In only the second published study of prime editing's use in a mouse model, Medical College of Georgia scientists report prime editing and traditional CRISPR both successfully shut down a gene involved in the differentiation of smooth muscle cells, which help give strength and movement to organs and blood vessels.

However, prime editing snips only a single strand of the double-stranded DNA. CRISPR makes double-strand cuts, which can be lethal to cells, and produces unintended edits at both the work site as well as randomly across the genome, says Dr. Joseph Miano, genome editor, molecular biologist and J. Harold Harrison, MD, Distinguished University Chair in Vascular Biology at the MCG Vascular Biology Center.

"It's actually less complicated and more precise than traditional CRISPR," Miano says of prime editing, which literally has fewer components than the game-changing gene-editing tool CRISPR.

Miano was among the first wave of scientists to use CRISPR to alter the mouse genome in 2013. Two scientists were awarded the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the now 9-year-old CRISPR, which enabled rapid development of animal models, as well as the potential to cure genetic diseases like sickle cell, and potentially reduce the destruction caused by diseases like cancer, in which environmental and genetic factors are both at play.

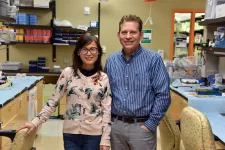

Prime editing is the latest gene-editing technology, and the MCG scientists report in the journal Genome Biology that they were able to use it to remove expression of a gene in smooth muscle tissue, illustrating prime editing's ability to create cell-specific knockout mice without extensive breeding efforts that may not result in an exact model, says Dr. Xiaochun Long, molecular biologist in the Vascular Biology Center. Miano and Long are corresponding authors of the new study.

Long, Miano and their colleagues did a comparative study using traditional CRISPR and prime editing in the gene Tspan2, or tetraspan-2, a protein found on the surface of cells. Long had earlier found Tspan2 was the most prominent protein in smooth muscle cell differentiation and was likely mutated in cardiovascular disease. She also had identified the regulatory region of this gene in cultured cells. However, it was unclear whether this regulatory region was important in mice.

They used CRISPR to create a subtle change in a snippet of DNA within the promoter region of Tspan2, in this case a three-base change, their standard approach to inactivating control regions of genes. DNA has four base pairs -- adenine, cytosine, guanine and thymine -- which pair up in endless different combinations to make us, and which gene-editing tools alter.

CRISPR created a double-strand break in the DNA and following the three-base change, the Tspan2 gene was no longer turned on in the aorta and bladder of mice.

They then used prime editing to make a single-strand break, or nick, and a single-base change -- like most of the gene mutations that occur in our body -- and found this subtle change also turned the Tspan2 gene off in the aorta and bladder, but without the collateral damage of CRISPR.

"We were trying to model what could happen with a single nucleotide change," says Miano. "We asked the question if we incorporate a single-base substitution, if we just make one base change, what happens to Tspan2 expression? The answer is it did the same thing as the traditional CRISPR editing: It killed the gene's expression."

But there were also important differences. Using CRISPR, they found evidence of significant "indels," short for insertions or deletions of bases in genes, which were unintended, both near the site where the intended edit was made and elsewhere.

The published paper includes a chart with numerous black bars illustrating where multiple nucleotides, the building blocks of DNA and RNA, are gone after using CRISPR. Indels are those unintended changes that genome editors strive to avoid because they can create deficits in gene expression and possible disease. With off-targeting, you could end up substituting one disease for another, Miano says.

But with prime editing, they saw essentially no indels either at the Tspan2 promoter region or elsewhere.

A Manhattan plot illustrated the off-targeting across all chromosomes using both techniques, with the CRISPR skyline stacking up like a real city while the prime editing skyline is comparatively flat.

"Prime editing is a less intrusive cut of the DNA. It's very clean," Miano says. "This is what we want: No detectable indels, no collateral damage. The bottom line is that unintended consequences are much less and it's actually less complicated to use."

Traditional CRISPR has three components, the molecular scissors, Cas9, the guide RNA that takes those scissors to the precise location on DNA and a repair template to fix the problem. Traditional CRISPR cuts both strands of the DNA, which also can happen in nature, can be catastrophic to the cell and must be quickly mended.

Prime editing has two arms, with a modified Cas9, called a Cas9 nickase, that will only make a single-strand cut. The scissors form a complex called the "prime editor" with a reverse transcriptase, an enzyme that can use an RNA template to produce a piece of DNA to replace the problematic piece in the case of a disease-causing mutation. PegRNA, or prime editing guide RNA, provides that RNA template, gets the prime editor where it needs to work and helps stabilize the DNA strands, which are used to being part of a couple.

During the repair of the nicked strand of targeted DNA, the prime editor "copies" a portion of the pegRNA containing the programmed edit, in this case a single-base substitution, so that the repaired strand will now carry the single base edit. In the case of creating a disease model, that enables scientists to "bias" the repair so the desired mutation is created, Miano says.

Dr. David Liu, chemical biologist, Richard Merkin Professor and director of the Merkin Institute of Transformative Technologies in Healthcare at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and his colleagues developed the first major gene editing technology to follow CRISPR. They reported on base editing technology in 2016, which uses "base editors" Liu described as "pencils, capable of directly rewriting one DNA letter into another by actually rearranging the atoms of one DNA base to instead become a different base." Liu and his postdoctoral fellow Dr. Andrew Anzalone, first reported on prime editing in the journal Nature in October 2019. Liu is a coauthor on the newly published study in Genome Biology on prime editing in mice.

Liu's original work on prime editing was done in culture, and others have shown its efficacy in plants. This is more proof of principle, Miano says.

The MCG scientists hope more of their colleagues will start using prime editing in their favorite genes to build experience and hasten movement toward its use in humans.

Their long-term goals including using safe, specific gene editing to correct genetic abnormalities during human development that are known to result in devastating malformations and disease like heart defects that require multiple major surgeries to correct.

Allison Yang, senior research assistant in the Miano lab, is preparing to use prime editing to do an in utero correction of the rare and lethal megacystis-microcolon-intestinal hypoperistalsis syndrome, which affects muscles of the bladder and intestines so you have difficulty moving food through the GI tract and emptying the bladder. In early work with CRISPR on vascular smooth muscle cells, Miano and colleagues inadvertently created a near-perfect mouse model of this human disease that can kill babies.

INFORMATION:

Collaborators on the new study include scientists from Albany Medical College, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Cornell University, Synthego, and Harvard University. The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Changes in just one DNA building block, or nucleotide, called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, are the most common type of genetic variation in people, according to MedlinePlus, and each person has millions in their genome. A tiny proportion of SNPs, like the one that causes sickle cell disease, occur in parts of the DNA that produce proteins, which determine cell function. However, the vast majority of SNPs, such as the artificial one generated with prime editing here, occur in the human genome where no protein-coding genes are found. This noncoding portion of the genome, the so called 'dark matter,' comprises 99% of our entire DNA blueprint of life. Noncoding parts of the genome include regulatory elements like the one controlling Tspan2 expression.

Read the full study.