant and new. It's the first time that harsh parenting practices that fall short of serious abuse have been linked to decreased brain structure size, similar to what we see in victims of serious acts of abuse," said Suffren, who completed the work as part of her doctoral thesis at UdeM's Department of Psychology, under the supervision of Professors Françoise Maheu and Franco Lepore.

She added that a study published in 2019 "showed that harsh parenting practices could cause changes in brain function among children, but now we know that they also affect the very structure of children's brains."

Children monitored since birth at CHU Sainte-Justine

One of this study's strengths is that it used data from children who had been monitored since birth at CHU Saint-Justine in the early 2000s by Université de Montréal's Research Unit on Children's Psychosocial Maladjustment (GRIP) and the Quebec Statistical Institute. The monitoring was organized and carried out by GRIP members Dr. Jean Séguin, Dr. Michel Boivin and Dr. Richard Tremblay.

As part of this monitoring, parenting practices and child anxiety levels were evaluated annually while the children were between the ages of 2 and 9. This data was then used to divide the children into groups based on their exposure (low or high) to persistently harsh parenting practices.

"Keep in mind that these children were constantly subjected to harsh parenting practices between the ages of 2 and 9. This means that differences in their brains are linked to repetitive exposure to harsh parenting practices during childhood," said Suffren who worked with her colleagues to assess the children's anxiety levels and perform anatomical MRIs on them between the ages of 12 and 16.

This study is the first to try to identify the links between harsh parenting practices, children's anxiety and the anatomy of their brains.

INFORMATION:

About the study

"Prefrontal cortex and amygdala anatomy in youth with persistent levels of harsh parenting practices and subclinical anxiety symptoms over time during childhood," by Sabrina Suffren et al, was published by Development and Psychology on March 22,

This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services, the Fonds de recherche du Québec ? Société et culture, Canada's Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the CHU Sainte-Justine Research Centre, the Foundation of Stars, and Université de Montréal and Université Laval.

Cancers are not only made of tumor cells. In fact, as they grow, they develop an entire cellular ecosystem within and around them. This "tumor microenvironment" is made up of multiple cell types, including cells of the immune system, like T lymphocytes and neutrophils.

The tumor microenvironment has predictably drawn a lot of interest from cancer researchers, who are constantly searching for potential therapeutic targets. When it comes to the immune cells, most research focuses on T lymphocytes, which have become primary targets of cancer immunotherapy ...

Wikipedia page views could be used to monitor global awareness of biodiversity, proposes a research team from UCL, ZSL, and the RSPB.

Using their new metric, the research team found that awareness of biodiversity is marginally increasing, but the rate of change varies greatly between different groups of animals, as they report in a paper included in an upcoming special section of Conversation Biology.

Lead author, PhD student Joe Millard (UCL Centre for Biodiversity & Environment Research, UCL Biosciences and Institute of Zoology, ZSL) said: "As extinctions and biodiversity losses ramp up worldwide, largely due to climate change and other human actions, it's vital that ...

A study by the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund shows that gorilla families come together to support young gorillas that lose their mothers.

The findings, published in the journal eLife, use the Fossey Fund's more than 50-year dataset to discover how maternal loss influences young gorillas' social relationships, survival and future reproduction. The study shows when young mountain gorillas lose their mothers, the rest of the group helps buffer the loss by strengthening their relationships with the orphans.

"Mothers are incredibly important for survival early in life--this is something that is shared across all mammals," said lead author Dr. Robin Morrison. "But in social mammals, like ourselves, mothers often continue to provide vital support up to adulthood and even beyond."

"In ...

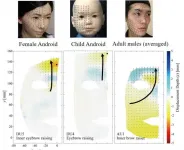

Osaka, Japan - Researchers from the Graduate School of Engineering and Symbiotic Intelligent Systems Research Center at Osaka University used motion capture cameras to compare the expressions of android and human faces. They found that the mechanical facial movements of the robots, especially in the upper regions, did not fully reproduce the curved flow lines seen in the faces of actual people. This research may lead to more lifelike and expressive artificial faces.

The field of robotics has advanced a great deal over the past decades. However, while current androids can appear very humanlike at first, their active facial expressions may still be unnatural and slightly unsettling to us. The exact reasons ...

Although cancers that occur in the gallbladder or bile ducts are rare, their rates are increasing. A recent study provides details on the burden of gallbladder and biliary tract cancer (GBTC) across 195 countries and territories from 1990 to 2017. The findings are published early online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society.

Determining GBTC estimates and trends in different global regions can help to guide research priorities and policies for prevention and treatment. With this in mind, a team of scientists examined publicly available information ...

Patient care by a single primary care physician is associated with many health benefits, including increased treatment adherence and decreased hospital admissions and mortality risk. But can the relationship built between doctor and patient also lead to unnecessary care?

A new University of Florida study finds that male patients who have a single general physician were more likely to receive a prostate cancer screening test during a period when the test was not recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force. The study, which appears in END ...

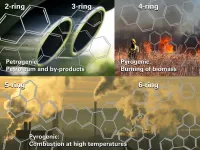

When power stations burn coal, a class of compounds called Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons, or PAHs, form part of the resulting air pollution. Researchers have found that PAHs toxins degrade in sunlight into 'children' compounds and by-products.

Some 'children' compounds can be more toxic than the 'parent' PAHs. Rivers and dams affected by PAHs are likely contaminated by a much larger number of toxins than are emitted by major polluters, researchers show in Chemosphere.

A coal-fired power station and a cigarette have more in common than one might think. So do the exhaust pipes from cars and burning crop residues. The same is true for an aeroplane passing high over a wildfire ...

Human actions are threatening the resilience and stability of Earth's biosphere - the wafer-thin veil around Earth where life thrives. This has profound implications for the development of civilizations, say an international group of researchers in a report published for the first Nobel Prize Summit, a digital gathering to be held in April to discuss the state of the planet in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

"Humanity is now the dominant force of change on planet Earth," according to the analysis published in Ambio, a journal of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

"The risks we are taking are astounding," says co-author Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and co-author of the analysis. "We are at the dawn of what must be a transformative ...

Study taken throughout the pandemic shows those who feel government should be less controlling believe COVID-19 poses less risk, which in turn was associated with the adoption of fewer protective behaviours

"A fearful population is not necessarily desirable... people may be underestimating or overestimating the actual risk at different times."

People's politics and values are exerting a bigger influence on how much of a threat they feel from COVID-19 compared to objective indicators such as the number of confirmed cases.

That's the finding of a new University of Cambridge survey which measured how attitudes to the coronavirus have varied over the course of 10 months of the pandemic for more ...

Hearing loss and other auditory problems are strongly associated with Covid-19 according to a systematic review of research evidence led by University of Manchester and NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) scientists.

Professor Kevin Munro and PhD researcher Ibrahim Almufarrij found 56 studies that identified an association between COVID-19 and auditory and vestibular problems.

They pooled data from 24 of the studies to estimate that the prevalence of hearing loss was 7.6%, tinnitus was 14.8% and vertigo was 7.2%.

They publish their findings in the International Journal of Audiology.

However, the team - who followed up their review carried out a year ago - ...