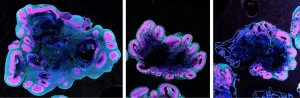

(Press-News.org) HOUSTON ? Overcoming previous technical challenges with single-cell DNA (scDNA) sequencing, a group led by researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center has developed a novel method for scDNA sequencing at single-molecule resolution. This technique revealed for the first time that triple-negative breast cancers undergo continued genetic copy number changes after an initial burst of chromosome instability.

The findings, published today in Nature, offer an accurate and efficient new approach for sequencing hundreds of individual cancer cells while also providing novel insights into cancer evolution. These insights may explain why treatments are not always effective and why researchers are not able to generate homogenous cell cultures in the laboratory.

"This represents significant progress from our first methods in single-cell DNA sequencing, with significantly increased throughput, accuracy and ease of use," said senior author Nicholas Navin, Ph.D., associate professor of Genetics and Bioinformatics & Computational Biology. "We are now able to resolve very small differences in copy number within the population of tumor cells in a way that wasn't possible previously."

The new technique, called Acoustic Cell Tagmentation (ACT), begins with fluorescent-activated cell sorting to isolate single nuclei from thousands of cells. A three-step chemistry process then cuts the DNA from each cell into precise fragments, adds universal adaptors and incorporates barcodes for next-generation sequencing.

The chemistry is performed with acoustic liquid transfer technology, which uses sound waves to transfer minute volumes of liquid rapidly and efficiently. Whereas early scDNA sequencing approaches required three days from start to finish, the new approach can be completed in just three hours, Navin explained.

With this improved method for sequencing DNA from a limited number of cells, the researchers sought to answer a standing question about cancer evolution. Navin's team previously established that triple-negative breast cancers experience punctuated evolution, acquiring copy number changes in an initial burst of chromosomal instability, but it was unknown if the cancer cells continued to accumulate changes after that event.

Led by graduate student Darlan Conterno Minussi, Navin's team worked with the laboratory of Franziska Michor, Ph.D., at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, to perform copy number analysis on 16,178 single cells from eight triple-negative breast cancers and four cell lines using the ACT technique.

"We discovered that punctuated evolution in these cells is followed by transient instability," Navin said. "After the initial event, there is a period of time with copy number changes accumulating at high rates that eventually slow to a basal rate."

The understanding that triple-negative breast cancers continue to evolve over time may explain why treatments are not always effective - a small portion of the cancer cells may have acquired a mutation that conveys resistance to a given therapy. Going forward, the researchers would like to determine if the number of genetic changes a tumor undergoes is predictive of clinical outcomes.

The findings also have implications for preclinical research, as the researchers confirmed that triple-negative breast cancer cell lines also continue to accumulate changes when cultured in the laboratory. Importantly, the researchers showed that commonly used laboratory cell culture procedures are not able to generate homogenous populations of tumor cells, since they quickly re-diversify their genomes.

The research team continues to build upon this work by investigating additional cancer types, seeking to understand if this model of cancer evolution may be broadly applicable beyond triple-negative breast cancers.

INFORMATION:

A complete list of collaborating authors and their disclosures can be found with the full paper here. This work was supported by the American Cancer Society (129098-RSG-16-092-01-TBG), the National Institutes of Health and National Cancer Institute (R01CA240526, R01CA236864, CA016672, CA016672), the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Single Cell Genomics Core Facilities Grant (RP180684), the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Martin and Rose Wachtel Cancer Research Award, the Andrew Sabin Family Fellowship, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Physical Sciences-Oncology Center and the Center for Cancer Evolution, the Francis Crick Institute, Cancer Research UK (FC001202), the UK Medical Research Council (FC001202), the Wellcome Trust (FC001202), the Winton Charitable Foundation, and the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds.

- 30 -

Joint press release by the German Cancer Research Center, University Medicine Mannheim, Heidelberg University Hospital, and the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) Heidelberg

Tumor vaccines can help the body fight cancer. Mutations in the tumor genome often lead to protein changes that are typical of cancer. A vaccine can alert the patients' immune system to these mutated proteins. For the first time, physicians and cancer researchers from Heidelberg and Mannheim have now carried out a clinical trial to test a mutation-specific vaccine against malignant brain tumors. The vaccine proved to be safe and triggered the desired immune response in the tumor tissue, as the team now reports in the journal Nature.

Diffuse ...

Researchers have developed experimental flu shots that protect animals from a wide variety of seasonal and pandemic influenza strains. The vaccine product is currently being advanced toward clinical testing. If proven safe and effective, these next-generation influenza vaccines may replace current seasonal options by providing protection against many more strains that current vaccines do not adequately cover.

A study detailing how the new flu vaccines were designed and how they protect mice, ferrets, and nonhuman primates appears in the March 24 edition of the journal Nature. This work was led by researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine and the Vaccine

Research Center part of the National Institute of Allergy ...

Many children of low-income families across the country do not have access to quality health care. Lack of health care can have a domino effect, affecting educational outcomes in the classroom.

School-based telehealth could offer a sustainable and effective solution, according to a new report in the Journal for Nurse Practitioners by Kathryn King Cristaldi, M.D., the medical director of the school-based telehealth program, and Kelli Garber, the lead advanced practice provider and clinical integration specialist for the program.

The program through the MUSC Health Center for Telehealth has effectively served over 70 schools across the state of South Carolina. Evaluating a child at school via telehealth ...

Probiotics -- those bacteria that are good for your digestive tract -- are short-lived, rarely taking residence or colonizing the gut. But a new study from researchers at the University of California, Davis, finds that in breast milk-fed babies given the probiotic B. infantis, the probiotic will persist in the baby's gut for up to one year and play a valuable role in a healthy digestive system. The study was published in the journal Pediatric Research.

"The same group had shown in a previous study that giving breast milk-fed babies B. infantis had beneficial effects that lasted up to 30 days after supplementation, but this is the first study to show persistent colonization up to 1 year of age," said lead author Jennifer Smilowitz with the UC Davis Department ...

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), often called 'fatty liver hepatitis', can lead to serious liver damage and liver cancer. A team of researchers at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) has discovered that this condition is caused by cells that attack healthy tissue - a phenomenon known as auto-aggression. Their results may help in the development of new therapies to avoid the consequences of NASH.

Fatty liver disease (NASH) is often associated with obesity. However, our understanding of the causes has been very limited. A team working with ...

Rich false memories of autobiographical events can be planted - and then reversed, a new paper has found.

The study highlights - for the first time - techniques that can correct false recollections without damaging true memories. It is published by researchers from the University of Portsmouth, UK, and the Universities of Hagen and Mainz, Germany.

There is plenty of psychological research which shows that memories are often reconstructed and therefore fallible and malleable. However, this is the first time research has shown that false memories of autobiographical events can be undone.

Studying how memories are created, identified ...

Infants prefer baby talk in any language, but particularly when it's in a language they're hearing at home.

A unique study of hundreds of babies involving 17 labs on four continents showed that all babies respond more to infant-directed speech -- baby talk -- than they do to adult-directed speech. It also revealed that babies as young as six months can pick up on differences in language around them.

"We were able to compare babies from bilingual backgrounds to babies from monolingual backgrounds, and what seemed to matter the most was the match between the language they ...

A new study is the first to identify how human brains grow much larger, with three times as many neurons, compared with chimpanzee and gorilla brains. The study, led by researchers at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK, identified a key molecular switch that can make ape brain organoids grow more like human organoids, and vice versa.

The study, published in the journal END ...

Scientists have genetically engineered immune cells, called myeloid cells, to precisely deliver an anticancer signal to organs where cancer may spread. In a study of mice, treatment with the engineered cells shrank tumors and prevented the cancer from spreading to other parts of the body. The study, led by scientists at the National Cancer Institute's (NCI) Center for Cancer Research, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), was published March 24, 2021, in Cell.

"This is a novel approach to immunotherapy that appears to have promise as a potential treatment for metastatic cancer," said the study's leader, Rosandra Kaplan, M.D., of NCI's Center for Cancer Research.

Metastatic cancer--cancer that has spread from its original location to other parts of the body--is notoriously ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the association between a recent diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or dementia and the risk of attempting suicide among older adults.

Authors: Amy L Byers, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0150)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding and support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial ...