(Press-News.org) By offering a microscopic "tightrope" to cells, Virginia Tech and Johns Hopkins University researchers have brought new insights to the way migrating cells interact in the body. The researchers changed their testing environment for observing cell-cell interaction to more closely mirror the body, resulting in new observations of cells interacting like cars on a highway -- pairing up, speeding up, and passing one another.

Understanding the ways migrating cells react to one another is essential to predicting how cells change and evolve and how they react in applications, such as wound healing and drug delivery. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team formed by Mechanical Engineering Associate Professor Amrinder Nain, graduate researchers Jugroop Singh and Aldwin Pagulayan, and Johns Hopkins Assistant Professor Brian Camley, pivoted from traditional testing methods to more accurately observe how moving cells behave when they encounter one another.

Cells have polarity, a north-south orientation, like common magnets. Polarizing helps a cell orient itself correctly with other cells and also establish a leading and trailing edge - the front and the back ends of the cell in motion. As cells move and divide, their polarities change and shift, a product of the motion of molecules within them. Each cell's motion is controlled by protrusions - tentacles that pull each cell along at the leading edge, controlling its motion - and when migrating cells collide, they tend to repel one another, causing their protrusions to contract inward. Cells form new protrusions away from the collision to change direction and go to new places.

This behavior of changing direction after collisions is called contact inhibition of locomotion, and it brings about a change in the cell's poles. After a collision, the trailing edge becomes the leading edge, thus reversing the migration direction.

Since the 1950s, contact inhibition of locomotion has been observed by placing cells in a flat environment, such as a petri dish. This is unlike the setting of a body, however, where cells move along networks of fibers. To bring their observations closer to the natural environment, the team introduced cells onto a single fiber, a kind of cellular "tightrope." In that setting, they found that cell-cell interaction was entirely different than that of a flat surface. Whereas cells collide on a flat surface, they become far more civil when walking along a fiber. When sharing the tightrope, given nowhere to go, cells tended to move past one another.

Of course, a body is made of many fibers, not just one. To further investigate cellular behavior in its natural environment, the team introduced a second, parallel fiber. Cellular behavior changed again: instead of moving past one another, cells would stick together, moving in pairs with one of the cells changing its poles.

Another change occurred when cells divided. After a new cell was formed from a division, called a "daughter cell," they tended to walk past other cells more often in both configurations. The researchers found that daughter cells moved with increased speed, and this was likely a contributor to their ability to move past more often.

The team was able to recreate these behaviors with a simple model that assumed cells crawled along the fibers and reoriented when they came in contact with another cell's front, and that daughter cells moved faster.

"This cocktail of mechanical engineering, cell biology, physics, and computational modeling reveals cell behaviors not known before," said Nain. "Cells and their environments are complex and constantly changing. Our collaborative work adds a twist to the knowledge of contact inhibition of locomotion, first discovered in the 1950s."

According to Camley, knowing this information furthers understanding into why some drugs work differently in a test on a petri dish than in an animal. The difference in flat-surface behavior versus fiber provides insights that could mean the difference between a impacting a cell with a drug or missing it, given a more holistic view of cellular responses.

"Instead of changing our view about the underlying biology, this shows how physical changes in the cell's environment can alter cell-cell interactions," said Camley. "Scientists often want to figure out how drugs can alter cell-cell interactions -- our results show that it's important to study these in as natural an environment as possible because environment plays a huge role."

INFORMATION:

Scientists of Tomsk Polytechnic University jointly with colleagues from different countries have developed a new sensor with two layers of nanopores. In the conducted experiments, this sensor showed its efficiency as a sensor for one of the doping substances from chiral molecules. The research findings are published in Biosensors and Bioelectronics (IF: 10,257; Q1) academic journal.

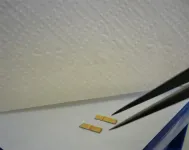

The material is a thick wafer with pores of 20-30 nm in diameter. The scientists grew a layer of metal-organic frameworks (MOF) from Zn ions and organic molecules on these thick wafers. The MOF has about 3 nm nanopores only. It plays the role of a trap for molecules, which must be detected.

"This sensor can operate with chiral molecules. Such substances consisting of chiral molecules are a lot among medical ...

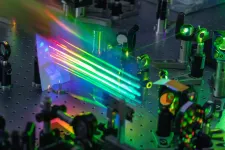

In the future, photovoltaic cells could be "worn" over clothes, placed on cars or even on beach umbrellas. These are just some of the possible developments from a study published in Nature Communications by researchers at the Physics Department of the Politecnico di Milano, working with colleagues at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg and Imperial College London.

The research includes among its authors the Institute of Photonics and Nanotechnology (IFN-CNR) researcher Franco V. A. Camargo and Professor Giulio Cerullo. It focused on photovoltaic cells made using flexible organic technology. Today's most popular photovoltaic cells, based on silicone technology, are rigid and ...

The Miscanthus genus of grasses, commonly used to add movement and texture to gardens, could quickly become the first choice for biofuel production. A new study shows these grasses can be grown in lower agricultural grade conditions - such as marginal land - due to their remarkable resilience and photosynthetic capacity at low temperatures.

Miscanthus is a promising biofuel thanks to its high biomass yield and low input requirements, which means it can adapt to a wide range of climate zones and land types. It is seen as a viable commercial option for farmers but yields ...

Energy models are used to explore different options for the development of energy systems in virtual "laboratories". Scientists have been using energy models to provide policy advice for years. As a new study shows, energy models influence policymaking around the energy transition. Similarly, policymakers influence the work of modellers. Greater transparency is needed to ensure that political considerations do not set the agenda for future research or determine its findings, the researchers demand.

Renewable energies bring many changes, including fluctuations in the energy supply and a more geographically distributed generation system. ...

A collaborative research project by team of undergraduate students from the University of Exeter's Natural Sciences department has been published in a prestigious academic journal.

Lewis Howell, Eleanor Osborne and Alice Franklin have had their second-year research published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry B.

Their paper, Pattern Recognition of Chemical Waves: Finding the Activation Energy of the Autocatalytic Step in the Belousov-Zhabotinsky Reaction, was a result of their extended experiment work in the Stage 2 module "Frontiers in Science 2".

Their project involved the Belousov-Zhabotinsky chemical reaction - an ...

March 7, 2021, KAUST, Saudi Arabia - KAUST Assistant Professor of Computer Science Mohamed Elhoseiny has developed, in collaboration with Stanford University, CA, and École Polytechnique (LIX), France, a large-scale dataset to train AI to reproduce human emotions when presented with artwork.

The resulting paper, "ArtEmis: Affective Language for Visual Art," will be presented at the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), the premier annual computer science conference, which will be held June 19-25, 2021.

Described as the "Affective Language for Visual Art," ArtEmis's user interface has seven emotional descriptions on average for each image, bringing the total count to over 439K emotional-explained attributions from humans on ...

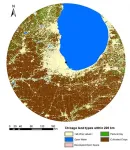

While urban agriculture can play a role in supporting food supply chains for many major American cities -- contributing to food diversity, sustainability and localizing food systems -- it is unrealistic to expect rooftop gardens, community plots and the like to provide the majority of nutrition for the population of a metropolis.

That's the conclusion of a team of researchers who analyzed the nutritional needs of the population of Chicago and calculated how much food could be produced in the city by maximizing urban agriculture, and how much crop land would be needed adjacent to the city to grow the rest. The study was the first to evaluate land required to meet ...

Scientists have shown that SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can infect specific cells in the salivary gland in the mouth. The study by researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, National Institutes of Health and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and their collaborators within the Human Cell Atlas Oral & Craniofacial Network, also discovered that live cells from the mouth were found in saliva, and that the virus was able to reproduce within these infected cells.

The study revealed that salivary gland cells could play a role in transmission ...

Göttingen, March 25, 2021. Testing and vaccination - these are the pillars on which humanity is trying to get a grip on the Coronavirus pandemic. Although it is taking longer than many had expected, it is believed that it is only a matter of time before we are all vaccinated and thus protected. However, time is also working for the virus, which has now mutated several times, with variants B.1.1.7 from the United Kingdom, B.1.351 from South Africa and P.1 from Brazil spreading rapidly. These viruses have mutations in the so-called spike protein, the structure on the surface of the virus that is responsible for attachment to host cells. At the same time, the spike protein is also the major target of the immune response. Antibodies generated in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination ...

Supersized alcopops are ready-to-drink flavored alcoholic beverages with high alcohol content that are disproportionately consumed by underage drinkers. There can be up to 5.5 standard alcoholic drinks in a single 24 ounce can, so consuming only one can of supersized alcopop is considered binge drinking, and consuming two cans can cause alcohol poisoning. Still, these products remain under-regulated and are available inexpensively at gas stations and convenience stores, where they are more readily accessible by underage youth.

New research led by George Mason University's College of Health and Human Services found that nearly ...