Researchers reveal SARS-CoV-2 distribution and relation to tissue damage in patients

The first known study to measure SARS-CoV-2 viral load in a variety of organs and tissues may aid our understanding of how COVID-19 develops following infection

2021-03-30

(Press-News.org) Researchers have mapped the distribution of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in deceased patients with the disease, and shed new light on how viral load relates to tissue damage.

Their study of 11 autopsy cases, published today in eLife, may contribute to our understanding of how COVID-19 develops in the body following infection.

More than 24 million SARS-CoV-2 infections have been reported to date, and the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 has exceeded 828,000 worldwide. COVID-19 occurs with varying degrees of severity. While most patients have mild symptoms, some experience more severe symptoms and may need to be hospitalised. A minority of those in hospital may enter a critical condition, with respiratory failure, blood vessel complications, or multiple organ dysfunction.

"Clinical observations suggest that COVID-19 is a systemic disease, meaning that it affects the entire body rather than just a single organ such as the lungs," explains co-first author Stefanie Deinhardt-Emmer, Resident in Medical Microbiology, Jena University Hospital, Jena, Germany. "But we don't currently have a clear understanding of disease development in humans and other organisms, due to the lack of appropriate experimental models. Investigating the viral distribution of SARS-CoV-2 within the human body and how this relates to tissue damage would help us address this gap."

To do this, Deinhardt-Emmer and colleagues studied 11 autopsy cases of patients with COVID-19. They performed the autopsies at the early postmortem stage to minimise bias due to the degradation of tissues and viral ribonucleic acid (RNA - a molecule similar to DNA).

Their analysis revealed high viral loads in most of the patients' lungs, which had caused significant damage to those organs. Using an imaging technique called transmission electron microscopy, the team also visualised intact viral particles in the lung tissue.

"Interestingly, we also detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA throughout various other tissues and organs unrelated to the lungs that did not cause visible tissue damage," says co-first author Daniel Wittschieber, Senior Forensic Pathologist at Jena University Hospital. The researchers say that this distribution of viral RNA throughout the body supports the idea that our immune system is unable to respond adequately to the virus' presence in the blood.

"We show that COVID-19 is a systemic disease as determined by the presence of virus RNA, and yet unrelated to tissue damage outside the lungs," says co-senior author Bettina Löffler, Director of the Institute for Medical Microbiology, Jena University Hospital. "To our knowledge, this study is the only one to date that has measured viral loads in a wide variety of organs and tissues, with more than 60 samples studied per patient."

"The insights gathered from our work may add to our understanding of how COVID-19 develops in the body following infection," concludes co-senior author Gita Mall, Head of the Institute of Forensic Medicine, Jena University Hospital.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-30

Recent studies indicate a link between children's cardiorespiratory fitness and their school performance: the more athletic they are, the better their marks in the main subjects - French and mathematics. Similarly, cardiorespiratory fitness is known to benefit cognitive abilities, such as memory and attention. But what is the real influence of such fitness on school results? To answer this question, researchers at the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland tested pupils from eight Geneva schools. Their results, published in the journal Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise, show that there is an indirect link with cardiorespiratory fitness influencing ...

2021-03-30

Alloying, the process of mixing metals in different ratios, has been a known method for creating materials with enhanced properties for thousands of years, ever since copper and tin were combined to form the much harder bronze. Despite its age, this technology remains at the heart of modern electronics and optics industries. Semiconducting alloys, for instance, can be engineered to optimize a device's electrical, mechanical and optical properties.

Alloys of oxygen with group III elements, such as aluminum, gallium, and indium, are important semiconductor materials with vast applications ...

2021-03-30

It's no secret. Colorado's forests have had a tough time in recent years. While natural disturbances such as insect outbreaks and wildfires occurred historically and maintained forest health over time, multiple, simultaneous insect disturbances in the greater region over the past two decades have led to rapid changes in the state's forests.

A bird's eye view can reveal much about these changes. Annual aerial surveys conducted by the Colorado State Forest Service and USDA Forest Service have provided yearly snapshots for the state. New collaborative research led by Colorado State University and the University of Wisconsin-Madison now supplements this understanding with even greater spatial detail.

The ...

2021-03-30

A growing number of young people are identifying as part of the LGBTQ+ community, and many are challenging binaries in gender and sexual identity to reflect a broader spectrum of experience beyond man or woman and gay or straight. But not everyone is participating equally in these diverse forms of expression, according to new research from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Psychology Professor Phillip Hammack's latest paper, published in the Journal of Adolescent Research, is shedding light on the social factors that can either hinder or support expression of diversity in sexual and gender identity ...

2021-03-30

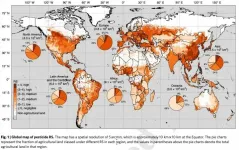

The study, published in Nature Geoscience, produced a global model mapping pollution risk caused by 92 chemicals commonly used in agricultural pesticides in 168 countries.

The study examined risk to soil, the atmosphere, and surface and ground water.

The map also revealed Asia houses the largest land areas at high risk of pollution, with China, Japan, Malaysia, and the Philippines at highest risk. Some of these areas are considered "food bowl" nations, feeding a large portion of the world's population.

University of Sydney Research Associate and the study's lead author, Dr Fiona Tang, said the widespread use of pesticides in agriculture - while boosting productivity - could have potential implications for the environment, human and animal ...

2021-03-30

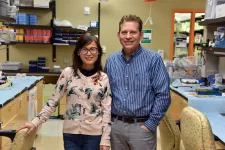

The latest gene editing technology, prime editing, expands the "genetic toolbox" for more precisely creating disease models and correcting genetic problems, scientists say.

In only the second published study of prime editing's use in a mouse model, Medical College of Georgia scientists report prime editing and traditional CRISPR both successfully shut down a gene involved in the differentiation of smooth muscle cells, which help give strength and movement to organs and blood vessels.

However, prime editing snips only a single strand of the double-stranded DNA. CRISPR makes double-strand cuts, which can be lethal to cells, and produces unintended edits at both the work site as well as randomly across the genome, ...

2021-03-30

HANOVER, N.H. - March 30, 2021 - Cyanobacteria living at the bottom of lakes may hold important, under-researched clues about the threat posed by these harmful organisms, according to a Dartmouth-led study.

The research, published in the Journal of Plankton Research, urges a more comprehensive approach to cyanobacteria studies in order to manage the dangerous blooms during a time of global climate change.

"Most studies of cyanobacteria focus on the times when they are visible in the water column," said Kathryn Cottingham, the Dartmouth Professor in the Arts and ...

2021-03-30

As our planet warms, seas rise and catastrophic weather events become more frequent, action on climate change has never been more important. But how do you convince people who still don't believe that humans contribute to the warming climate?

New UBC research may offer some insight, examining biases towards climate information and offering tools to overcome these and communicate climate change more effectively.

Researchers examined 44 studies conducted over the past five years on the attentional and perceptual biases of climate change - the tendency to pay special attention to or perceive particular aspects of climate change. They identified a number of ...

2021-03-30

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- A reproducibility crisis is ongoing in scientific research, where many studies may be difficult or impossible to replicate and thereby validate, especially when the study involves a very large sample size. For example, to evaluate the validity of a high-throughput genetic study's findings scientists must be able to replicate the study and achieve the same results. Now researchers at Penn State and the University of Minnesota have developed a statistical tool that can accurately estimate the replicability of a study, thus eliminating the need to duplicate the work and effectively ...

2021-03-30

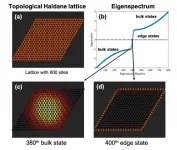

In a joint effort, researchers from the Humboldt-Universität (Berlin), the Max Born Institute (Berlin) and the University of Central Florida (USA), have revealed the necessary conditions for the robust transport of entangled states of two-photon light in photonic topological insulators, paving the way the towards noise-resistant transport of quantum information. The results have appeared in Nature Communications.

Originally discovered in condensed matter systems, topological insulators are two-dimensional materials that support scattering-free (uni-directional) transport along their edges, even in the presence of defects and disorder. In ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers reveal SARS-CoV-2 distribution and relation to tissue damage in patients

The first known study to measure SARS-CoV-2 viral load in a variety of organs and tissues may aid our understanding of how COVID-19 develops following infection