(Press-News.org) STANFORD, Calif. — More than 2,000 genetic regions involved in early human development have been identified by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine. The regions, called enhancers, are responsible for triggering the expression of distant genes when embryonic stem cells begin to divide to form the many tissues of a growing embryo.

"This is going to be an enormous resource for researchers interested in tracking cells involved in early human development," said Joanna Wysocka, PhD, assistant professor of developmental biology and of chemical and systems biology. "It will be very interesting to learn how these enhancers affect gene expression in each cell type."

Wysocka is the senior author of the research, which will be published online Dec. 15 in Nature. Postdoctoral scholar Alvaro Rada-Iglesias, PhD, is the first author of the study.

The researchers also learned something interesting about human embryonic stem cells: They're not too shabby at planning ahead. The cells prepare for the demands of future embryonic development by priming a subset of enhancers for activation with proteins and chemical tags. These "poised" enhancers are simultaneously kept in check by other modifications that keep them inactive. When the modifications (also known as epigenetic changes) are removed, the enhancers can quickly trigger the expression of genes needed to toggle from a mere stem cell to a developing embryo.

The identification of the previously unknown enhancers, and the discovery of how they're kept quiet until needed, represent a moment of research serendipity. Wysocka and Rada-Iglesias didn't start out trying to identify enhancers involved in development. Instead, they were looking for regions that activated genes involved in the maintenance of the embryonic stem cell state.

"We are interested in understanding how genomic information is integrated with epigenetic changes to produce cell-type-specific regulation — in this case in the embryonic stem cells," said Wysocka. "Often this regulation is accomplished via gene activation mediated by a distant enhancer."

But enhancers can be difficult to identify because they trigger the activation of genes tens to hundreds of kilobases away; it's rarely clear if and where enhancers of that gene might lie without conducting laborious genetic studies. Recent studies identifying specific protein and DNA modifications associated with active enhancers are making the process easier, though.

Rada-Iglesias mixed antibodies that specifically recognize epigenetic changes associated with active enhancers with extracts from human embryonic stem cells. He then used a technique called chromatin immunoprecipitation to remove the antibodies from the solution and catalogued the snippets of DNA that were included in the antibody complexes.

As expected, he found about 5,000 candidate active enhancers, which he termed class-1 elements. But 2,200 additional regions were more perplexing. These had two types of modifications — both activating and inactivating. Some of these dually tagged DNAs, he noticed, were near genes known to be involved in early embryonic development. Rada-Iglesias called these regions class-2 elements.

Wysocka and Rada-Iglesias used a software program called GREAT (for Genomic Regions Enrichment of Annotation Tools) developed in the laboratory of Stanford researcher Gill Bejerano, PhD, assistant professor of developmental biology and of computer science, to analyze the categories of genes the two classes of enhancers might be controlling. They confirmed that the class-1 enhancers regulate genes active in embryonic stem cells, while the class-2 enhancers are associated with genes involved in processes such as gastrulation and the formation of germ layers — events that occur very early in development.

"When we compared the expression of the genes controlled by class-1 and class-2 elements, we found that the class-1 genes were active, as you would expect in human embryonic stem cells, and the class-2 genes were inactive," said Wysocka.

When the researchers triggered the differentiation of the embryonic stem cells into a cell type called neuroectoderm, however, about 200 of the class-2 enhancers began to display a class-1, or activated, signature, and their associated genes were turned on. The researchers expect that specific sets of class-2 elements are activated during the development of various tissue types during embryogenesis.

"These class-2 elements are clearly poised to orchestrate development in a cell-type-specific manner," said Wysocka.

Finally, the researchers attached individual enhancers to a reporter gene that would glow green when expressed. When they introduced the enhancer-reporter constructs into one-celled zebrafish embryos and allowed the embryos to develop, they saw a pattern of expression that was developmentally specific in location and timing and mimicked the expression of nearby developmental genes involved in normal fish embryogenesis.

"It's clear that these enhancers are becoming active at specific times during development," said Wysocka. "Now we have over 2,000 elements that can be used to study development and isolate transient cell populations."

In addition, Wysocka and Rada-Iglesias and their colleagues are now interested in identifying the mechanism that triggers the switch of the class-2 elements from an inactive to an active state, as well as how the poised state is initially set up at these elements in the embryonic stem cells.

INFORMATION:

In addition to Rada-Iglesias and Wysocka, other Stanford researchers involved in the work include postdoctoral scholars Ruchi Bajpai, PhD, and Samantha Brugmann, PhD; senior research scientist Tomek Swigut, PhD; and medical student Ryan Flynn.

The work was supported by the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, the W.M. Keck Foundation and the European Molecular Biology Organization. Information about Stanford's Departments of Developmental Biology and of Chemical and Systems Biology, which also supported the research, is available at http://devbio.stanford.edu/ and http://casb.stanford.edu/.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://mednews.stanford.edu. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Hospital & Clinics and Lucile Packard Children's Hospital. For information about all three, please visit http://stanfordmedicine.org/about/news.html.

Stanford study identifies multitude of genetic regions key to embryonic stem cell development

2010-12-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Feast, famine and the genetics of obesity: You can't have it both ways

2010-12-16

LA JOLLA, CA-In addition to fast food, desk jobs, and inertia, there is one more thing to blame for unwanted pounds-our genome, which has apparently not caught up with the fact that we no longer live in the Stone Age.

That is one conclusion drawn by researchers at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, who recently showed that mice lacking a gene regulating energy balance are protected from weight gain, even on a high fat diet. These findings have implications for the worldwide obesity epidemic and its consequences, such as type two diabetes.

In the December 16, ...

Software improves understanding of mobility problems

2010-12-16

The software tool presents data visually and this allows those without specialist training – both professionals and older people – to better understand and contribute to discussions about the mechanics of movement, known as biomechanics, when carrying out everyday activities.

The software takes motion capture data and muscle strength measurements from older people undertaking everyday activities. The software then generates a 3D animated human stick figure on which the biomechanical demands of the activities are represented visually at the joints. These demands, or stresses, ...

Insight offers new angle of attack on variety of brain tumors

2010-12-16

A newly published insight into the biology of many kinds of less-aggressive but still lethal brain tumors, or gliomas, opens up a wide array of possibilities for new therapies, according to scientists at Brown University and the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF). In paper published online Dec. 15 in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, they describe how a genetic mutation leads to an abnormal metabolic process in the tumors that could be targeted by drug makers.

"What this tells you is that there are some forms of tumors with a fundamentally altered ...

Novel therapy for metastatic kidney cancer developed at VCU Massey Cancer Center

2010-12-16

Richmond, Va. (Dec. 15, 2010) – Researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and the VCU Institute of Molecular Medicine (VIMM) have developed a novel virus-based gene therapy for renal cell carcinoma that has been shown to kill cancer cells not only at the primary tumor site but also in distant tumors not directly infected by the virus. Renal cell carcinoma is the most common form of kidney cancer in adults and currently there is no effective treatment for the disease once it has spread outside of the kidney.

The study, published in the journal ...

Close proximity leads to better science

2010-12-16

Absence makes your heart grow fonder, but close-quarters may boost your career.

According to new research by scientists at Harvard Medical School, the physical proximity of researchers, especially between the first and last author on published papers, strongly correlates with the impact of their work.

"Despite all of the profound advances in information technology, such as video conferencing, we found that physical proximity still matters for research productivity and impact," says Isaac Kohane, the Lawrence J. Henderson Professor of Pediatrics at Children's Hospital ...

Study links increased BPA exposure to reduced egg quality in women

2010-12-16

A small-scale University of California, San Francisco-led study has identified the first evidence in humans that exposure to bisphenol A (BPA) may compromise the quality of a woman's eggs retrieved for in vitro fertilization (IVF). As blood levels of BPA in the women studied doubled, the percentage of eggs that fertilized normally declined by 50 percent, according to the research team.

The chemical BPA, which makes plastic hard and clear, has been used in many consumer products such as reusable water bottles. It also is found in epoxy resins, which form a protective ...

Plasma therapy: An alternative to antibiotics?

2010-12-16

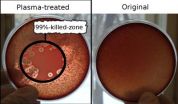

Cold plasma jets could be a safe, effective alternative to antibiotics to treat multi-drug resistant infections, says a study published this week in the January issue of the Journal of Medical Microbiology.

The team of Russian and German researchers showed that a ten-minute treatment with low-temperature plasma was not only able to kill drug-resistant bacteria causing wound infections in rats but also increased the rate of wound healing. The findings suggest that cold plasmas might be a promising method to treat chronic wound infections where other approaches fail.

The ...

MDMA: Empathogen or love potion?

2010-12-16

15 December 2010, MDMA or 'ecstasy' increases feelings of empathy and social connection. These 'empathogenic' effects suggest that MDMA might be useful to enhance the psychotherapy of people who struggle to feel connected to others, as may occur in association with autism, schizophrenia, or antisocial personality disorder.

However, these effects have been difficult to measure objectively, and there has been limited research in humans. Now, University of Chicago researchers, funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, are reporting their new findings in healthy volunteers ...

Sticking to dietary recommendations would save 33,000 lives a year in the UK

2010-12-16

If everyone in the UK ate their "five a day," and cut their dietary salt and unhealthy fat intake to recommended levels, 33,000 deaths could be prevented or delayed every year, reveals research published online in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health.

Eating five portions of fruit and vegetables a day accounts for almost half of these saved lives, the study shows. Recommended salt and fat intakes would need to be drastically reduced to achieve similar health benefits, say the authors.

The researchers base their findings on national data for the years 2005 ...

Doctors on Facebook risk compromising doctor-patient relationship

2010-12-16

Doctors with a profile on the social networking site Facebook may be compromising the doctor-patient relationship, because they don't deploy sufficient privacy settings, indicates research published online in the Journal of Medical Ethics.

The authors base their findings on a survey of the Facebook activities of 405 postgraduate trainee doctors (residents and fellows) at Rouen University Hospital in France. Half those sent the questionnaire returned it.

Almost three out of four respondents (73%) said they had a Facebook profile, with eight out of 10 saying they had ...