(Press-News.org) Scientists from Trinity College Dublin believe they have pinpointed our most distant animal relative in the tree of life and, in doing so, have resolved an ongoing debate. Their work finds strong evidence that sponges - not more complex comb jellies - were our most distant relatives.

Sponges are structurally simple, lacking complex traits such as a nervous system, muscles, and a though-gut. Logically, you would expect these complex traits to have emerged only once during animal evolution - after our lineage diverged from that of sponges - and then be retained in newly evolved creatures thereafter.

However, a debate has been raging ever since phylogenomic studies found evidence that our most distant animal relatives were in fact comb jellies. Comb jellies are considerably more complex than sponges, using a nervous system and muscles to detect and capture prey, for example, and a through-gut to help them digest it.

As such, if they were our most distant animal relatives, it would seem likely that the complex traits they evolved were later lost in simple animals such as sponges, or that they evolved twice over the course of evolutionary history - once in comb jellies and again, independently, in humans, sharks, flies and other related animals that have them.

Anthony Redmond, Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Trinity's School of Genetics and Microbiology, is first author of the research article just published in leading international journal, Nature Communications. He said:

"It may seem very unlikely that such complex traits could evolve twice, independently, but evolution doesn't always follow a simple path. For example, birds and bats are distantly related but have independently evolved wings for flight.

"However, instead of comb jellies, our improved analyses point to sponges as our most distant animal relatives, restoring the traditional, simpler hypothesis of animal evolution. This means both that the animal ancestor was simple and that muscles, and the nervous and digestive systems, although further elaborated upon in many lineages, have a single origin."

A new approach to making genetic comparisons

Comparing genomes to assess how species are related is a lot harder than it sounds. There are multiple different methods for doing so and different methods reach different conclusions - hence the disagreement as to whether sponges or comb jellies are our most distant relatives.

To resolve the debate, the Trinity team developed a new approach to analysing the amino acid sequences that make up an animal's proteins. Their approach reduced the errors associated with the all-important comparisons.

Natural selection to maintain the shape and function of proteins means that any given amino acid in a protein will usually only change to other amino acids with similar biochemical properties during evolution, e.g. like-for-like substitutions with respect to features such as positive/negative charge.

Failing to account for this can lead to errors when reconstructing phylogenetic relationships, which the Trinity researchers believe led to the recovery of comb jellies as our most distant animal relatives in some previous studies.

Aoife McLysaght, Professor of Genetics in Trinity's School of Genetics and Microbiology, and senior author of the research article, said:

"Our approach bridges the gap between two disagreeing methodologies, and provides strong evidence that sponges, and not comb jellies, are our most distant animal relatives. This means our last common animal ancestor was morphologically simple and suggests that repeated evolution and/or loss of complex features like a nervous system is less likely than if comb jellies were our most distant animal relatives.

"This is fascinating in its own regard, but it also represents an important step forward in phylogenomic research. Other researchers had come to different conclusions about our most distant animal relative, and that was the case even when they used the same data - they had just used different methods.

"Our new approach should be useful for similar studies in which scientists try to resolve how certain species are related to each other. This information is crucial to our understanding of evolution and can have important implications in other, related fields, such as biodiversity and conservation science."

INFORMATION:

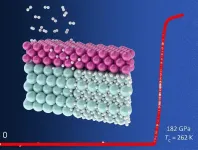

Superalloys that withstand extremely high temperatures could soon be tuned even more finely for specific properties such as mechanical strength, as a result of new findings published today.

A phenomenon related to the invar effect - which enables magnetic materials such as nickel-iron (Ni-Fe) alloys to keep from expanding with increasing temperature - was reported to have been discovered in paramagnetic, or weakly magnetized, high-temperature alloys.

Levente Vitos, Professor at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, says the breakthrough research, which includes a general theory explaining the new invar effect, promises to advance the design of high-temperature alloys with exceptional mechanical stability. The article was published in the Proceedings ...

The higher the number of plant and bird species in a region, the healthier the people who live there. This was found by a new study published in Landscape and Urban Planning and led by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv), the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre (SBiK-F) and the Christian Albrechts University (CAU) in Kiel. The researchers found that, in particular, mental health and higher species diversity are positively related, whereas a similar relationship between plant or bird species and physical health could not be proven.

The study led by researchers from iDiv, SBiK-F and CAU provides ...

University of Rochester researchers who demonstrated superconducting materials at room temperatures last fall, now report a new technique in the quest to also create the materials at lower pressures.

In a paper published in Physical Review Letters, the lab of Ranga Dias, assistant professor of mechanical engineering and of physics and astronomy, describes separating hydrogen atoms from yttrium with a thin film of palladium.

"This is a completely new technique that nobody has used before for high pressure superhydride synthesis," Dias says.

Hydrogen rich materials are critical in the ...

As with any complex machine, sometimes a simple crossed wire or short circuit can cause problems with how it functions. The same goes for our brains, and even when the short circuit is uncovered, sometimes experts don't have a quick fix.

A new study reveals that an evidence-based treatment may "fix" this human short circuit and, with the help of brain imaging, might predict treatment outcomes for adolescents with anxiety disorders. University of Cincinnati researchers say this could determine medication effectiveness more quickly to help patients.

Study results showed that brain imaging was able to predict -- after just two weeks of treatment ...

A targeted opioid that only treats diseased tissues and spares healthy tissues relieves pain from inflammatory bowel disease without causing side effects, according to new research published in the journal Gut.

The study, led by researchers at New York University College of Dentistry and Queen's University in Ontario, was conducted in mice with colitis, an inflammatory bowel disease marked by inflammation of the large intestine.

Opioids, which are used to treat chronic pain in people with inflammatory bowel disease, relieve pain by targeting opioid receptors, including the mu opioid receptor. When opioids activate the mu opioid receptor in healthy ...

A team from the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) and the CIBER Bioengineering, Biomaterials and Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN) has designed and tested, at a preclinical level, a new biomaterial for the treatment and recovery of muscle injuries. It is a boron-loaded alginate hydrogel, which would be administered with a subcutaneous injection. According to the tests carried out so far -in animal models-, it is capable of regenerating damaged muscle very rapidly -specifically, in half the time it takes for it to regenerate naturally.

The scientific advance could also be applied to the prevention and treatment of muscle atrophy associated with aging. The results of the work of these Spanish researchers have been published in the journal Materials Science & Engineering C.

The ...

Research led by Michigan Medicine's Scleroderma Program and published in Arthritis & Rheumatology found that tocilizumab, a FDA-approved anti-inflammatory drug used to combat rheumatoid arthritis, can prevent lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis if detected early enough in the disease course.

Systemic sclerosis is an autoimmune disease and the most serious form of scleroderma, the tightening and thickening of the skin. It can affect internal organs and lung disease is its leading cause of death, according to study author Dinesh Khanna, M.B.B.S., M.Sc., director of Michigan Medicine's Scleroderma Program.

"Some people have minimal lung disease; some people have life-threatening ...

A team of neurobiologists at the Institut de Neurosciences de la Timone (CNRS/Aix-Marseille Université) has just shown that within a population of rats it can predict which will become cocaine addicts. One of the criteria for addiction in rats is the compulsive search for a drug despite its negative consequences. Scientists observed abnormal activity in a specific region of the brain, the subthalamic nucleus, only in future addicted individuals, and did so before they were exposed to 'punishment' associated with the seeking for the drug. These results, which have just been published online by PNAS, also indicate that it is possible to reduce this compulsive cocaine-seeking behaviour in rats by stimulating the subthalamic nucleus, confirming its interest ...

Local alternative seafood networks (ASNs) in the United States and Canada, often considered niche segments, experienced unprecedented growth in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic while the broader seafood system faltered, highlighting the need for greater functional diversity in supply chains, according to a new international study led by the University of Maine.

The spike in demand reflected a temporary relocalization phenomenon that can occur during periods of systemic shock -- an inverse yet complementary relationship between global and local seafood systems that contributes to the resilience of regional food systems, according to the research team, which published its findings in Frontiers in Sustainable ...

WASHINGTON (March 31, 2021)-- New research published today in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives from Environmental Defense Fund and the George Washington University shows air pollution takes an enormous toll on health in the San Francisco Bay Area, and the impacts vary dramatically within neighborhoods. The magnitude of the health burden from pollution demonstrates the need for urgent action to cut air pollution and protect health, particularly in areas facing the highest impacts.

The analysis estimated that exposure to particle pollution (soot) resulted in more than 3,000 deaths and 5,500 new childhood asthma cases every year in the ...